Understanding Carbon Accounting Under The UN Framework Convention

Before the world can harness carbon finance to save endangered forests, it needs to agree on two things: how to scientifically measure the amount of carbon that goes into and out of trees, soils, and grasses; and how to politically account for those measurements. That’s a central focus of talks this week in Warsaw, and was the subject of a course that the University of California at San Diego and WWF launched earlier this year.

COP 19 Coverage

We covered the COP from beginning to end, with a narrow focus on REDD and those issues still under discussion. Here is the bulk of our coverage, with a few breaking stories omitted.

Demand For Forest Carbon Offsets Rises As Forestland Under Carbon Management Grows sets the stage for Warsaw with a deep dive into the state of forest carbon markets around the world.

REDD, CDM Likely To Find A Place In New Climate Agreement: UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres offers hope that the troubled CDM market and REDD projects will be included in the international climate deal expected to be finalized in 2015.

Understanding Carbon Accounting Under The UN Framework Convention is a work in progress designed to explain in simple terms the complexity of carbon accounting under the emerging “REDD Rulebook”.

Indigenous Leaders Stand Up For Active Role In REDD relates what indigenous leaders expect from forest-carbon finance

REDD Reference Levels Share Stage With Broader Land-Use Issues In Warsaw outlines the issues on the table at the beginning of the talks.

In Warsaw As In California, Forest Carbon Carrot Needs Compliance Stick explores the need for compliance drivers to boost demand for forest carbon offsets.

Forest, Ag Projects Can Combine Adaptation And Mitigation: CIFOR Study highlights the missed opportunities to link multiple benefits in projects that aim to tackle the impacts of climate change.

Dutch Platform Turns Landscapes Talk Into REDD Reality examines a new platform unveiled in Warsaw that could serve as a model for future public-private partnerships for financing REDD+ projects.

The REDD Finance Roundtable: A Quick Chat With EDF, WWF, and UCS takes stock of the talks on the eve of the final REDD agreement.

For REDD Proponents, No Regrets examines the early success of REDD pilot projects despite sluggish progress made in securing policy and financial support at the national and international levels.

US, UK, Norway Launch Next-Stage REDD Finance Mechanism Under World Bank examines a financing mechanism designed to support performance-based payments down the road.

After the talks, we began digging into the decisions and themes of the two-week talk, and will be rolling these stories out as they take shape.

Unpacking Warsaw, Part One: The Institutional Arrangements explores the last-minute deal that lays rules for governing REDD finance through 2015.

Unpacking Warsaw, Part Two: Recognizing The Landscape Reality explores the thinking behind the growing emphasis on “landscape thinking” in climate finance.

Unpacking Warsaw, Part Three: COP Veterans Ask, ‘Where’s The Beef?’ explores the reaction of carbon traders to the Warsaw outcomes and offers a peek into the year ahead.

Further stories in this series will explore the impact of individual decisions within the rulebook, the role that the rulebook can play in helping existing projects nest in jurisdictional programs, and the impact of the rulebook on the private sector.

12 November 2013 | WARSAW | Poland | India has a Constitution; Germany has a Grundgesetz; and the Terrestrial Carbon Accounting world has its Good Practice Guidance for Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) – a 5,000-page compendium of science-based rules for measuring, monitoring, and accounting for the carbon captured in forests, farms, and prairies. Every standard that harnesses carbon finance to save endangered rainforest and Reduce greenhouse gas Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) is built on these Guidelines, and any agreement forged under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) must adhere to them.

If you don’t know the relevant sections of the Good Practice Guidance, you don’t really know carbon accounting – and most of us don’t know them.

That’s bad news for anyone looking to rationally explore these issues, and it’s especially bad news for developing countries looking to harness REDD income to save their rainforests. That’s because developed countries have set aside billions of dollars for REDD, but they won’t start spending it in a big way until they see trustworthy reference levels that tell them both how much carbon is captured in the forests, farms, and prairies of recipient countries and how that carbon content is changing. To earn the trust of investors and environmentalists, those reference levels must have been developed in accordance with the Good Practice Guidance.

To date, however, no developing countries have published reference levels – largely because few people outside a very small cadre of scientists, negotiators, and project developers understand the Guidance. Without that understanding, developing countries can’t establish trustworthy reference levels; and without those reference levels, developed countries won’t start paying for REDD.

In the end, we all lose – because carbon finance is emerging as one of the most powerful tools for reducing greenhouse gasses in the near term and saving endangered rainforest in the long term. In fact, our most recent “State of Forest Carbon Markets” report shows that carbon finance is being used to support the conservation of more than 26.5 million hectares of rainforest. That’s more than all the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo combined, and it’s based only on voluntary markets.

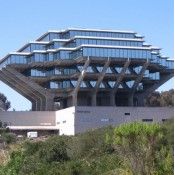

Further growth is limited in part by the lack of understanding, and it was to end this stalemate that the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) launched an intensive month-long course in advanced terrestrial carbon accounting at UCSD’s La Jolla campus. My aim here is to try and re-create the epiphanies I experienced over the course of that month and share them with the larger world. I’ll try to go deep enough into each issue to provide a general reader with enough understanding to follow relevant discussions in Warsaw, but not so deep that I get lost. My aim is to be a conduit between the experts and the larger world, and I invite any real experts who wish to offer feedback to do so. Eventually, I’d like to harvest this to create a simple yet comprehensive and fully indexed overview of carbon accounting – one that can be freely available to anyone looking to understand these issues, and that covers both the voluntary and compliance mechanisms. Think of it as an online “Carbon Accounting for Dummies”.

First Principles

Like most things related to climate science, the Guidelines were developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which gathers research from scientists around the world and distills the essence. Quick history here, segue to:

- Transparency: There is sufficient and clear documentation such that individuals or groups other than the inventory compilers can understand how the inventory was compiled and can assure themselves it meets the good practice requirements for national greenhouse gas emissions inventories.

- Completeness: Estimates are reported for all relevant categories of sources and sinks, and gases.

- Consistency: Estimates for different inventory years, gases and categories are made in such a way that differences in the results between years and categories reflect real differences in emissions.

- Comparability: The national greenhouse gas inventory is reported in a way that allows it to be compared with national greenhouse gas inventories for other countries.

- Accuracy: The national greenhouse gas inventory contains neither over- nor under-estimates so far as can be judged.

Like constitutions, these apparently simple Principles are open to interpretation and subject to debate, as I was to learn as over the course of the next four weeks.

The Basics of Measuring

For a solid introduction to the mechanics of carbon accounting, I suggest dipping into our pre-class assignment: a 2007 paper called “Monitoring and Estimating Tropical Forest Carbon Stocks: Making REDD a Reality”. Written in a year when expectation for remote-sensing were high, it lays out a procedure that combines crawling around on the ground to see what’s there and then mixing it with satellite imagery to see if the pictures from the sky tell us what’s on the ground. It’s a process called ground-truthing, and I’d written about it before. Now I was to learn how it’s done for real.

Week One: The Foundation

The first thing we learned was to differentiate between counting carbon and accounting for carbon. It’s one of those apparently obvious distinctions that still needs to be emphasized if you’re to understand anything that comes next, because it defines everything that reasonable people still disagree over when it comes to REDD in particular and carbon accounting in general.

Carbon counting deals with the science: how you measure the amount of carbon captured in forests, farms, and prairies, as well as the changes in that amount (the carbon flux).

Carbon accounting deals with the politics: how to take those measurements and the factors impacting them and create a global set of rules for translating the changes in carbon stocks and the factors impacting them into ledger entries on which people can make decisions. Like all accounting methods, it will not be perfect. Some scientific issues won’t fit into accounting methods, or some data will be too expensive or even impossible to gather.

Broadly speaking, the IPCC addresses the issue of carbon counting, but only at the behest of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNFCCC, which deals with carbon accounting. In other words, if the politicians who comprise the UNFCCC have a scientific question, they submit it to the IPCC, which culls the world’s scientific papers for an answer.

Lecture 1: The Basics

The first lecture offered a brief history of carbon counting, beginning with a look at late American scientist Charles Keeling’s 1958 attempt to measure the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The “Keeling Curve” begins then and slants rhythmically upward, like an ascending heartbeat.

That heartbeat reflects the rhythm of is the world’s forests, which sponge up carbon dioxide in the summer. It turns out there are more seasonal forests in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere, so the northern summer sponges up more carbon in the spring and winter, while equatorial forests sponge it up all year long and the few southers seasonal forests sponge it up in the southern spring and winter. The upward slant reflects the increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as forests decrease and the burning of fossil fuels increases.

This simple observation offers a springboard into the science of carbon sequestration and the politics of carbon accounting and why we are here – for, although scientists have a pretty good idea of how much carbon goes into oceans and the atmosphere and how much comes from factories, they’re far from sure how much comes from or goes into forests, farms, and prairies.

The Keeling Curve

Lecture 2: Field Measurements and Carbon Inventories

We spent the second day with Conservation Fund Forest Carbon Analyst Jordan Golinkoff, who explained the mechanics of measuring forests before taking us out to the Dawson Los Monos Canyon Reserve to apply our learning.

The take-home is that you want to most aggressively sample the areas that are most likely to have the most carbon. We learned all about how to separate your forest into similar chunks, how to select plots, and how to measure the trees in them. The most common method is to measure the trees in “nested fixed area plots”, which are plots inside plots. In this method, you make a larger plot where you measure only the larger trees, and inside this, a smaller one where you measure the smaller t

Golinkoff, however, says he prefers variable radius plots, which means you use a nifty little prism to measure the probable size of trees in your plot, and then only measure those above a certain radius. It’s the method we’ll be using in the Canyon, and it’s complicated. Golinkoff, however, says it’s more cost-effective and ultimately more accurate because you can survey more plots this way.

Lecture 3: The UNFCCC and Terrestrial Carbon Accounting

Peter Graham co-chairs the UNFCCC REDD+ negotiations, and he led us on a day-long excursion into the history and current state of REDD+ within the UNFCCC. Here is our pre-course reading:

He explained why the opening plenaries of climate talks are so boring (because delegates are just reciting their positions) and how they become more interesting and productive as negotiations break into smaller groups that actually negotiate and then to smaller groups in smaller and smaller rooms, more technological issues come under the gun.

After that, he offered a detailed walk-through of negotiations from 2005, when REDD was introduced, to the present:

Montreal

REDD was formally introduced into the UNFCCC process.

Bali Action Plan 2007

In Bali, negotiators let degradation into the equations for the first time – and left the door open to what later became the “plus” in REDD+: namely, “conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries”.

They established two negotiating tracks – one focused on the existing Kyoto Protocol, and one focused on creating a replacement. REDD talks took place in the replacement track — formally the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA).

Copenhagen

This was the year everything fell apart – except REDD+. For the first time ever, the COP recognized REDD as “crucial” in combatting climate change, and called for the creation of mechanisms “including REDD-plus” to get performance-based finance flowing to developed countries. It called on the UNFCCC to use the most recent IPCC guidance and guidelines as a basis for estimating anthropogenic forest-related greenhouse gas emissions by sources and removals by sinks, forest carbon stocks and forest area changes.

And there was money, too. It even established the Green Climate Fund to xx. On the sidelines, countries like the United States, Norway, and Germany were pledging billions towards REDD – and that figure now stands at xx and counting.

But North Korea sent a ripple of fear through the REDD community when it introduced the concept of Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Activities (NAMAs). The idea was to identify activities that developing countries could undertake to earn credit by reducing emissions, and REDD clearly fit into that category. The trouble is that NAMAs were a whole new mechanism needing a whole new set of agreements. Proponents immediately tried to distance REDD from the new financing mechanism on the block – largely because REDD was so advanced and they feared it would backslide if thrown into this new concept.

Cancun

Sub-national still requires reporting of leakage at national level.

Durban

In Durban, the central question for REDD was how to define a forest – which is no easy task. EXPAND.

If you are applying a different forest definition, you have to explain why. It was recognized by negotatiors that the definition being applied for annex 1 was too restrictive. It was a concern. Durban gives you the leeway to define forests in a way that is most suitable for country circumstances, but must be national one.

For our work, the big deal was that to reduce the burden of explaining great detail every aspect, for practical purposes, a summary would be provided.

if using a different definition for REDD+ than in inventory, will be running two books, and will not serve youwell in long term… Canada had that problem at first, but now can define them the same way… it says you can do it, but

Doha

Here we bogged down – but not because REED. Global talks stalled, and we’re all waiting for Warsaw.

If higher level issues – verification related to NAMAs… financing discussions going on and heated. At a technical level, did make progress, but o reflected in a decision.

Sometimes REDD gets held hostage.

Lectures 4 and 5: IPCC Good Practice Guidance

Thelma Krug is Brazil’s lead climate negotiator and a mathematician with the country’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). More importantly, she was one of the founding mothers – having co-authored the Good Practice Guidance on which we were building all of this.

She walked us through the history of the IPCC, beginning with its first assessment report in 1990 and progressing through the creation of the UNFCCC on Earth Day in Rio two years later and the subsequent Good Practice Guidelines that began flowing in 1996 (after a draft in 1995).

The first focused on Land-Use Change and Forestry (LUCF). It followed what Krug called a “cookbook” approach terrestrial carbon accounting. Accountants loved it, but scientists felt it was too prescriptive. As a result, the 2000 guidance followed a more principles-based approach and introduced a concept that would become a major theme in the coming weeks: how to deal with uncertainty.

By 2003, the term had changed to Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) and suggested that only managed land should be accounted for – raising the question of what, exactly, constitutes “managed land”. In the end, they decided that managed land is any land that either meets certain definitions or the government declares as managed land – on the condition that once it’s declared managed, it can’t be undeclared. Introduce the double-jeopardy aspect.

Finally, in 2006, the term shifted again – this time to Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU). The new name reflected the growing understanding of emissions from agriculture, as well as a reshuffling of categories for farm emissions.

This is also when the principles were introduced.

MUCH MORE TO FOLLOW, FOLKS!!!

Keep checking back to see how this evolves, and if any experts out there have suggestions, feel free to offer them.

Week Two: Applying the Principles

The second week, Anup Joshi came down from the University of Minnesota to explain the intricacies of remote sensing and GIS.

Outline of Remainder

I. Overview of GIS

II. Overview of findings from Costa Rica and the Democratic Republic of Congo

III. Harvesting of lessons from Nepal and Indonesia

V. Guide to statistical analysis

VII. Summary and conclusion

Additional resources

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.