Opinion:

Where Does Healthy Critique End and Cynical Denial Begin?

The science-denial movement delayed action on climate change for decades, and now the same tropes are creeping into coverage of emerging climate solutions. Here’s one way of differentiating between honest inquiry and something more nefarious. Third of a three-part series.

11 February 2022 | A friend of mine, after losing a jiujitsu tournament, praised her opponent.

“Fighting her was like grappling with air,” she said. “There was nothing to get hold of.”

I felt the same grappling with science deniers back in the day – not because they’re nimble (they’re not), but because they don’t play fair.

Liars lie, and we all make mistakes, but science deniers deploy half-truths and innuendo. They don’t necessarily distort their facts but instead embed them in a false narrative, often by building half-truths on half-truths with long strings of rationality between them. In the hands of a skilled denier, half-truths are like signposts that take you just a half-step off course. That might not sound like much, but if ten are lined up with skill and spaced along familiar-looking roads, you’ll find yourself a lot more than five steps from reality.

Whack-a-mole doesn’t work against half-truths and innuendo. Context does, and that’s what I’m trying to provide in this series – first with a look at past media failures, then with a history of Natural Climate Solutions (NCS), and now with a look at the tropes of science denial, drawing heavily on the work of Mark and Chris Hoofnagle.

The two brothers began exposing science denial in the mid-2000s, and scientists from several disciplines kicked their ideas around until broad agreement emerged on the following telltale tropes:

- Setting impossible expectations for what science can achieve,

- Deploying logical fallacies,

- Relying on fake experts (and denigrating real ones),

- Cherry-picking evidence, and

- Believing in conspiracy theories.

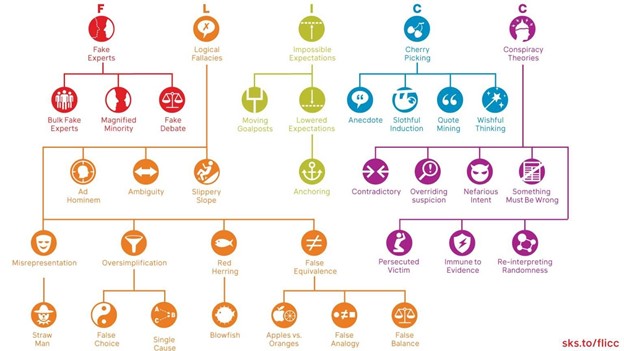

John Cook of the Center for Climate Change Communication coined the acronym FLICC, for “Fake experts, Logical fallacies, Impossible expectations, Cherry-picking,” and he created an extensive taxonomy to provide some structure.

He readily concedes that all these tropes are subsets of the second one, “Deploying logical fallacies,” but he provides a framework that emphasizes those logical fallacies most common to science denial. It’s illustrated here:

Trope 1: Setting Impossible Expectations for Science

Science isn’t about absolutes. It’s about a preponderance of the evidence and concurrence of experts, especially when you have social sciences layered on top of physical sciences, as is the case with forest-carbon methodologies.

Strip away the half-truths and innuendo, and you’ll find that all of the stories I’m discussing in this series do have germs of truth in them, but those germs are pretty innocuous. They all boil down to the fact that forest-carbon methodologies aren’t magical or eternal but instead represent best efforts underpinned by a lively debate over how to improve them. Like the right-wing merchants of doubt who turned the strengths of climate science upon itself throughout the 1990s and 2000s, carbon market opponents are bending over backward to portray lively debate as something dark and sinister while ignoring the complex nature of the challenge we face.

Nearly all of the questionable coverage, for example, takes issue with the use of counterfactual analysis to construct project baselines, often relying on the mere sound of the term to imply that something shady is happening in secret recesses of the climate community.

This is absurd.

Counterfactual analysis simply means you’re looking at a situation and asking what would happen if things were different. It is a cornerstone of the impact analyses, and social scientists have long argued that people use too little counterfactual thinking in environmental policy, not too much. Impact analysis is how government agencies and NGOs around the world determine what works and what doesn’t. It includes process tracing, which means you’re looking beyond correlation to a clear series of causes and effects.

Greenpeace is technically correct when it points out that “it’s difficult to judge if the emissions reductions claimed by REDD+ projects are real,” and I’m sure they’re accurately quoting ecosystem scientist Alexandra Morel as saying, “It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual.”

She’s right, but no one claims otherwise – at least, not since Karl Popper and the triumph of fallibilism. Even physicists don’t “prove” anything. They provide actionable models that work well enough until something better comes along, at which point we change – but only after that better way passes the same tests that the earlier ones did. Living systems are more complex than rocks and crystals, while social systems are more complex than squids and mollusks. That’s why we look at a preponderance of evidence and the majority views of experts rather than outlier events or isolated opinions when harvesting the lessons of the past decade to develop more effective approaches going forward. The goal is continuous improvement in the real world, not imaginary perfection in textbooks.

The late, great statistician George Box used to tell his students that “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” It’s a statement he elaborated on in 1976. “Since all models are wrong, the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong,” he wrote. “It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad.”

Trope 2: Logical Errors

Logical errors are difficult to correct because, unlike simple lies, they can unfold across pages and paragraphs rather than sentences. The facts are often right, but the context is incomplete or the conclusions are, well, illogical.

The Greenpeace story, for example, opens with Britaldo Silveira Soares-Filho, a respected Brazilian cartographer who oversaw the creation of a well-known environmental modeling platform. In 2007, Greenpeace tells us, an unnamed Brazilian NGO invited Soares-Filho and “an array of other academics focused on the Amazon rainforest” on a three-day boat ride down the Rio Negro River to persuade him to “help rubber-stamp a carbon offsetting project.”

2007, you may recall, was a pivotal year for REDD+, and NGOs were trying to get input from as many experts as possible. I’m guessing that boat trip was part of this effort, but we don’t really know because Greenpeace doesn’t tell us the name of the Brazilian NGO, the name of the project he was expected to “rubber stamp”, how he had the power to rubber-stamp it, or who belonged to this “array of other academics” and what happened to them — did they drown? Were they eaten by piranhas?

All we know is that when Soares-Filho got back to his office, he “decided that he didn’t want his world-leading software used for [REDD+].”

I e-mailed him to find out why and he responded immediately.

“Models are used to avert an undesirable future, not predict the future,” he answered. “Models are not crystal balls. Models are a sign to help devise policy and evaluate policy choices.”

That’s not a controversial statement, and most of the people developing REDD+ projects would agree with it – even if they disagree with Soares-Filho’s conclusions on REDD+. He’s not revealing a deep, dark secret here but rather expressing his take on a very public philosophical disagreement that major outlets simply ignored for decades.

To its proponents, REDD+ is a de-facto policy tool. It fills gaps that current policies don’t address and it financially supports policies that exist but haven’t been funded, among other things. REDD+ is, again, a tool for implementing policy or for going beyond policy, but it’s not a magical replacement for policy.

From a REDD+ proponent’s perspective, REDD+ uses modeling the way Soares-Filho advocates: namely, to identify and avert undesirable futures. It does so, however, by using market mechanisms instead of relying purely on command-and-control approaches, and we know Greenpeace’s views on market mechanisms.

There could have been some value in unpacking this decades-old debate and breaking it down for a mainstream audience, but that’s not what Greenpeace did. They framed it as evidence of a deep, dark secret instead of what it is: namely, a philosophical dispute over which reasonable people can disagree, but where a clear concurrence of experts exists.

This is the appeal-to-authority fallacy – namely, framing an expert opinion as evidence rather than what it is – an opinion. Greenpeace does this throughout the piece, where almost every opinion they agree with becomes a “finding” or a “revelation” discovered through an “investigation”, while every program they want to slam becomes a “scheme”. They describe verified results as “promises”, ignoring the fact that funds are allocated for results, not promises.

This verbal sleight-of-hand leads a trusting reader to the next half-truth: an incomplete description of modeling and a dismissal of counterfactual analysis as “fantasy”.

Greenpeace also repeatedly begs the question — another logical error — by citing “findings” that pop up out of nowhere, and they seem to enjoy appeals to ignorance: comparing the probabilistic nature of reference levels to some magical, unattainable certainty.

The fountainhead of all their fallacies is the false dichotomy of offsetting vs reducing internally — the framing of offsets as a “license to pollute.” This is built on the premise that every offset purchased is a reduction not made. I’m sympathetic to this fear, but while plenty of companies certainly do believe they can buy offsets instead of reducing, that’s not what’s happened historically, and the answer isn’t to pretend the offsets themselves don’t work. It’s to enforce high quality on the offsetting front, which will drive up prices, and to embrace protocols for carbon-neutral labeling.

Ecosystem Marketplace conducted an analysis of buyers in 2016 and found companies that voluntarily purchased offsets tended to do so as part of a structured reduction strategy, and plenty of executives have told me that offsetting acted as a gateway strategy. Once they started offsetting, they had a price on carbon, and once they had a price on carbon, they started seeing places to cut emissions. (For details, see “Debunked: Eight Myths About Carbon Offsetting.”)

Bloomberg, meanwhile, has run several pieces on a theme spelled out most clearly in “These Trees Are Not What They Seem,” which takes conservation groups to task for financing their operations through the sale of carbon credits – ignoring the fact that carbon markets emerged in part to overcome the short-term, fickle nature of philanthropic funding. This argument would make sense if money grew on trees, but it doesn’t – at least not without the help of carbon markets. In that piece, the usually reliable Bloomberg commits several logical errors, chief among being a misrepresentation of carbon finance, slothful induction, and oversimplification.

Trope 3: Relying on Fake Experts (and Denigrating Real Ones)

I don’t like the term “fake experts,” because it implies nefarious intent. That may have been the case with the original Merchants of Doubt, but I don’t think that’s always the case here. I instead prefer terms like “false experts” or “false authority. ”

So, what is a false expert? It can be someone whose credentials are dubious, but more often than not it’s someone whose credentials are just not sufficient enough to warrant the status they’re being accorded. That could be a credentialed person whose outlier views are framed as being superior to scientific consensus, which is why Cook’s taxonomy places “magnifying the minority” under the “relying on fake experts” category.

You magnify the minority when you give outlier ideas and untested findings the same or higher status than ideas and findings that have passed the test of time. This is the fallacy the original Merchants of Doubt excelled at, and it’s also a Greenpeace favorite (ironic, since they’re also among the best at outing others who deploy the tactic).

I should emphasize that identifying a person or entity as a false expert doesn’t mean they’re bad people or all their research is flawed, just as even bona fide experts aren’t omniscient. All research should be evaluated on its own merits.

Speaking of research, I’d like to propose a new category called “Relying on Flawed Findings” – that is, findings that aren’t just minority views but are objectively, verifiably flawed – yet still garner inordinate amounts of media attention.

One of these is a paper called “UN REDD+ Project Study,” which comes from a company called McKenzie Intelligence Services (MIS). Greenpeace and the Guardian hired them to evaluate 10 carbon projects in the Amazon, despite the fact that MIS has no discernable expertise in forest carbon. Greenpeace and the Guardian have repeatedly referenced the paper to support their stories, but the paper itself is nowhere to be found.

Why not?

I’ve seen the paper, and the answer is: it’s about what you’d expect from a small company hired to perform analysis outside its area of expertise. Even the title is inaccurate. “UN REDD+” implies they’re looking at REDD+ under the Paris Agreement, when in fact they’re looking at voluntary REDD+ projects – or trying to. The entire analysis is based on how forested areas look from the sky, via low-resolution satellite images, and not on ground samples and models of socioeconomic forces. As if that weren’t bad enough, their photo analysis confused rivers with highways and used forested areas in Bolivia to model deforestation in Guatemala. In the end, it was too embarrassing for even Greenpeace to release publicly, but they and the Guardian continue to cite the fake findings of this phantom analysis in their ongoing coverage.

Another organization to garner undue influence is a small operation called CarbonPlan, which has produced a simple numerical rating system for grading the quality of carbon projects – one of several such efforts underway.

Initiatives like this can be useful as carbon markets finally go mainstream and millions, perhaps billions, of people try to engage them with little prior understanding. Done right, rating systems can provide a useful adjunct to the pass/fail approach carbon standards take as well as additional backstopping to auditors. Done wrong, however, they could institutionalize the practice of magnifying the minority. That, I fear, is the direction CarbonPlan is going.

For one thing, they’re not limiting their ratings to projects that have already gone through broad technical review and public consultation, and they haven’t published any structured methodologies that I know of. Instead, they’re anointing themselves as a sort of de facto standard and putting their stamp of approval on pet projects that are, at best, promising pilots. This could lead to the kind of wildcatting and information asymmetry that George Akerlof warned about in “The Market for Lemons.” That’s a recipe for more confusion and less certainty in a market, which is the opposite of what they claim to be offering.

It wouldn’t be a problem if CarbonPlan hadn’t convinced a handful of reporters and technology companies that they’re the supreme arbiters of quality in carbon projects rather than one voice among many. The fact is they embrace the outlier views of a tiny school of thought spread across a few universities, but those views happen to resonate with a narrow community of well-meaning but deep-pocketed technologists who are acting as a vector to the broader population. In elevating CarbonPlan above the overwhelming majority of experts, these entities are magnifying the minority in a dangerous and destabilizing way.

Specifically, CarbonPlan embraces immediate adherence to pure additionality and pure removals, which I’ll try to summarize simply, based on their published opinions. Pure additionality, as their policy director seems to see it, means carbon finance shouldn’t be used to support activities that do more than just lock up carbon, on the premise that it’s hard to disentangle the carbon benefit from the other benefits. Pure removals means they believe carbon finance should only be used to pay for activities that pull carbon from the atmosphere and inject it into the ground, not those that reduce emissions. CarbonPlan also argues that nature won’t deliver permanence but that untested technologies will, despite reams of evidence on the permanence of natural systems and a dearth of evidence on untested technologies (and the fact that urgency is more important than permanence).

So, why is this a problem? After all, everyone agrees we need to end up at a state of pure removals once we’ve reduced emissions as deeply as possible. That’s the end game. It’s what the whole net-zero movement is all about.

The problem is we’re not there yet.

If we ignore reductions in the present, we’ll face impossible removals in the future, as we saw in the second installment of this series.

It’s great that technologists are pumping money into technological removals, and we should certainly encourage them to keep that work going, but CarbonPlan’s purist approach dismisses existing practices that drive emissions down now. This will take us further away from net-zero if everyone follows it.

Their additionality argument also makes little sense. First, complexity isn’t a reason to avoid something, and second, additionality gets simpler and simpler as prices rise, which they’re doing now. Indeed, there’s plenty of research showing what kinds of interventions become feasible at higher price points, which further demonstrates their additionality.

By ignoring all of these dynamics, however, CarbonPlan gives high ratings to unverified, unvalidated offsets from tech darlings like Charm Industrial while giving low marks to offsets generated under transparent but more complex methodologies that were developed through extensive technical review and public consultation.

That’s not to belittle Charm, or their geosequestration approach, or the technologists who’ve belatedly awakened to the enormity of this challenge. We need to constantly be testing new approaches, and I laud companies like Stripe that are willing to finance new ideas at the pilot phase. It’s wrong, however, to unilaterally anoint this one as ready for prime time, especially if you’re dismissing hundreds of others that really are.

If Charm’s approach really is ready for prime time – meaning if it’s mature enough to warrant the über-high rating CarbonPlan is giving it – they should write up a methodology and submit it to one of the carbon standards. Then it can go through the wringer of peer review and public consultation, where bona fide experts can pick it apart and suggest improvements and broader stakeholders can then provide additional feedback.

I’d love to see them do that and succeed. It would be great for the world, and if they’ve secretly taken steps in that direction, I applaud them. But from what I’ve seen so far, they’ve adopted the “move fast and break things” approach that Silicon Valley loves.

Haven’t we had enough of that?

I understand that the process of developing a credible carbon methodology can be tedious, and it also means putting your ideas out there to be critiqued by experts and opportunists alike. That can be disconcerting, but these review processes evolved for reasons, as we saw in the second installment of this series.

Legitimate carbon standards don’t just provide a stamp of approval based on some media-savvy consultant’s pet theories. They provide a forum through which entities that want to produce a methodology can do so by exposing their ideas to bona fide experts in a formal process of technical review and then passing it out for public consultation and updating as new findings emerge.

Peer-review processes and public consultations are hallmarks of scientific advancement, and CarbonPlan is circumventing them with its unilateral stamps of approval.

Another case of magnifying the minority took place when a paper with the provocative title “Overstated carbon emission reductions from voluntary REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon” went viral over the course of last year.

It came out in 2020 and was one of many using a popular social impact tool to evaluate project baselines. The authors look at deforestation rates in several forested areas and create “synthetic” deforestation rates to serve as proxies for what would have happened if the projects hadn’t come into existence. It’s a process called the “synthetic control method,” which researchers have used to evaluate everything from the impact of decriminalized prostitution on public health to liberalized gun laws on violent crime. The synthetic control method is designed to isolate the effects of an “event or intervention of interest [on an] aggregate unit, such as a state or school district,” according to MIT professor Alberto Abadie, who pioneered its use.

It works not by comparing the impacted city or state to a comparable unit but to a synthetic city or state modeled from multiple states, school districts, or other population centers. Similar approaches have been used to construct baselines under some methodologies, and the paper was an attempt to bring more (not less) counterfactual thinking into environmental impact analysis.

There are lots of challenges in deploying the synthetic control method, not least of which is the selection of covariates. In this case, the authors readily acknowledge a mismatch.

“The construction of our synthetic controls may not have included all relevant structural determinants of deforestation,” they wrote.

Specifically, in constructing their synthetic controls, they excluded the most predictive variables associated with the human impact on individual projects from the criteria they used to identify their synthetic forests. The authors deserve credit for trying a new approach that may still prove insightful, but it’s unclear they have achieved that. Indeed, some of the research they draw on has already been incorporated into new methodologies already under review in the move from stand-alone projects to jurisdictional programs under the Verified Carbon Standard. Specifically, VCS has proposed a shift from modeling based on reference areas to risk mapping based on proximity to indicators of deforestation, such as nearness to the forest’s edge or to recent past deforestation. As you may recall from the second installment of this series, jurisdictional programs are designed to distribute risk between jurisdictions and projects, which is a different dynamic than stand-alone projects were created to address, while all methodologies are designed to update over time as reality changes and science advances.

As we’ll see in a moment, several other studies using similar approaches reached the opposite conclusion from West et al, but all have been roundly ignored by the same outlets and “research” groups, including CarbonPlan, that continue to hype West’s conclusions.

This isn’t a knock on West et al. They generated honest work that’s part of the broader discussion moving the process forward. It’s a knock on those who are magnifying the majority by cherry-picking their conclusions and ignoring all others while assuming that this approach is automatically superior to existing methodologies, which even the authors don’t claim.

That’s unforgivable, but it’s how the hype cycle works. Having built market-based Natural Climate Solutions up into something they could never be, some reporters are now tearing them down instead of digging into them and trying to explain them in all their glorious complexity. To keep the narrative clean and simple, they ignore papers that support the efficacy of carbon markets, and there are plenty.

The most extensive peer-reviewed analysis to date came out after West et al*, but it was roundly ignored by every publication that hyped West’s conclusions, as well as by CarbonPlan, which continues to tout the West et al paper while ignoring anything that contradicts it. In “A global evaluation of the effectiveness of voluntary REDD+ projects,” Coutiño et al looked at all 81 REDD+ projects in tropical forest countries that were over five years old, filtered out those that couldn’t be evaluated for sampling reasons, and settled on 40 that could. Then they concluded that deforestation was 47 percent lower in project areas than in synthetic controls, while degradation rates were 58 percent lower, and the reductions were most pronounced in areas facing the greatest threats. Projects in areas removed from the arc of deforestation weren’t much different from synthetic controls, but the reasons were not addressed, and many of those excluded were in the roughest areas, meaning the overall impact may be greater than they concluded. Findings like that have been emerging across the spectrum, and while not conclusive, they could inform the next generation of REDD+ methodologies as we move to jurisdictional crediting and the nesting of projects in jurisdictional programs.

This is the central narrative of REDD+, but it’s been either ignored or, worse, misrepresented as some sort of “fix” to a “broken” system rather than the latest step in an evolutionary process that was baked into the system at its inception, has yielded tremendous results in the past, and will continue to evolve as reality changes and science advances.

Among the many papers that our crusading anti-REDD+ reporters have missed are a 2017 paper by Seema Jayachandran et al, which looked at the efficacy of payments for avoided deforestation in Uganda, a 2019 paper by Gabriela Simonet et al, which found a 50-percent reduction in deforestation compared to synthetic controls in REDD+ projects along Brazil’s Trans-Amazon Highway, and a 2020 paper by Rohan Best et al that looked at 142 countries over a period of two decades and found CO2 emissions grew at slower rates in countries with carbon pricing than in countries without it. Previous research by Erik Haites et al found reductions were deeper in countries with cap-and-trade markets compared to those with carbon taxes, even though the market prices tended to be lower than the taxes – contradicting a foundational CarbonPlan dogma that high prices are what matter in carbon markets.

Haites et al also showed that cap-and-trade programs become more effective as methodologies are updated, which to me serves again to highlight the importance of constructive criticism and the destructive power of turning the process of discovery upon itself. Patrick Bayer and Michael Aklin found similar results in the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), where emissions were reduced through cap-and-trade even before prices started rising – largely because low prices followed on the heels of reduced emissions, enabling the ratcheting down of caps even further.

All of these studies – and many more – paint a much healthier picture of carbon markets, but you don’t see market proponents running out and spiking the ball every time one of them comes out. Instead, you see standard-setting bodies evaluating these and other findings as newer methodologies emerge, while opponents like Greenpeace and CarbonPlan are constantly spiking their balls, real and imagined.

That’s not a hallmark of honest inquiry. It’s a hallmark of our next trope.

Trope 4: Cherry-Picking Evidence

A related tactic, and another favorite of Greenpeace et al, is cherry-picking, or the practice of selecting only those findings that support your bias.

In efforts as complex as forest-carbon projects, there are plenty of cherries to pick in the form of community members who oppose a given project (and receive inordinate attention despite expressing clear outlier views) or parts of a project that went sideways while the overall effort succeeded. The defense, of course, is to focus on the big picture and a clear preponderance of the evidence, although that can be difficult if the cherries were cleverly picked and packaged.

For a look at systemic cherry-picking, I’ll stick with CarbonPlan and the research they submitted to ProPublica and the MIT Technology Review, which summarized their work in a piece that ran under this headline:

The Climate Solution Actually Adding Millions of Tons of CO2 Into the Atmosphere.

The paper focuses on the California Air Resources Board’s (ARB’s) methodology for Improved Forest Management (IFM), which lets project developers create baselines based on “business as usual” practices, meaning landowners can generate credits by doing more than what’s considered common practice without doing the kind of modeling I described in the second installment of this series.

The methodology arose to prevent aggressive harvesting on thousands of small family forests, hundreds of which change hands every year, and it’s designed to lock those forests up under sustainable harvesting regimes for a century. I won’t weigh in on the actual methodology other than to say it evolved for reasons that critics ignore and which are laid out in the reams of public consultation that were submitted at the time. Much of this is summarized in a court decision that resulted from a failed challenge.*

In its paper, CarbonPlan zeroes in on the way projects estimate the amount of excess carbon that projects keep in trees. Specifically, CARB lets developers use the US Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program, which is based on random samples of forest plots across the landscape. Unfortunately, the FIA didn’t have enough plot points to generate the degree of certainty required for carbon inventories, so CARB created “supersections” of forest that contain enough plot points to reach this.

The problem is that some of the supersections cover areas where one type of tree gives way to another type of tree, meaning that some parts will have higher carbon stocks than others, and some projects will end up getting credit for more carbon than they actually sequester. This shouldn’t happen, and there’s value in calling attention to it, but the authors ignore a remedy CARB applied (and which I don’t know enough to comment on) while implying this anomaly exists across the entire program, which it doesn’t.

This is the cherry-picking part. They zoomed in only on those areas where they knew the anomaly would show up and found that some of the projects probably did get too much credit. They also, however, found that others got too little, and then they declared the entire program a failure.

The paper has lots of other problems as well. The authors back up their claims, for example, by pointing out that an inordinate number of projects end up barely achieving the objectives needed to turn a profit, which to them means the game is rigged. This is silly, because the program is designed to achieve exactly those results.

On top of all this, they mention in passing that they were using the most recently available FIA data to critique old baselines, ignoring the fact that ARB will be updating its program to incorporate that data soon.

One of my great frustrations is that reporters ignore public consultation, which accompanies all of the incremental improvements these standards are constantly making. Some of the comments are technical and wonky, but most are accessible. These public consultations are like ready-made stories: real experts have weighed in on both sides of the issue, and their contact info is always there. Reporters and organizations interested in a better world can engage in and amplify this process, not circumvent it by bringing pet theories to a vulnerable population without providing the context they need to understand it.

That’s not how the process works, and it’s not how methodologies improve. It’s how they get blown up.

Trope 5: Believing in Conspiracy Theories

At the root of all the critiques is a belief that hundreds of biologists, foresters, economists, anthropologists, indigenous leaders, and entrepreneurs have spent 40 years conspiring to create a rigged system that exists to give Big Oil a license to pollute.

It’s the very essence of a conspiracy theory, because there’s no evidence this is the case – and plenty of evidence it isn’t.

None of this means these markets are perfect or that Big Oil is going to transition into clean energy without pressure from above and below. It means there are advantages and disadvantages to every approach, but they all fit together like the pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle.

One advantage of well-run markets is that imperfections are pushed into the open, but that can easily become a liability if we let people exploit it to muddle public discourse instead of raising it to the level it must be if we’re to meet the climate challenge.

We can debate the role of markets all we want, in part by paying attention to the very transparent public consultations that accompany these processes, but we can’t let people who lost the debate run around with baseless claims that “the debate was rigged,” “the markets don’t work,” or “Nordhaus is a fascist.”

Above all, we can’t let a too-compliant media amplify that message. We’ve seen this script before, and it doesn’t end well.

Further Reading

Point-by-point rebuttals exist to all of the coverage I’m discussing here. You can read the rebuttal to the Greenpeace/Guardian story that standard-setting body Verra wrote, as well as the rebuttal I wrote to a ProPublica piece two years ago (and a follow-up I wrote to that one), and the correspondence with ProPublica that the California Air Resources Board (CARB) published after more questionable coverage this year, or one Permian Global Capital wrote after an especially shoddy piece in Nikkei in December. The American Carbon Registry also rebutted a Bloomberg story, but only in PDF format as far as I know.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.