Why Are 11 US States Suing The EPA And Army Corps Over Water Quality?

Last week, New York Attorney General Eric Scheiderman filed suit against the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers to block the Trump administration’s suspension of guidance on clean water. In this three-part series, we examine the convoluted history of water regulation in the United States

First in a five-part-part series. Click here for part two.

13 February 2018 | By all accounts, John Rapanos thought it was absurd.

After all, those 50 or so muddy acres weren’t a true swamp or bog.

Hell, they were dry for much of the year.

How could they be a “wetland” – let alone “navigable waters”?

But that’s what Glenn Goff, the consultant Rapanos had hired, was telling him: that more than one-quarter of the 175 acres Rapanos wanted to sell for development were “forested wetlands” that were part of the “navigable waters of the United States” because they emptied into a hundred-year-old drainage system that emptied into the Hoppler Creek which emptied into the Kawkawlin River.

Under the Clean Water Act (CWA), the consultant said, Rapanos would need to get permission from the Army Corps of Engineers before filling those acres with gravel and sand.

Instead of applying for permission, however, Rapanos ordered the survey destroyed and began filling the wetland – sparking an 18-year court battle that culminated, in 2006, with an infamous US Supreme Court decision that yielded two “concurrent” but incompatible opinions on what constitutes “the waters of the United States”, or waters that the federal government is obligated to protect under the CWA.

A Tale of Two Opinions

One opinion, from Justice Anthony Kennedy, drew on centuries of laws, science and precedent to conclude that waters of the United States are those that have a “significant nexus” to waters that are “navigable in fact” (as opposed to merely “navigable”).

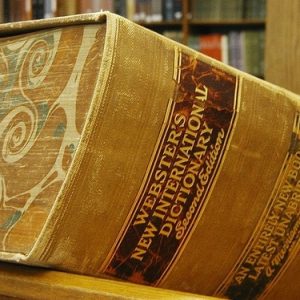

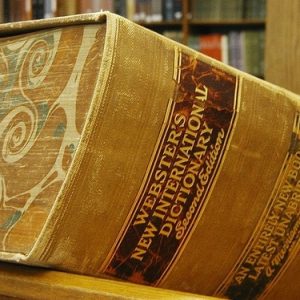

The other opinion, from Justice Antonin Scalia, threw centuries of science and precedent to the wind and drew instead on the literal definition of “waters” as found in the Second Edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary.

Scalia concluded that waters of the United States are limited to “streams[,] . . . oceans, rivers, [and] lakes” – a definition that excluded 98 percent of the continent’s waterways and meant that anyone could dig up wetlands (which he dismissed as “puddles”), dredge them, or fill them without regard for downstream consequences – which is exactly what people used to do in the bad old days of burning rivers and bubbly creeks.

“Lower courts and regulated entities will now have to feel their way on a case-by-case basis,” predicted then new Chief Justice John Roberts – and he was right. Although the Environmental Protection Agency scrambled to create post-Rapanos guidance for determining what was and what was not part of “the waters of the United States” under the CWA, developers and regulators increasingly found themselves turning to the courts.

Most courts, it turns out, followed the Kennedy definition, with some following both, and in 2015 the Obama administration issued 75 pages of guidance called the “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) rule, designed to fix the mess.

WOTUS came after seven months of public consultation, and it drew on over a million public comments and a thousand peer-reviewed papers. It was certainly detailed, but many said it was overly prescriptive, and was itself challenged in the courts.

That’s where it was when Donald Trump won the presidential election in 2016 and announced his intent to scrap Obama’s rule and make the long-ignored Scalia decision the law of the land.

So, here we are – coincidentally two years to the week after the deaths of both Scalia and Rapanos, who died three days apart from each other, on February 11 and 14, 2016 – and Rapanos vs United States is in the news again, hanging over the rivers, streams, bogs, swamps, and lakes of America like the fictional case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce hung over the poor souls of Charles Dickens’s “Bleak House”.

“Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on,” wrote Dickens about the fictional case – which emerged because one person left more than one will.

“Scores of persons have deliriously found themselves made parties in Jarndyce and Jarndyce without knowing how or why… Whole families have inherited legendary hatreds with the suit.”

More on the Bionic Planet Podcast

This story is accompanied by a two-part series on the Bionic Planet podcast, beginning with Episode 42. Bionic Planet is available on all podcatchers, including RadioPublic, iTunes, Stitcher, and on this device here:

The New Suit

Last week, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman opened the latest chapter in the saga of Rapanos vs United States, when he filed a suit against the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers, both of which are answerable to the President, on behalf of 11 individual states to block the Trump administration’s plan to delay, repeal, and replace WOTUS (also called “The Clean Water Rule”).

At stake is the protection of 274 million acres of wetland ecosystem spread across the United States – wetlands from which many of the country’s rivers, streams, and lakes emerge, and on which their cleanliness and consistency depend.

Under the CWA, “protection” rarely means “prohibition” of development – it usually means “permitting”, because real estate developers contemplating projects that impact “navigable waters” must first get permission from either the Army Corps of Engineers or a state or tribal agency acting on its behalf. To get that permission, developers have to keep damage to a minimum and then more than make up for any damage they do cause by restoring wetlands of equal or greater hydrologic value.

As a result, only 5 percent of permit requests are denied, while permitting contributes to a 25 billion restoration economy that employs more than 220,000 people.

To understand the permitting system (and the current legal morass), you need to know a bit about wetlands – and the Magna Carta.

Story continues below

Wetlands of the United States

Wetlands are bogs, swamps, and other patches of land that filter water and regulate floods – activities we now call “ecosystem services” that provide clean and reliable flows of water into rivers, lakes, and streams.

As Rapanos found, however, they aren’t always wet to the touch, but they’re usually too soggy for farming and were categorized as “wastelands” until the late 1800s, according to University of Colorado Biologist William Lewis’s 2001 book “Wetlands Explained”. He traces the regulation of wetlands back to the Swampland Act of 1850, which actively encouraged the draining of bogs, swamps, and muddy land to make way for farms – which often caused neighboring properties to flood while accelerating and contaminating downstream rivers.

Then came the invention of the double-barrel shotgun and the emergence of duck hunting.

“The first significant change was the awareness of duck hunters,” he said in an interview with Ecosystem Marketplace, which will appear in episode 31 of the Bionic Planet podcast, which I’ll post after wrapping up this series.

“They noticed that, despite the control of the federal government over the harvesting of ducks, the numbers of ducks were declining drastically, even within the lifetime of an individual hunter,” says Lewis. “They guessed, based on their knowledge of the landscape where the ducks were coming from, that the habitat of ducks was being destroyed to such an extent that it was reflected in what they were seeing on the flyways.”

That led to the creation of the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Duck Stamp program, which to this day uses proceeds from hunting licenses to support duck habitat – making Duck Stamps an early form of payment for ecosystem services (PES) and a precursor to the ecological restoration industry that we’ll be exploring in part four of this series.

The Commerce Clause

Federal regulation of waters comes from the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution, and the laws often references “navigable waters” – a term that lawmakers originally used the way the rest of us do: to describe rivers, lakes, streams, and other water bodies that are used for shipping and transport. Over time, as the understanding of water flows deepened, the term expanded to include tributaries like creeks and eventually wetlands – much to the consternation of some.

“It is sometimes said in the West, where the broadened concept of navigability reaches the outer limits of imagination, that navigable waters are those capable of floating a matchstick,” writes Lewis.

But the phraseology makes sense when placed in historical context, as William Sapp et al do in “From the Fields of Runnymede to the Waters of the United States: A Historical Review of the Clean Water Act and the Term ‘Navigable Waters’”, a 2006 piece that ran in the Environmental Law Reporter and is worth reading in its entirety.

Sapp traces the germination of the “waters of the United States” back 800 years, to the Magna Carta, which took control of waterways from the King and gave it to the people. Something similar happened in Continental Europe, where commoners, with the help of foreign powers, wrestled control of waterways like the Rhine away from the kleptocrats who built those lovely castles we see along the river.

Navigation rights were already a public good when the original 13 Colonies put the “united” into United States, in large part to unify rules around commerce.

“One of the primary reasons that the states sought the move from the Articles of Confederation and its loose-knit government to a more centralized union under the Constitution was so that interstate trade and traffic moving on land or by water would be subject to federal, rather than state, regulation,” writes Sapp.

From the very start, he says, water was the circulatory system of commerce, and all commerce depended on clean, regular flows of water – for transportation, for drinking, for watering crops, and eventually even for turning the turbines of industry. Unfortunately, rivers and streams have a tendency to disrespect state lines, and upstream states had a tendency to dump stuff into waters that went downstream, to people far, far away – a fact that led to ever more regulation of upstream activities.

As the scientific understanding of water-systems sharpened and evolved, so did regulation, and the article documents 250 years of evolution as we first added man-made canals to the water system and then came to understand the way water moves through nature – above the ground, through the ground and over the ground in the form of clouds and rain.

In the early days, they talked about “navigable waters of the united states”, which gradually split into several terms: “navigable waters”, “waters of the United States,” and “tributary of any navigable water.”

The Clean Water Act

During World War II, water quality took a back seat to the war machine, but with peacetime came the Water Pollution Control Act – a federal law that encouraged but didn’t require individual states to clean up their waters. The law proved inadequate, and water quality continued to degrade. By the 1960s, when Ohio’s Cuyahoga River literally erupted into flames – for at least the 13th time – people were sick of it, and Congress was listening.

By 1972, Congress had completely rewritten the Water Pollution Control Act and replaced it with the Clean Water Act, which President Richard Nixon promptly vetoed.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.