Shades of REDD+

Nesting: A Good or Bad Piece of Swiss Cheese?

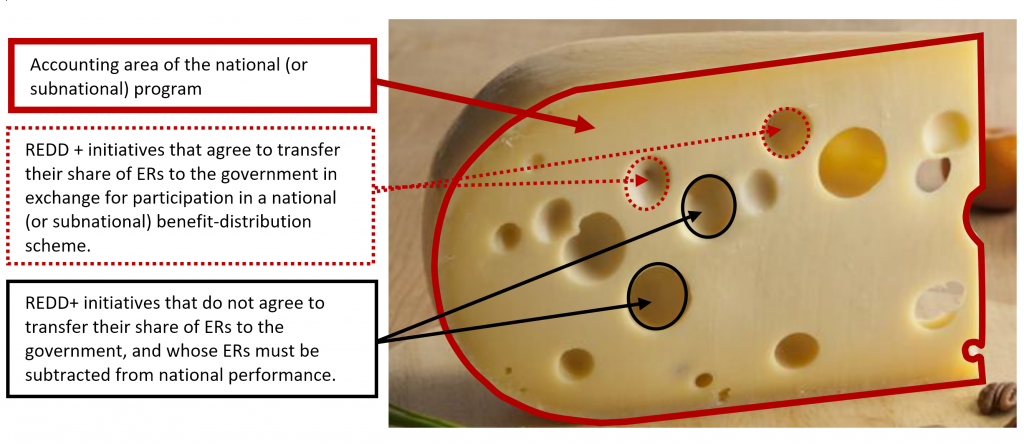

In carbon accounting, many people talk about “nesting” forest carbon projects into jurisdictional programs, but what does it actually look like? Some critics say it looks like “Swiss cheese”, with selected forests cut out of a landscape to develop projects, hindering national or subnational emission reduction programs. This begs the question: Is nesting detrimental to large-scale mitigation… or does it actually enable it?

24 November 2019 | There was a time when people thought that forests were the low-hanging fruit of the climate challenge, and that reducing emissions from deforestation was fast, easy, and cheap. No one thinks that anymore. One particularly significant challenge of tackling emissions from deforestation is the large, diverse, and geographically diffuse set of actors that drive forest loss. Because of this, as we saw in the previous installment of this series (see Bridging the National vs. Project Divide), achieving large-scale mitigation requires collective action from multiple stakeholders undertaking different activities at different levels.

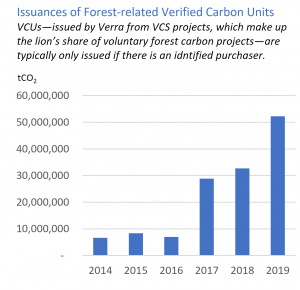

Over the past decade, donor governments have paid for over 330 million tons of CO2 “results” from forest countries. Most of this (over 260 million tons) have been for Brazil’s reductions in emissions from deforestation, with the remaining purchases of around 70 million tons from six other countries. Such results-based payments have been for government-led national (or subnational) programs designed to reduce deforestation, with payments contingent on quantified performance. More recently, purchases of project-based forest carbon credits by the private sector have been rising rapidly (see “Issuances of Forest-related Verified Carbon Units,” below), sourced from a wide range of countries. New pledges by corporate players to offset emissions using ‘nature-based’ credits suggest this market will continue to grow.

Therefore, it would seem encouraging that multiple sources of finance (public and private) at multiple scales (from national to project) are available to provide incentives to a range of actors needed to tackle deforestation.

Therefore, it would seem encouraging that multiple sources of finance (public and private) at multiple scales (from national to project) are available to provide incentives to a range of actors needed to tackle deforestation.

The Challenge: Simultaneous Crediting by Projects and Jurisdictions

Problems, however, have arisen when projects are selling forest carbon credits at the same time governments are trying to access results-based finance from programs such as the Green Climate Fund or the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility’s Carbon Fund. Donors will not “pay twice” for the same emission reduction, so before getting paid for mitigation results, forest country governments are required to subtract credits sold by projects from their estimated jurisdictional performance. In some cases, once a government subtracts project credits, there is nothing left for the government to claim—reducing the “incentive” for government action.

This happens for a variety of reasons. Sometimes it is because the government has not actually taken sufficient action to reduce deforestation. In other cases, it is because national systems to measure GHG performance are substantially different than data and methods used by projects. In order to ensure that these two incentive systems—government-to-government results-based payments and private sector purchase of project-scale carbon credits—work together, countries must develop “nested systems”.

The core objective of a nested system is to allow a variety of stakeholders to take mitigation actions and receive a “fair share” of rewards for their efforts. It involves developing GHG measurement and monitoring systems at project, subnational and national scales that are aligned and setting baselines that promote equity among actors—allowing each to receive finance in proportion to their mitigation contribution.

The Complaint: Nesting Creates Swiss Cheese

Some complain, however, that nested programs create a “swiss cheese” effect whereby project (or subnational) accounting creates a complexity within a country—in effect, creating multiple accounting areas operating simultaneously. The figure below illustrates this scenario on a slice of Emmental cheese. Within a country, some projects may “buy in” to the national (or subnational) program, transferring the Emission Reductions (ERs) they achieve to the government in return for promised benefits. Others, however, may have the right or wish to keep their ERs and find their own buyers (and reap the financial reward). Creating an operational accounting framework for this situation requires a robust carbon accounting framework, transparency and alignment of data, reliable government institutions, clear regulations that provide legal security for those operating projects, and a functioning registry.

Illustration of a Nested System

Those who argue against the swiss cheese often promote one of two ideas: (1) carbon crediting can only occur at the national (or subnational) level; or (2) projects may only issue credits that, in aggregate, fall at or below national performance, as measured by the government. The unintended consequence of the first approach is that REDD+ country governments may be tempted to nationalize carbon rights, ensuring that only one national agency would be recipient of result-based payments. Projects, in such countries, would only be rewarded for their mitigation contribution if—after paying all the costs of the national mitigation program—there is something left to distribute. In the second case, project crediting would be dependent on national performance—providing little predictability for a ‘return on investment’. Both cases reduce the incentive for local actors and dry up private investment.

Benefits of Nesting

Despite their complexity, nested systems may, in some countries, be more likely to mobilize collective actions and achieve large-scale mitigation than a pure national approach, i.e. where only national governments have access to result-based payments. This is particularly true in contexts where governmental institutions do not have the resources to establish and enforce environmental policies and regulations.

Nested systems may also be necessary where the legal right to forest carbon should rest with those who own or have the management right to the forest. Results-based payments to national governments for ERs achieved at the national level may generate conflicts with stakeholders who claim rights to ERs accrued on a variety of lands—including private lands, lands of indigenous people, lands of peasant communities, lands granted in concessions, and lands that are under the jurisdiction of subnational governments. In other words, a national government monetizing all the country’s ERs, regardless of the legal condition of the lands on which they were accrued, may be controversial or even legally untenable in some countries.

Nesting overcomes these problems by allowing carbon finance to go directly to landowners or to those entities to whom landowners have transferred the right to develop and trade ERs on their behalf. It enables a country to leverage the capacities of its entire society to take mitigation actions. It builds on the standpoint that no single stakeholder group should have the exclusive right to access result-based payments and carbon markets, and no stakeholder should be relegated to the role of becoming, at best, a beneficiary of a “benefit distribution scheme” designed by another more privileged group.

While governments are uniquely responsible for accounting of all ERs generated within the national territory, and for achievement of the country’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Climate Agreement, they can enable projects or subnational crediting. Many countries may, in fact, see this as the most promising pathway to achieving large-scale mitigation.

Nesting also sets up a framework that enables private capital to flow into mitigation actions. Where a government has little funding available for forest protection, it may create a policy to drive investment in forest protection activities to ‘hotspot’ areas of deforestation, where innovative approaches to forest conservation can be tested and developed beyond the scope and capability of governmental action. If done right, nesting could allow a country to benefit from the emerging and increasing finance available from companies—a cost savings for the government—without disturbing the government’s ability to also access results-based payments at national (or subnational) scale from programs such as the Green Climate Fund or other donor government funded offers.

For many countries, it is unimaginable that the national government alone, with limited human and financial resources, can successfully address deforestation and forest degradation at the scale required to achieve meaningful emission reductions. The proactive contribution of subnational jurisdictions as well as the material contribution of civil society and the private sector through REDD+ projects are of critical importance for many countries to successfully reduce deforestation and forest degradation.

Emmental cheese is known for its holes but also for its good quality. The price of the slice of cheese is determined by its weight, not by its volume. This, perhaps, is an allegory for a nested system. The presence of “gaps”, or independent projects generating Emission Reductions (that need to be subtracted from the national accounting), need not to imply a loss of environmental integrity or quality of the national program—just as holes in the cheese do not imply poor quality of the product.

Lucio Pedroni is President and CEO of Carbon Decisions International and a leading authority on forest carbon accounting methodologies.

Donna Lee is an independent consultant and serves as an advisor to governments, multilateral organizations, private companies and non-profit organizations; prior to this, she was a State Department official and represented the U.S. in climate change negotiations for several years. She considers herself a proud member of the “REDD+ community” since 2007.

Support Our Work

All environmental challenges are, at their core, pricing challenges: for, if the cost of environmental degradation were embedded in the cost of production, we’d fix this mess overnight.

That’s as true in climate as it is in water and biodiversity, which is why Ecosystem Marketplace has been covering the interplay between economy and ecology since 2005 – long before it was trendy. If you like our work and want to see more of it, then pitch in to help us increase our coverage at this critical time.

You can help out with a one-time donation, or become a sustaining member for as little as $1 per month.

Sign up for E-Mail Alerts

More on the Bionic Planet Podcast

You can also follow our coverage of REDD+ on the Bionic Planet Podcast, which is avaiable on iTunes, TuneIn, Stitcher, and on this device here:

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.