Asia

China is moving towards implementing a national emissions trading system (ETS) after launching seven pilot carbon trading programs over the last few years. South Korea surpassed these combined pilots in China to become the second largest ETS in the world after the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) while Kazakhstan left the pilot phase behind and fully launched its mandatory cap-and-trade program.

COMPLIANCE MARKETS

China

In October 2011, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) designated seven provinces and cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guangdong, Hubei, and Shenzhen – as pilots to test an ETS. The final date for a national ETS has not been finalized, but it is anticipated that China will launch such a program sometime in 2016.

In June 2013, the city of Shenzhen, China became the first of the pilot programs to help pave the way for a national cap-and-trade program in China. Under the pilot program, 635 companies in Shenzhen, responsible for about 38% of the city’s emissions, face obligations to reduce their carbon intensity by about 6.7% on average per year by 2015. The first day of trading on the Shenzhen Emissions Rights Exchange saw eight transactions of emissions allowances completed for a total of 21,112 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). Allowance prices ranged from 28 to 32 yuan per tonne, close to the expected price of 30 yuan per tonne (US$4.89).

Emitters have the option of trading carbon offsets in the form of Chinese Certified Emission Reductions (CCERs) that are issued by the NDRC. The NDRC allows existing projects registered with the UN’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) to register as CCER projects – a source of potential relief for CDM suppliers reeling from the protracted collapse in prices for certified emissions reductions (CERs) and the recent ban on CERs from non-least developed countries for use in the EU ETS.

Beyond the historically strong relationship between suppliers of Chinese renewable energy offsets and European buyers, there is potential for CERs from China-based projects to fetch higher prices from domestic buyers should the pilots manage their prices well. With more than 70% of the world’s CERs issued in China as of the end of 2012, a big question on the minds of Chinese CER suppliers is how much domestic demand they can actually expect to absorb existing and new offset supply.

In March 2013, the NDRC released its first batch of 52 CCER methodologies eligible for domestic emissions trading, all of which are adapted from existing CDM methodologies. The list stays true to China’s traditional focus on renewable energy, energy efficiency and fuel switching, and methane. It also controversially includes methodologies for HFC-23 and N2O industrial gas offsets, which the EU ETS banned post-2012 in response to critiques of their environmental integrity.

The pilot municipalities are looking to expand the ETS programs, with Shenzhen planning to include transportation, Guangdong considering adding more industrial sectors and Hubei covering 49 new companies, according to a Carbon Pricing Watch 2015 brief. About 17 million allowances worth US$100 million had been traded in all pilot programs combined as of March 2015, according to the report.

Japan

Japan experimented with a domestic ETS as part of a low-carbon strategy that began in October 2008 and ended in 2012, according to Japan: An Emissions Trading Case Study. The experimental ETS consisted of two parts: the domestic ETS in which participating firms set their emissions reduction targets (absolute or intensity-based emissions targets) and had to surrender allowances and credits to comply and two offset crediting systems that provided credits to participant firms from the Domestic Credit system and the international Kyoto Protocol crediting mechanism.

However, the Japanese government declined to sign onto a second commitment period for the Kyoto Protocol at the international climate negotiations in 2010. In 2014, Japan announced it had abandoned its plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 25% below 1990 levels, and would instead aim to just keep its emissions from rising more than 3% above that year’s levels. It was a change driven largely by the country’s decision to shutter its nuclear power plants following the 2011 Fukushima disaster – a move that will lead to an increase in the use of fossil fuels.

Japan has since implemented the Bilateral Offset Crediting Scheme, which is now known as the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) and is designed to help the country reach its 2020 emissions reduction target at least cost and to develop export markets for low-carbon technology, products, and services, according to the case study. The mechanism allows Japanese firms to invest in emission reduction projects and programs in developing countries to earn offsets. The first bilateral agreement was signed with Mongolia in January 2013 and the first project was registered in Indonesia in October 2014. To date, 12 countries have signed bilateral documents: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kenya, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic , Maldives, Mexico, Mongolia, Palau, and Vietnam, according to the case study.

The Tokyo metropolitan area launched its own mandatory cap-and-trade system in 2010. The Tokyo ETS covers 40% of the industrial and commercial sectors’ carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which equates to 20% of all of Tokyo’s CO2 emissions, according to Tokyo: An Emissions Trading Case Study. The ETS covers both indirect and direct CO2 emissions from the use of energy (electricity, city gas, heavy oil, heat, and other energy). Covered entities include office buildings, commercial buildings, public facilities, district cooling/heating plants, factories, water and sewage facilities, and other facilities. As of January 9, 2015, 1,232 facilities had reporting obligations under the ETS, according to the case study.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has pledged to reduce emissions by 7% below 1990 levels by 2020 and by 15%, or 39 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), below 1992 levels by 2025. In the long term, Kazakhstan’s domestic goal is 25%, or 65 MtCO2e, below 1992 levels by 2050. Its ETS will contribute to achieving those emissions reduction goals.

Kazakhstan fully launched its mandatory ETS covering CO2 emissions in 2014 after a Phase I pilot in 2013, with Phase II taking place over the 2014-2015 timeframe and Phase III occurring in 2016-2020. During Phase I, the Kazakh ETS imposed allowance surrender obligations on 178 companies, and the cap for these companies was 147 MtCO2e. The cap covers 55% of the nation’s total GHG output, and 77% of the country’s CO2 emissions, according to Kazakhstan: An Emissions Trading Case Study. The threshold for a company’s inclusion in the ETS is 20,000 tCO2e per year.

Phase II currently covers 166 entities from the following sectors: power and heat production, coal mining, oil and gas extraction, chemical industry, metallurgy (utilization of mine methane), the cement industry, and other processing industries. The only gas covered in Phase I and II is CO2, with other gases possibly included at a later phase, according to the case study.

Trading has been limited to date, with only 35 transactions representing a total of 1.3 MtCO2e, at an average allowance price of KZT406 (US$2) per tonne, according to the carbon pricing brief.

Domestic offsets located in Kazakhstan can stem from the following sectors: mining and metallurgy; agriculture; housing and communal services; forestry; prevention of land degradation; renewables; processing of municipal and industrial waste; transport; and energy-efficient construction. Other sectors or project types can be introduced over time, according to the case study.

South Korea

South Korea is home to the second largest carbon market in the world after the EU ETS after launching in January 2015. The program mainly affects the country’s largest corporations, with 10 companies responsible for an estimated 76% of emissions covered under the ETS.

Only four allowance trades have occurred as of May 2015 at a volume of 1,380 tonnes since businesses regulated by the cap-and-trade program have resisted complying with the regulation. Several entities have sued the government over the allocation of permits in an effort to increase the total amount of allocations. Emitters allege the government has under-allocated by up to 20%, but so far government officials have remained unmoved.

Sungwoo Kim, an official advisor to the government through consulting firm KPMG, has estimated there will be a 57 MtCO2e shortage during the first phase of the ETS (2015-2017), which could increase the costs for covered entities to meet their requirements. Compliance entities could fill the allocation gap by offsetting up to 10% of their emissions reductions. However, while offsets have transacted at higher volumes – five transactions totaling 279,658 tonnes as of May 2015 – than allowances, analysts warn that offsets are in short supply as the compliance market only allows for the use of domestic offsets.

The Ministry of Environment began issuing Korean domestic offset units (KOCs) from pre-existing Certified Emissions Reductions (CER) offsets in April 2015, meaning questions remain about the size and scope of offsets to be issued. So far, the ministry has converted around 1.9 million CERs. A total of 91 domestic CDM projects might be converted to provide 42 MtCO2e, according to Kim. But analysts at research firm Point Carbon estimate only 20 million offsets could make the cut (excluding HFC 23 and N20 offset project types that the EU ETS has ruled problematic and excluded from its program).

This potential shortage could change in Phase III of the ETS (2021-2025), when up to 50% of total offsets allowed may be international in origin.

China’s Carbon Emissions Traders Await Offset Demand (Ecosystem Marketplace)

Japan: An Emissions Trading Case Study (IETA)

Kazakhstan: An Emissions Trading Case Study (IETA)

South Korea: An Emissions Trading Case Study (IETA)

Standoff Continues In South Korea’s New Carbon Markets (Ecosystem Marketplace)

Tokyo: An Emissions Trading Case Study (IETA)

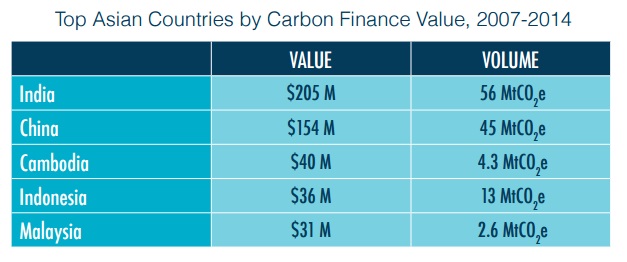

As in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), India and China have long served as a primary source of offset supply. The reason for this was closely tied to the compliance markets, since CDM project registration delays often led project developers to seek cash flow while waiting in line by certifying first to voluntary standards and selling to voluntary buyers. However, despite high volumes sold compared to other regions, the pile-up of unsold older vintages from Asia has caused prices to fall in recent years. Now, these renewable energy offsets must compete with other offsets in the region, notably forestry and household device distribution projects in Southeast Asia.

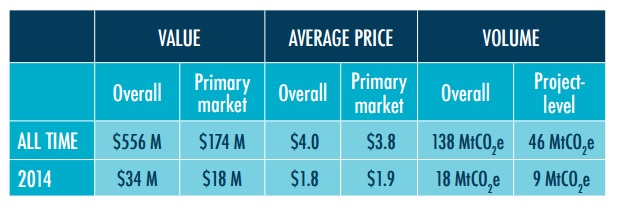

In fact, 2014 marked the first in which the largest supply country was not China or India, but Indonesia, which transacted 6 million tonnes (MtCO2e) in mostly forestry offsets but also some geothermal and landfill methane projects, according to Ecosystem Marketplace’s State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2015 report. India followed closely behind with 5.7 MtCO2e of predominantly wind offsets. Overall, Asia-based projects transacted 18 MtCO2e, a 16% drop compared to 2013. The price likewise declined 21%, to $1.9 per tonne in 2014.

Meanwhile, the volume of offsets transacted from projects in China fell, in part due to the country’s new pilot emissions trading systems (ETS). The seven jurisdictional pilots may provide an alternative for pre-CDM offsets that have languished in both the voluntary and compliance markets as many of those offsets are eligible to transition into domestic Chinese Certified Emissions Reductions (CCERs).

Currently about 99.5% of the estimated 15 million CCERs issued thus far are pre-CDM. However, four of the pilot systems (Beijing, Chongqing, Guangdong and Shanghai) have deemed those offsets ineligible for use, so it remains to be seen whether or not the other pilots will serve as a new source of demand. The province of Qingdao has announced it will start its own carbon market in 2015, followed by a nation-wide ETS scheduled to begin in 2016.

While a national Chinese ETS will dwarf other programs when it comes online, currently Korea’s ETS, launched in January of 2015, is the largest in Asia. While the Korean voluntary market experienced some transactions, compliance offsets have languished as companies have been slow to buy into the new market. Right now, the ETS only allows for the use of domestic offsets, which are in short supply.

Nearby Japan has only two compliance programs at the prefecture level – in Tokyo and Saitama – as well as a voluntary program in Kyoto. There used to be a country-wide voluntary carbon market experiment, but it ended in 2012. Now, outside of the government, 55 Japanese member industries and associations are committed to reducing emissions between 2013-2020 through the Keidanren’s Commitment to a Low Carbon Society, the largest Japanese economic association – and they do so in part by offsetting. Companies can offset voluntarily through the J-Credit Scheme, and label their products, services, and events as either offset or carbon neutral through the Japan Carbon Offsetting Scheme.

Related links

Ahead of the Curve: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2015 (Ecosystem Marketplace)