“No Shortcuts to Nature Positive”

There’s high energy out there these days around biodiversity crediting as a tool to achieve “Nature Positive” goals. The World Economic Forum has identified biodiversity credits as a key strategy to unlock finance for nature, and created a dedicated initiative around them. Some carbon market actors tell Ecosystem Marketplace they’re moving into biodiversity as the next big thing. There’s considerable excitement around the prospect of nature-related financial disclosures driving a surge in demand.

McKinsey analysts recently projected a $69 billion market by 2050 under a middle of the road scenario, and $2 billion in demand by 2030. For reference, Ecosystem Marketplace’s last biodiversity market update found that voluntary biodiversity credits transacted perhaps $10 million per annum as of 2017, and that was probably an unusually big year, attributable to the Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme’s efforts at the time – so these are bullish numbers.

The excitement calls to mind the voluntary carbon market in 2019. And proponents of biodiversity crediting are looking at the VCM for useful lessons. They’re mindful of how integrity concerns triggered a massive contraction in the carbon market last year. The World Economic Forum’s biodiversity credits initiative, along with expert groups like the Biodiversity Credit Alliance are working to stand up governance and integrity mechanisms to avoid similar stumbles in the nascent biodiversity credit market.

For ‘nature positive’ to succeed, it must build on lessons learned

In a recent paper published in Nature, experts in the field, all members of the IUCN’s Thematic Group on Impact Mitigation and Ecological Compensation, offers some key principles for achieving nature positive that draw on lessons learned from past experiments in biodiversity crediting, as well as from other nature markets. The authors set out three recommendations to avoid biodiversity markets “amounting to mere greenwash.”

First, don’t abandon the mitigation hierarchy

Biodiversity offset markets have been around for decades, most notably in the United States and Australia. The United Kingdom. Compliance markets for biodiversity mitigation are in fact ten times the size of the global voluntary carbon market, though they receive far less attention. The United Kingdom recently launched its own national “Net Gain” policy, while the head of the European Commission has called to establish a market for biodiversity credits in the European Union.

However, proponents of new biodiversity markets are careful to emphasize that they’re talking about biodiversity credits, rather than biodiversity offsets. Whereas an offset is meant to compensate directly for a negative impact on biodiversity, a credit is presented as a purely positive addition to the sum total of biodiversity, used by its buyer to do good, rather than make up for bad. Given the blowback that carbon markets are facing related to suspicions that buyers are using offsets as a kind of get-out-of-jail-free card, and given the inherent difficulties in ensuring that an offset project will truly compensate for the specific biodiversity values that were lost, this stance makes sense.

And yet distancing biodiversity credit markets from their predecessors also means not learning from that experience.

“Sometimes you hear decision-makers or market actors speak as if ‘nature positive’ is a new solution that will finally fix the challenges of conserving biodiversity,” says Martine Maron, lead author of the Nature paper and a professor at the University of Queensland. “But those challenges have been around for a very long time, and the conservation field has learned a lot about how to grapple with them.”

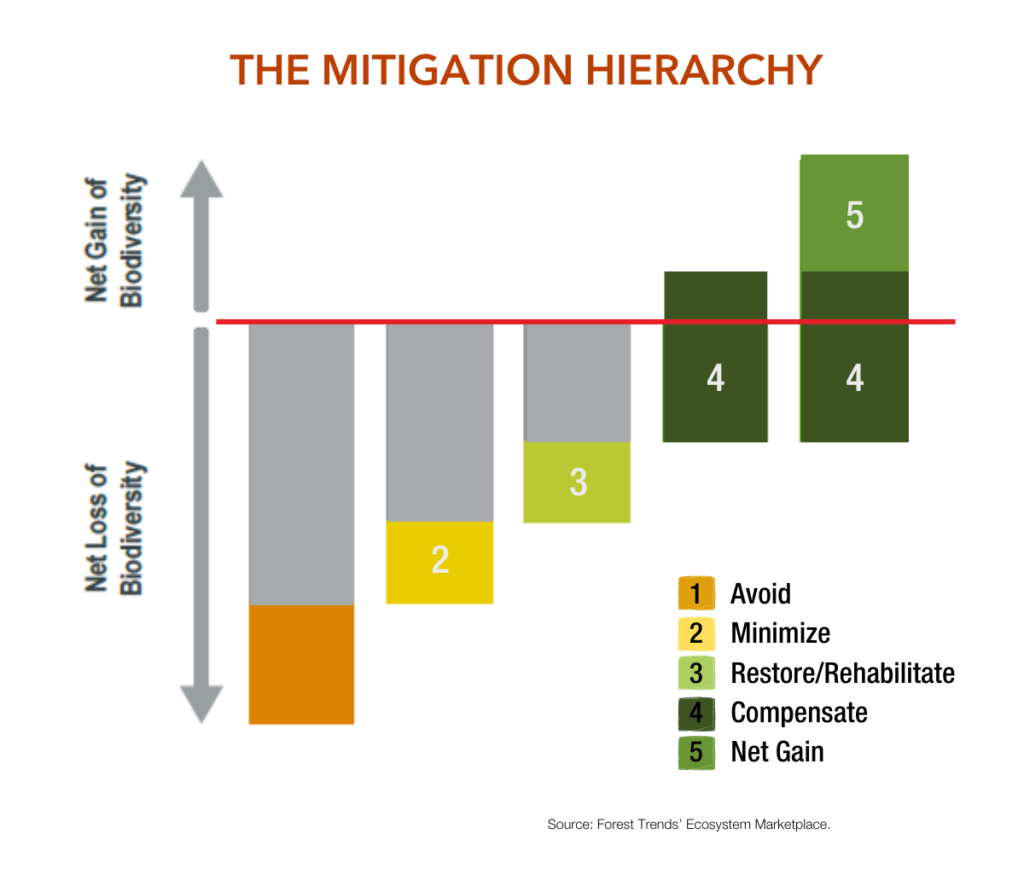

Ensuring that companies and other actors that damage nature can’t simply reach for an offset instead of limiting their damage is a problem that biodiversity markets wrestled with decades ago. Their solution: the mitigation hierarchy. It’s a process consisting of five sequential steps: first, avoid negative impacts on nature to the greatest extent possible. Next, minimize any unavoidable damages, then restore and rehabilitate what remains, and only as a last resort turn to offsets and compensation after all the prior steps have been taken. Finally, biodiversity credits enter the picture in step 5: making further investments to ensure net positive gains for nature.

Rigorous adherence to this process must be a bedrock principle of nature positive, the authors explain. To do otherwise (that is, to purchase biodiversity credits before undertaking the previous steps) is to enter greenwashing territory.

“Companies should not be able to use biodiversity credits to say they are nature positive if they haven’t first fully addressed their negative impacts through the mitigation hierarchy,” says Maron. “There are no shortcuts.”

Engage the full value chain

Historically, biodiversity credits and compensation have been used to address impacts to ecosystems or specific species related to a specific development project, such as a mine, highway, or housing development.

But nature positive requires us to take a broader view, says Amrei von Hase, a co-author of the Nature paper and Programme Director at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

“Nature positive by definition requires us to increase our ambition to include entire value chains and financial portfolios, and to include land, water, and climate – not just biodiversity,” she says.

That is no small task. Companies will need to trace and evaluate their nature impacts along their full value chains or portfolios. Then they’ll need to take steps to avoid, minimize, and rehabilitate impacts. And then finally identify strategies to invest in nature restoration to compensate unavoidable impacts in a “like for like” fashion (i.e., negative impacts on coastal wetlands in Australia should not be compensated by planting trees in Kenya), and additional investments to achieve a nature positive outcome.

“Accounting for and managing a company’s impacts on nature across complicated, globe-spanning value chains is tricky, but not impossible,” says Maron. Tools and frameworks to achieve “nature positive” are emerging to guide the private sector on that path.

Still, ensuring like-for-like compensation can be extremely difficult. That further underscores the need for the mitigation hierarchy, and looking first to avoid and minimize impacts as much as possible. This can be done in part through sustainable sourcing, say the authors.

Biodiversity credits can get companies over the line to nature positive

Achieving nature positive status by 2030 is an immense goal. Consider that while the Paris Agreement gave us 35 years to reach net zero carbon, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Agreement, ratified in 2022, set a timeline of just eight years to do something similar for biodiversity – and biodiversity is inarguably more complex to measure and mitigate than greenhouse gas emissions.

“Nature positive means more nature in the future than at the present,” says Fabien Quétier, a co-author of the paper and Head of Landscapes at Rewilding Europe. “That means that we need to reverse past impacts, not just address impacts going forward.”

This is where well-designed biodiversity credits hold their greatest potential, say the authors. They can provide a vetted, high-integrity, off-the-shelf option for companies and other buyers to contribute to ecological restoration projects and thereby align themselves with a nature-positive future. Ideally, emerging market governance will help drive investments into high-value, hard-to-restore ecosystems, and not only the lowest-cost options when it comes to restoration, says von Hase.

Building the architecture for demand-side integrity

Integration of the mitigation hierarchy is just one piece of the overall integrity infrastructure that needs to be put in place to ensure biodiversity credits can’t be used for greenwashing. The Biodiversity Credit Alliance together with the International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity credits and the World Economic Forum plan to release a set of high-level principles later this year for a high-integrity biodiversity credit market, and are convening stakeholders around producing a potential Claims Code of Conduct, as the Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative (VCMI) has done for carbon markets, as well as other market guidance.

“We can draw on 25 years of experience in biodiversity compensation that have given us best practice like the mitigation hierarchy, as well as looking to other markets for lessons learned and useful models,” says Maron. “We’re not beginning from scratch.”

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.