Keys To Launching Successful Forest Landscape Restoration

Forest restoration has the potential to bring millions of hectares of land back to life—a move that could help protect watersheds and ensure food security. The World Resources Institute (WRI) and the IUCN are hoping their global assessment of landscape restoration projects will spur further action.

Forest restoration has the potential to bring millions of hectares of land back to life—a move that could help protect watersheds and ensure food security. The World Resources Institute (WRI) and the IUCN are hoping their global assessment of landscape restoration projects will spur further action.

This article originally appeared on the World Resources Institute website. Click here to read the original.

17 February 2014 | In 2011, WRI, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and research partners published Landscapes of Opportunity, the first global assessment of where forest landscape restoration might be possible. This map helped build momentum toward the Bonn Challenge, a global commitment to start restoring 150 million hectares—an area three times the size of Spain—of lost and degraded forests by 2020.

Since then, several nations―ranging from the United States to Rwanda―have made Bonn Challenge restoration pledges, with pledges from others on the way. What some nations are asking now isn’t “what” restoration is or “where” it is possible, but “how” can it be done successfully?

To help answer this question, WRI and IUCN assessed more than 20 examples from around the globe of forest landscape restoration over the past 150 years, including both relative successes and failures. Examples came from countries such as Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Niger, Panama, Puerto Rico, South Korea, Sweden, Tanzania, and the United States. Lessons from these countries can not only provide insights into what works, but also inspire others to restore.

Forest Landscape Restoration in Action

History tells us that large-scale forest landscape restoration is possible.

Costa Rica witnessed its tropical forest cover decline from 85 percent of its land area at the start of the 20th century to below 30 percent by 1987. Yet through a series of restoration efforts—such as innovative financing approaches, policy reforms, and technical assistance to landowners—the nation’s forest cover climbed back to about 50 percent by 2010. This significant restoration yielded a variety of benefits—such as more forest products, ecotourism, and reduced soil erosion—for the nation’s environment, economy, and citizens.

South Korea restored its forests on a large scale after the Korean War. Between 1953 and 2007, forest cover expanded from 35 percent to 64 percent of the country’s total area, while its population doubled and its economy grew 300-fold. Those who say a country can’t grow its economy and restore its forests at the same time haven’t been to South Korea.

Costa Rica and South Korea are not alone. In the eastern United States, about 13 million hectares of forests recovered between 1910 and 1960. Puerto Rico’s forest cover climbed from 6 percent of the island around 1940 to about 40 percent in 2000. And farmers in southern Niger have miraculously restored 5 million hectares of agroforestry landscapes, improving their livelihoods and helping to reverse desertification.

These countries and others show that forest landscape restoration not only can be done, but can also deliver significant benefits to people and the planet.

WRI identified 2 billion hectares of degraded land that offer opportunities for restoration. Click on the map to view a larger version.

Lessons from the Past

So how can countries effectively pursue forest landscape restoration? Three lessons are emerging from our assessment.

First, countries with successful restoration programs were motivated by a wide variety of benefits, including improved water quality, soil retention, increased wood supplies, and job creation. More recently, the focus has expanded to recreation, wildlife and biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation benefits.

Second, the desired benefits can change over time. Forest landscape restoration in the southern United States, for example, was driven in the 1920s by a desire to protect watersheds, reduce soil erosion, and restore wood supplies. Later, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, it became a way to restore jobs. In the 1960s, recreation emerged as a priority. And in the decades that followed, wildlife conservation and climate change mitigation became aspirations.

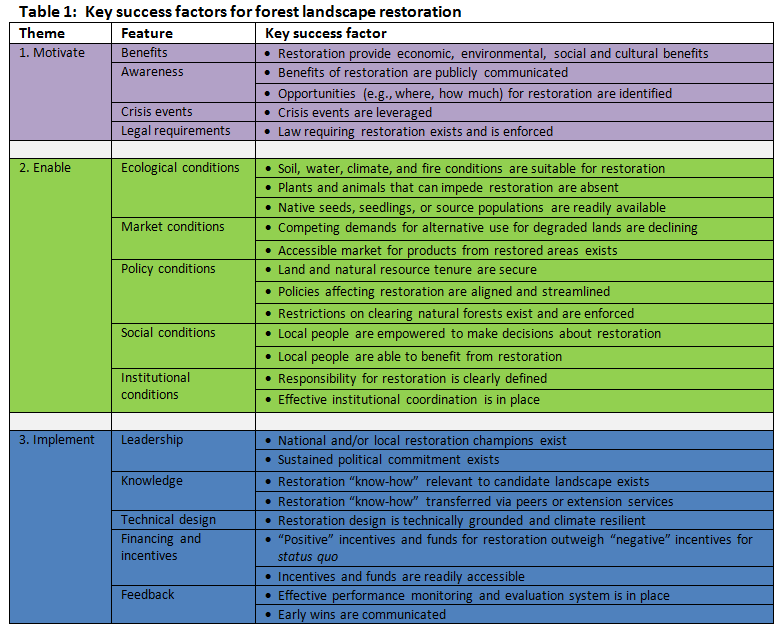

Third, we identified three common themes to successful restoration (Table 1):

- A clear motivation. Decision-makers, landowners, and/or citizens were inspired or motivated to restore forests and trees on landscapes.

- Enabling conditions in place. These included ecological, market, policy, social, and institutional conditions.

- Implementation capacity and resources. Capacity and resources were in place and mobilized to implement restoration on a sustained basis.

Different factors were important in different case studies, suggesting that context is important. No one factor appears to be sufficient to trigger restoration success; a combination was typically needed. And the success factors are inter-related. For instance, performance monitoring can help people adjust their implementation strategies, as well as further motivate restoration by publicizing successes and benefits. Finally, the greater the number of success factors that are in place, the greater the likelihood of successful restoration.

Emerging Tools to Support Future Restoration Efforts

Building on this assessment, WRI and IUCN will be publishing a “Rapid Restoration Diagnostic” that helps identify which success factors already exist and which are currently missing within landscapes being considered for restoration. It is designed to help decision-makers identify factors that must be addressed before investing large amounts of human, financial, or political capital in restoration.

The diagnostic tool will be complemented by an IUCN and WRI handbook to help decision-makers and communities plan and implement on-the-ground forest and landscape restoration. Both are slated to be released in 2014.

In the past, forests have too often been sacrificed in the name of economic development. In the future, we envision forest landscape restoration as an integral part of economic development, providing jobs for rural communities and generating a multitude of renewable goods and services.

History tells us that large-scale forest landscape restoration has been done before. We believe it can be done again.

Let the restoration generation begin!

- LEARN MORE: Check out WRI’s Forest and Landscape Restoration initiative

Stewart Maginnis is head of IUCN’s Forest Conservation Programme. Craig Hanson is the Director of WRI’s People and Ecosystems Program. He can be reached at [email protected].

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.