To Save Peru’s Forests, Support Its Small Farmers

Peru is losing more than 80,000 hectares of Amazon forest every year, mostly because small farmers are chopping it to meet our own ravenous appetites for beef, soy, and timber. In the process, they’re generating about half the country’s greenhouse-gas emissions. The country has vowed to change that, and here’s one way they can do so by helping small farmers improve the way they manage their land.

11 September 2017 | The Amazon forest mops up carbon dioxide by the gigaton and acts as a bulwark against climate change, which is why Brazil won accolades for slowing deforestation in the first 15 years of this century.

But 16 percent of the Amazon lies in neighboring Peru, where farmers, miners, and loggers slashed and burned their way through 84,000 hectares of forest per year from 2001 through 2015. That’s more than a million hectares of forest, and it generated half of the country’s greenhouse-gas emissions.

Under the Paris Agreement, the country has vowed to end deforestation within five years, in part by helping farmers big and small become more efficient – but how?

A series of papers from Ecosystem Marketplace publisher Forest Trends, together with Peruvian NGO Mecanismos de Desarrollo Alternos and the Earth Innovation Institute, lay out a plan for tapping international carbon finance, especially programs designed to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+) to promote sustainable land management. The papers advocate the use of “production-protection compacts” (PPC), which finance the sustainable production of coffee, beef, and oil palm, among other commodities, so that “the current vicious cycle can and must be transformed into a virtuous cycle of effective environmental protection and profitable agricultural production on degraded lands.”

The first paper, “Towards a Production-Protection Compact for Peru: Elements and Lessons from Global Experience”, was published last year and takes stock of PPC programs across Africa and Latin America. The second, “The Production-Protection Compact in the Peruvian Context”, was published in March of this year and provides an overview of the Peruvian landscape; while the third, A Financial Strategy for the Production-Protection Compact in the Peruvian Amazon offers specific financing mechanisms that can be tapped to promote PPCs across Peru.

What is a PPC?

A protection-production compact is simply a program that promotes sustainable agriculture by linking finance to conservation. Brazil’s Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural, or “CAR”), for example, provides incentives for landowners to register their properties so that commodities can be traced to areas of deforestation; while sustainable land-development corporations provide funding to large groups of farmers who agree to develop sustainable farming practices.

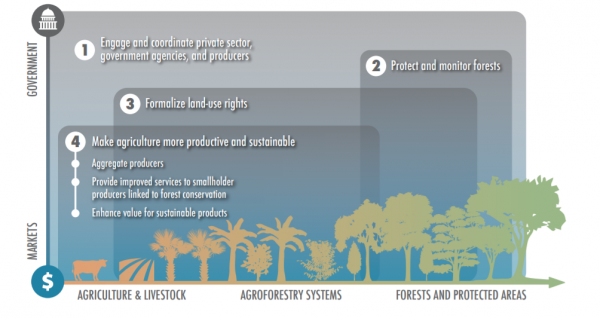

While simple in concept, they’re difficult to implement, because they require coordination among the private sector, government agencies, and producers through a strategically-coordinated multi-stakeholder platform.

Elements of a Protection-Production Compact

The Three Papers

The first paper in the PPC series is the most accessible. It examines six PPC programs across Latin America and Africa and identifies a common development arc that begins with a working group drawing in players from all sectors and then gradually scaling up to a viable program.

It also warns against common pitfalls – the most common being the loss of focus on deforestation.

“If the focus shifts to focusing primarily on increasing productivity for smallholder producers without sufficiently linking these activities to forest protection, activities could have an adverse effect on forests by providing smallholders the technical and financial means to not only improve production in already-degraded areas, but also to seek to implement the improved practices by expanding their farms into standing forests,” the authors write.

The second paper looks at the specific drivers of deforestation in Peru, with a focus on the coffee, cocoa, and oil palm value chains implicated in deforestation. Then it draws on lessons-learned in neighboring Brazil, and offers insight into which aspects can most likely be carried over to Peru, and which might need more adaptation and experimentation. While Brazil succeeded by offering incentives coupled with strict enforcement, they conclude that the smallholder makeup in Peru is more in need of finance and incentives.

“Given the early stage of development of the PPC, its complex nature, the high degree of informality of agricultural production, and the multiple financial, institutional, and human resource limitations present in Peru, a step-wise approach is needed,” the authors write. “In the short and medium terms, increasing market pull and linkages for sustainable products and access to agricultural credit conditioned on forest conservation are the measures most likely to drive the desired changes at the farm level.”

The final paper focuses explicitly on how more accessible credit and technical support can be used to help farmers work together in cooperatives that maintain quality control. It looks especially at REDD+ framework (see earlier), the government of Peru could apply to other sources of climate funding, such as the Green Climate Fund, the Adaptation Fund, and bilateral arrangements with donor countries and development institutions.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.