Valuing the Arc: Five-Year Experiment Draws to a Close

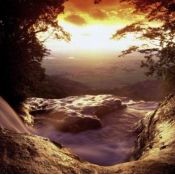

The downward flow of water from the Eastern Arc Mountains of Africa generates up to half of Tanzania’s power and provides much of Dar es Salaam’s drinking water. As agriculture moves up the slopes, however, it destroys the natural ecosystems that support the ancient catchments. A five-year effort to value those ecosystem services wraps up this month.

9 March 2012 | If anyone knows the value of the Eastern Arc Mountain ecosystem, it will be George Jambiya and Neil Burgess.

Together, they’ve spent more than three decades helping WWF and the Tanzanian government document thousands of rare plant and animal species that populate the Arc, not to mention the ecosystems they support and the animals and economies that depend on them.

Until now, however, neither can tell you with scientific certainty the value of the ecosystem services that flow from those plants and animals.

“On the one hand, you can say, ‘Look, we all depend on these services, so the value is inherent,'” says Burgess. “But we can’t go to Coca Cola and say, ‘This catchment delivers this amount of clean water, and has this value to you.'”

The ability to make that statement with confidence, however, would help save life-supporting ecosystem services that support – and, in our economic system, compete with – tangible hard commodities like timber and food.

“Right now, a lot of the values that are being applied to forestry management are only taking into account things like timber prices and logging permit values,” says Jambiya. “Things such as carbon sequestration and, especially, hydrological services don’t come into play, and the value of water is not determined by the market or even by supply and demand – but by an arbitrarily-set figure, which is probably very much on the low side. Often the official water fees are not paid, making the resource effectively free. The values of biodiversity are even worse in terms of valuing their market value.”

The two are among a handful of experts spearheading a five-year research and policy project called

“Valuing the Arc“, which wraps up this month. Its mission is to quantify the economic value of specific ecosystem services in the Eastern Arc Mountains, and it harvests expertise from five UK-based universities (Cambridge, East Anglia, York, Leeds, and Cranfield), two Tanzanian universities (University of Dar es Salaam and Sokoine University of Agriculture), the WWF Tanzania Programme Office, and the Natural Capital Project.

Along the way, they’ve helped with efforts to identify and educate potential buyers and sellers of ecosystem services and provide fodder for a CARE-WWF partnership called “Equitable Payments for Watershed Services (EPWS)”.

Katoomba in Uganda

Burgess got the idea for Valuing the Arc after attending a 2005 Katoomba Meeting in Kampala, Uganda (Katoomba VIII) on behalf of Tanzania’s Department of Natural Resources, for whom he was working at the time.

“We knew the forest was storing a lot of carbon, and the whole payments for ecosystem services thing was beginning to emerge,” he says. “The Katoomba Meeting catalyzed a lot of things, and brought a lot of people together.”

Among those people were PES project developers from Mexico, South America, and South Africa.

“I saw what they were doing and thought, ‘Well, that all looks similar to the beginnings of what has happened in Tanzania,'” Burgess recalls. “I figured maybe we could start to go more in the ecosystem service direction here.”

First the Price, then the Payment

“Neil basically realized that he needed to get beyond general statements about the value of nature and show decision-makers where the value lies within their actual landscapes,” says Taylor Ricketts, co-founder of the Natural Capital Project, which is itself a joint project of Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment, The Nature Conservancy, and WWF.

Over the years, Burgess and scores of other researchers had taken a shot at mapping the ecosystems of the Eastern Arc Mountains, and several facts were clear:

First, they knew that area of fog-enshrouded, moss-laden “cloud forests” that capture and store moisture high in the mountains was declining. Second, they knew that farmers were both tapping the mountain streams for agriculture and for their domestic use, including washing in the rivers.

They also knew that downstream rivers were running faster in the wet season and slower in the dry season – and muddier all year long.

But they didn’t know the extent to which each problem could be attributed to specific practices, and they couldn’t determine how much maintaining the upper catchments was worth to end-users such as breweries and water filtration plants.

Building the Team

Once back home in the UK, Burgess mentioned his dilemma to Cambridge Professor Andrew Balmford, who told him about a grant available from the Leverhulme Trust. Balmford applied for and won that grant, while Burgess lined up the University of Dar es Salaam and the Sokoine University of Agriculture, each of which unleashed scores of staff and PhD students to ramp up the mapping process.

“That’s where we come in,” says Ricketts, whose Natural Capital Project (NatCap) supplied a tool called InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs) – a software package that that maps ecosystem services and their economic values.

As NatCap was joining the project, Ricketts applied for and won a grant from the Packard Foundation that complemented the Leverhulme grant – and set to work delivering their piece of the puzzle.

“We’ve basically built a program that plugs into the industry-standard GIS tool,” he explains. “You can map how much carbon is being stored in forests and woodlands, for example, or where people harvest products like medicinal plants directly from ecosystems.”

InVEST also offers modules that map important areas for water supply, flood control, timber harvest, crop pollination, and other ecosystem services. It is freely available on the Internet, and has been downloaded more than 2500 times. NatCap alone is using it to support more than a dozen other projects around the world.

“You can use only the modules you care about, and customize those to your situation,” he says. “Every week, I get an e-mail from someone on the NatCap team telling us about a new project that used the tool, and it’s quite impressive what people are doing there.”

Laying the Groundwork and Priming the Pump

The tedious task of lining up the partners and identifying their responsibilities consumed much of the first phase of Valuing the Arc. After that came identifying the gaps.

“We spent quite a lot of the end of the first year putting together all available data on water flows, timber, carbon etc,” says Burgess. “A lot of the data was from previous work, including the previous project that I’d worked on. We basically compiled all available data that we knew of from the past 20 years.”

The project is broken into six teams: one for carbon, one for water, one for biodiversity, one for timber, one for non-timber forest products, and one for agriculture.

Early Rewards

In 2010, Cambridge University used the carbon team’s map to provide the government with two hypothetical maps showing the state of Eastern Arc carbon decades from now. One map showed the state of carbon sequestration if the government adopted a sustainable development approach to the mountains, and the other showed what would happen under business as usual. (Ricketts and Burgess contributed to a paper on the two scenarios, which was published in the Journal of Environmental Management).

That same year, the Tanzanian government used the carbon maps to demonstrate its growing REDD readiness at the 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 15) in Copenhagen. That led to a grant from the Norwegian government to expand the carbon mapping across all of Tanzania, beginning in January, 2011.

Mapping Other Ecosystem Services

Ricketts says even more tangible fruit will come due when results are published in March.

“For the last nine months we’ve been synthesizing the six services into multi-service assessments,” he says. “Basically, trying to say where the value for each one is coming from, and where the overlap is.”

Some time around March, 2012, they hope to publish the results, showing the impact of different land-use practices on agriculture growth, urban health, urban growth, and other ecosystem-dependent.

“The science is to take the alternative scenarios and tell people what the consequences of each pathway are for a big bundle of ecosystem services,” says Ricketts. “The big bundle is what we’re doing now.”

After the papers are out, they will hold a workshop for stakeholders who have been working with the project for the past five years.

Will Beneficiaries Become Buyers?

As the measurements become more concrete and targeted, Burgess believes the beneficiaries of ecosystem services will become buyers – and for economic reasons, and not just for philanthropy.

“We’ve got a lot of information coming together on habitat quality and on the amount of timber and non-timber resources coming out of the forest, as well as how much forest there is,” he says. “This will all be pretty fundamental stuff for the carbon baseline work in the near term, and should be valuable to the whole payments for ecosystem services arena that’s going to be there in five or 10 years time.”

Jambiya agrees, but says the near-term damage control can best be handled by government.

“The whole intention of Valuing the Arc is to try to establish the true values of these resources and the services that they offer, and through that make arguments for greater investment on the government side for conservation efforts,” he says, adding that private sector investors will still be needed to make the system viable over the long haul.

Additional resources

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.