Waters Of The United StatesPart Two: Wetlands In The Clean Water Act

Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972, but it was slowly amended and refined. By 2000, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Environmental Protection Agency had settled on clear definitions of what constitutes “waters of the United States”. Not everyone, however, agreed with them.

Second in a five-part series. For part one, click here

15 February 2018 | In 1969, Ohio’s oil-laden Cuyahoga River burst into flames.

Many of us who were children then remember it like it was yesterday.

A river – a flowing body of water – caught fire???

A flowing body of the stuff we spray on fire to kill it… became fire?

What our half-formed brains (and many fully-formed ones) didn’t realize is that this was neither the first nor the worst time the Cuyahoga had burst into flames. It was the 13th conflagration in 100 years, and earlier episodes had killed people or raged for days, decimating miles of riverfront property and costing millions of dollars in damage.

But this was the the late 1960s, and people were sick of it: sick of burning rivers, sick of dead lakes… sick of being sick.

By the end of the year, Congress had passed the National Environmental Policy Act, which led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. By 1972, they had completely rewritten the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, creating what came to be known as the Clean Water Act (CWA) – the first federal protection for those surface waters that fell under federal jurisdiction.

Story continues below

Keeping it Fluid

The 129-page Clean Water Act protects all “navigable waters”, which it merely describes as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.”

Lawmakers drafting the bill were careful not to define the terms further “based on the fear that any interpretation would be read narrowly,” according to the report that the House of Representatives sent along with the bill it sent to the Senate.

Rather than change the words they used, lawmakers changed the usage of the words, and they gave the implementing agencies leeway to do the same, within the bounds of reason and science.

“The [Public Works] Committee fully intends that the term ‘navigable waters’ be given the broadest possible constitutional interpretation unencumbered by agency determinations which have been made or may be made for administrative purposes,” the House report said – and with good reason, according to both University of Colorado Biologist William Lewis and legal scholar William Sapp, writing in “Wetlands Explained” and “From the Fields of Runnymede to the Waters of the United States”, respectively.

Both of them chronicle the debates lawmakers undertook while grappling with the challenge of protecting something that not only flows from US state to US state, but from physical state to physical state – from ice to liquid to vapor – as surface waters (as opposed to groundwater, which is protected differently) move over ground and through earth and air. In those less partisan days, a Senator like Ed Muskie of Maine was able to cite the latest research on “hydrologic cycles” without some James Inhofe-type character popping up with a snowball or water-bottle to “refute” him.

The overwhelming majority of lawmakers agreed to give the Army Corps and EPA room to administer the law as they saw fit, on the premise that these administering agencies held the expertise, and that courts would act as a backstop for any overreach. The Supreme Court would eventually rule that even courts should defer to administrative expertise, unless the agencies fail to explain their actions in a reasonable way or run afoul of something called the Administrative Procedures Act, which lays out procedures for creating and implementing rules like this.

Although often credited with delivering the Clean Water Act, President Richard Nixon derided it as “budget-wrecking” and vetoed it.

Both houses of Congress overrode the veto by wide margins, and with broad bipartisan support.

Wetlands – In or Out?

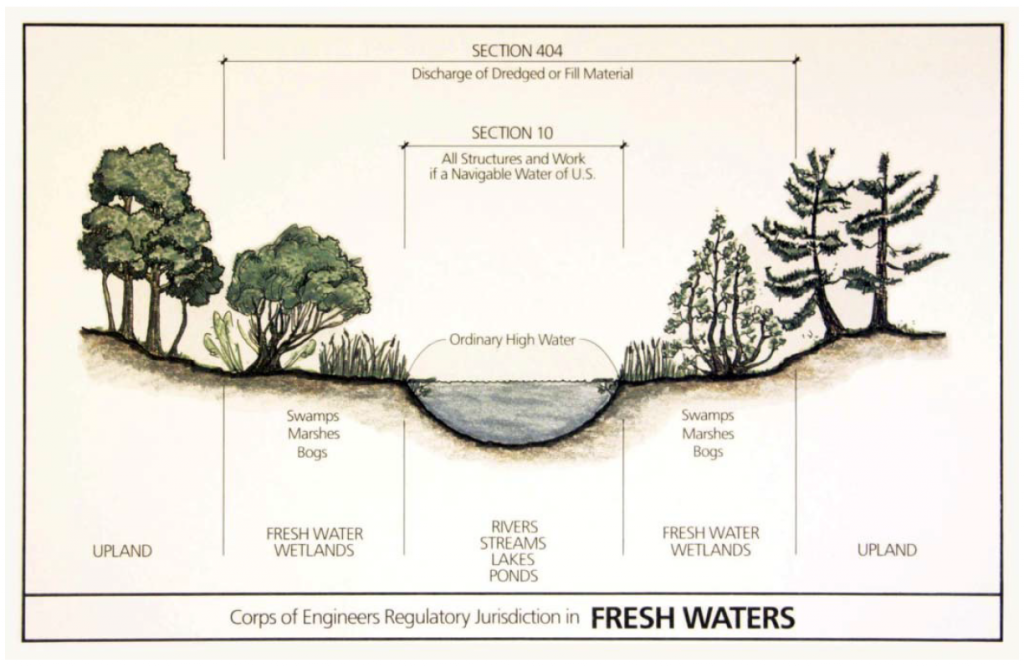

The new law didn’t ban pollution, dredging, or filling, but Section 404 did require real estate developers or anyone contemplating projects that impact “navigable waters” to first get permission from either the Army Corps of Engineers or a state or tribal agency acting on its behalf before breaking ground or dumping into the waters.

The Army Corps created a clear but cumbersome process for issuing permits, but wetlands were a point of contention from day one – and not because ravenous regulators were hungering to expand their turf.

“With the extension of the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction to wetlands, the Army Corps of Engineers became guardian of some 100-million acres of swamp, marsh, and bog in the contiguous states and another 170-million acres in Alaska,” writes Lewis. “Even though the Corps has never shown itself to be intimidated by any project of earthly proportions, the prospect of eternal vigilance and endless permitting on lands of such extent and dispersion must have been daunting.”

The Corps initially balked at being required to inspect and approve territory beyond its traditional purview of rivers, streams, and coastal areas – let alone so much of it – but the Natural Resources Defense Council sued, and the US District Court of Connecticut ruled that, in the context of the CWA, the term “navigable waters” was clearly “not limited to the traditional tests of navigability” as defined in the dictionary.

By 1977, wetlands were solidly in the law, and with bipartisan agreement.

“The once seemingly separate types of aquatic systems are, we now know, interrelated and interdependent” said Tennessee Republican Howard Baker. “We cannot expect to preserve the remaining qualities of our water resources without providing appropriate protection for the entire resource.”

In 1987, the EPA convened a group called the National Wetlands Policy Forum.

“The forum was diversely constituted,” writes Lewis. “It included individuals of both centrist and polar positions, and one product of the forum was a policy subsequently described as no net loss.”

Balancing Economy and Ecology

The concept of no net loss dovetailed with the permitting provisions in Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, where Congress tried to strike a balance between economy and ecology.

They acknowledged that cities would expand and contract, and there might be a time when it’s in most people’s interest to let a city build a road through a wetland, or let a developer dredge a stream for a new housing project, or even discharge pollutants into a river. In such circumstances, if local authorities green-light a project, it still has to ask the Army Corps of Engineers for permission to impact the waters of the United States, and that’s when the permitting process begins.

The process involves mandatory public consultation and is built on a “mitigation hierarchy” that also applies under the Endangered Species Act, where the Department of Fish and Wildlife oversees permitting for projects that impact sensitive habitat. Researchers recently reviewed 88,000 consultations under the ESA between 2008 and 2015 and found that no projects had been stopped or even changed in a major way to protect habitat, and earlier regional studies of wetland permitting show that 95 percent of all requests are granted.

The hierarchy says developers should first try to avoid damages, then minimize those they can’t avoid, and finally fix any areas they damage or restore similar areas of equal or greater value in the same watershed. The process was slow at first, as developers were forced to fix their own messes or restore degraded areas directly, but it sped up as entrepreneurial ecologists and landscape architects began proactively restoring degraded areas to create offsets for sale to developers, as we’ll see in part four of this series.

What is a Wetland?

In the 2006 Supreme Court case of Rapanos vs United States, Justice Antonin Scalia repeatedly dismissed the ecological value of wetlands, at one point exclaiming that “the only reason it’s a water of the United States is that there are some puddles on this land, right?”

In actual fact, the Army Corps created a detailed manual for identifying wetlands in 1987, and it built the guidance on the hydrologic properties associated with lands that filter water, regulate floods, and provide habitat.

“They came to define wetlands as…lands that have water closer than 12 inches to the surface for a duration of more than two weeks at a time, during the growing season, in most years,” says Lewis. “You can make a little list of those criteria, and if you had a hydrologic record you could make a certain identification of a certain area as a wetland or not.”

But long-term hydrologic records aren’t available for most lands, so the Corps turned to indicators.

“They look for hydric soils, which give evidence of being waterlogged, or vegetation – particularly long-lived vegetation like trees or long-lived shrubs – that are unique to wetlands,” says Lewis. “There are national lists of these things, and you identify the vegetation as either belonging to a wetland or not belonging to a wetland. It’s all been worked out in great detail.”

Some landowners, he says, would try to disguise the land by removing the vegetation, but the soils remained, and the land – though dry on the surface – was usually too waterlogged to support agriculture.

“The landowner who’s not farming might be frustrated and say, ‘Well, this is a piece of land that I want to develop, and I’ve been hears five years, and I haven’t seen any water on the surface,’” says Lewis. “In cases like that, they probably don’t want to know why it is we do that.”

Meanwhile, the agencies’s guidance on what constitutes “waters of the United States” was continuing to evolve, and in 1988 they settled on a definition that included “intrastate lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent streams), mudflats, sandflats, wetlands, sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa lakes, or natural ponds, the use, degradation or destruction of which could affect interstate or foreign commerce including any such waters [used for recreation, fishing, or industry].”

It was broad, but the underlying theme was some sort of connection to waters that were navigable in the dictionary sense. The Army Corps even extended the definition to isolated or man-made ponds that served as habitat for migratory birds – a definition that proved controversial from day one.

More on the Bionic Planet Podcast

This story is accompanied by a two-part series on the Bionic Planet podcast, beginning with Episode 42. Bionic Planet is available on all podcatchers, including RadioPublic, iTunes, Stitcher, and on this device here:

Enter John Rapanos

In 1988, Michigan real estate investor John Rapanos optioned 175 acres of land in Williams Township to a developer who wanted to build a shopping mall. Rapanos began clearing the land, and his lawyer filed the requisite paperwork with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) on December 2.

The DNR told him that the property seemed to have wetlands on it, but that Rapanos could continue developing those parts that were not wetland, but that he’d need permission from the Army Corps of Engineers to continue developing the parts that were. DNR inspectors visited the property on March 1, 1989, and wrote that “[t]he vegetation on much of the site had been scalped, removed by using either a bulldozer, or some other type of heavy equipment․”

By then, Rapanos had spent over $300 clearing the land, and he hired a wetlands consultant named Glenn Goff to survey the land and, according to Goff, ordered him to “get [the DNR] off my back.”

Goff concluded that roughly 50 acres were clearly wetlands, and he testified in court that Rapanos vowed to “destroy all those (expletive deleted) wetlands.”

By all accounts, he made good on his threat, and DNR inspector Charles Dodgers documented what he called “systematic wetlands destruction” over the coming months. The state issued the first of several cease-and-desist orders in July, but Rapanos’s attorneys argued that the federal law did not apply to him. So the state called in the federal EPA, which issued its own cease-and-desist order in 1991.

Rather than heed the warnings, Rapanos began clearing and filling two other wetlands that clearly drained into far-away rivers and streams – spending $158,000 to destroy 17 of 64 acres of wetland on one 275-acre property, and spending $463,000 to destroy 15 of 49 acres on a 200-acre site.

Eventually, the Department of Justice got involved, and Rapanos was found guilty of violating the Clean Water Act – a criminal offense. At Rapanos’s trial, Indiana University Professor Daniel Willard testified that all three wetlands eventually drained into rivers and streams, and they provided clear ecosystem services, including support for “habitat, sediment trapping, nutrient recycling, and flood peak diminution.”

“[G]enerally for all of the…sites we have a situation in which the flood water attenuation in that water is held on the site in the wetland…such that it does not add to flood peak,” he said. “By the same token it would have some additional water flowing into the rivers during the drier periods, thus, increasing low water flow.”

What’s more, all of the properties had surface connections to tributaries of “traditionally navigable” waters (also called “navigable-in-fact” waters), which are those you can sail a boat on. Specifically, one connected to a drain that flowed into a creek that flowed into the Kawkawlin River. Another connected to a drain that flowed into the Tittabawassee River. And the third flowed directly into the Pine River, which flows into Lake Huron.

Rapanos appealed – based primarily on his belief that the federal government had no jurisdiction on his land. The case spent years bouncing around the courts before being picked up pro bono by the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF), a libertarian law firm devoted to fighting what it perceives as federal overreach.

PLF attorney Reed Hopper dismissed the wetlands as “puddles”, but he primarily argued that they were too far away from “navigable-in-fact” waters to be considered “navigable waters”, and were thus not part of the waters of the United States.

The Significant Nexus Test

Rapanos wasn’t the only person who believed the Army Corps had pushed the envelope on its definition of what constituted navigable waters.

In 1992, three years after his battle began, the Corps denied the Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (SWANCC) permission to convert old quarries into waste dumps, arguing that the quarries had become isolated ponds akin to the naturally-occurring prairie potholes that dot the Great Plains and provide habitat for migratory birds. The old quarries’ new function as habitat, the Corps said, brought them under their protectorate.

That sparked a nine-year court battle that landed in the Supreme Court in 2001, resulting in a 5-4 ruling that the Army Corps’s “Migratory Bird Rule” was a step too far, and that even prairie potholes were outside its purview.

Migratory birds, they said, didn’t provide a “significant nexus” between isolated ponds and waters that were “navigable in fact”. Those ponds were, therefore, not “navigable” even under the evolving definition, and were therefore not part of the waters of the United States.

Meanwhile, John Rapanos’s court battle with US regulators was working its way up the system, and it reached the Supreme Court in 2006.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.

Jual

obat aborsi obat penggugur kandungan

ampuh 100% manjur obat cytotec asli cara menggugurkan kandungan secara alami

dan tuntas tanpa efek samping dan tidak mempengaruhi kehamilan berikut nya,

cocok bagi wanita yang ingin melakukan aborsi dengan kehamilan yang tidak di

inginkan contoh nya korban pemerkosaan,tuntutan kerja,dll….smoga lekas selelai

permasalah anda dengan ada nya layanan kami.

Apakah

Legal Bagi Saya Untuk Menggunakan Layanan Ini?

Kebanyakan negara memberikan izin untuk mengimpor obat dalam jumlah yang

kecil, untuk penggunaan pribadi, dan tidak untuk tujuan komersial.

Perempuan yang tinggal di negara dimana hak-hak perempuan tidak

terpenuhi dan aborsi masih dibatasi, mereka dapat mengatakan bahwa mereka

mengalami keguguran jika mereka memerlukan bantuan medis. Tanda-tanda aborsi

medis sangat mirip dengan keguguran spontan dan sangat sulit untuk dideteksi

apakah perempuan mengkonsumsi obat tertentu.

Aborsi medis pada usia awal kehamilan sangatlah aman dan efektif. Resiko

aborsi medis sangat jauh lebih rendah dibandingkan dengan resiko kehamilan dan

persalinan. Jutaan perempuan di seluruh dunia telah merasakan keberhasilan

penggunaan mifepristone dan misoprostol untuk aborsi awal kehamilan. Bahkan

obat-obat ini tidak memiliki efek jangka panjang bagi kesehatan perempuan.

Aborsi

Medis Memiliki Resiko Yang Kecil

Komplikasi serius pasca aborsi medis sangat jarang terjadi dan jikalau

terjadi dapat ditangani oleh dokter dengan penanganan kasus keguguran alami.

Kemungkinan komplikasi yang sebenarnya sangat jarang terjadi adalah adanya

pendarahan hebat (0.2%) , infeksi (kurang dari 1%) dan berlanjutnya kehamilan

(0,3% sampai usia kehamilan 9 minggu). Komplikasi ini dapat ditangani oleh

dokter dengan penanganan kasus keguguran alami. Hal ini dikarenakan kasus

keguguran alami terjadi sebanyak 15-20% dari semua kasus kehamilan dimana semua

dokter memahami bagaimana menangani kasus keguguran alami – atau aborsi medis

Aborsi

Medis Memiliki Efektivitas Yang Tinggi

Kombinasi antara Mifepristone dan misoprostol memiliki efektivitas yang

tinggi, aman, dan berterima. Aborsi yang komplit (dimana artinya perempuan

tidak perlu perawatan tambahan) dapat terjadi dengan kemungkinan 98% jika

kehamilan masih di bawah usia 9 minggu.

Kira-kira 2-5% perempuan menggunakan kombinasi mifepristone dan

misoprostol membutuhkan perawatan medis tambahan untuk menuntaskan aborsi tidak

komplit, menghentikan kehamilan yang berlanjut, atau mengontrol pendarahan.

Penggunaan misoprostol saja untuk penghentian kehamilan awal dapat

membantu aborsi hingga komplit sampai 84%.

Aborsi medis yang dilakukan pada awal kehamilan jauh lebih efektif dan

aman.

Apakah

Aborsi Saya Berhasil?

Mayoritas perempuan dapat mendeteksi apakah aborsinya berhasil atau

tidak segera setelah menggunakan obat, karena tanda-tanda kehamilan hilang

dengan cepat dan/atau beberapa perempuan mungkin melihat embrio atau kantung

kehamilan. Bahkan jika perempuan merasa ia sudah tidak lagi hamil, penting

untuk memasatikan apakah aborsi berhasil. Perempuan dapat melakukan USG setelah

aborsi medis atau melakukan testpack 3-4 minggu setelah aborsi.

Kapan

Saya Dapat Berhubungan Seks Lagi?

Untuk pencegahan infeksi, perempuan disarankan untuk menghindari

memasukkan benda apapun ke dalam vagina selama kurang lebih satu minggu setelah

aborsi medis.

Jika anda ngin membeli obat aborsi (obat penggugur kandungan) di

wilayah anda masing2 agar pesanan bisa langsung di terima anda bisa mengakseh

obat aborsi di kota besar ini. Jual obat aborsi semarang , jual obat aborsi malang , jual obat aborsi jakarta , jual obat aborsi depok , jual obat aborsi bekasi dan jual obat aborsi denpasar dll.

jual obat aborsi cikarang , jual obat aborsi surabaya , jual obat aborsi gresik , jual obat aborsi tangerang , jual obat aborsi lombok ,