Momentum For Forest Tenure Rights Rises And Falls Over Last Decade

New research, released today, says a lack of clarity around indigenous and community land rights poses significant risks to investors. And while governments made progress in several low and middle income countries over the last decade to recognize community land ownership, that progress has slowed in the last several years.

This article is an excerpt from the Rights and Resources Initiative’s Annual Review. RRI is a coalition of organizations working in Africa, Asia and Latin America and focused on forest and land tenure policy reform. This excerpt is Part 2, “State of Forest Tenure Rigths in 2015,” of the report. Click here to view this article in its original format and to read the study in its entirety.

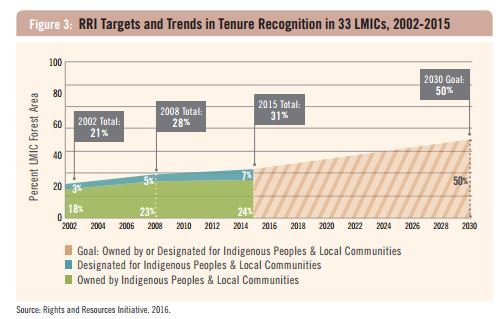

3 February 2016 | NGO and the publisher of Ecosystem Marketplace, Forest Trends, and RRI have been publishing data on forest tenure since 2002, steadily increasing the number of countries covered. In 2005, RRI set a target in conjunction with the Millennium Development Goals to double the forest area owned by or designated for Indigenous Peoples and local communities in 33 low and middle income countries (LMICs) from 21 percent of their total forest area in 2002 to 42 percent by 2015. These 33 countries represent over three-quarters of forest area in LMICs globally. This target was not attained, but governments have made significant progress toward it.

Governments in the 33 LMICs have recognized indigenous and community ownership to a total of 388 million hectares of forest land, and have “designated” an additional 109 million hectares for communities (with a more limited set of rights than under full ownership—see below). Combined, this recognition accounts for almost 500 million hectares of forest land, which is more than 30 percent of the total forest area in the 33 countries, although those numbers are subject to change.

While this progress is important, recognition has slowed since 2008 and its often incomplete nature leaves Indigenous Peoples and local communities highly vulnerable to land-grabbing by governments and corporations in the name of industry and conservation, as well as to the violence that often results when they stand up for their rights.

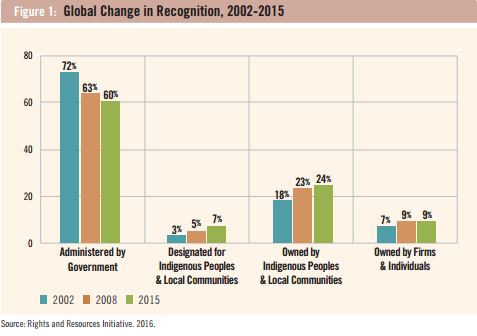

In 2015, Indigenous Peoples and local communities hold formally recognized ownership rights to almost a quarter of total forest land in the 33 LMICs. An additional 7 percent of the total area is designated for use by Indigenous Peoples and local communities; private individuals or firms own approximately 9 percent; and governments still claim ownership to approximately 60 percent (Figure 1).

This increase in the land area to which Indigenous Peoples and local communities have legal rights embodies two trends: governments are hesitating to recognize community ownership, but are more willing to designate lands for Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The area of land designated for communities increased from about 50 million hectares in 2002 to 109 million hectares in 2015. The area of land under full ownership increased from roughly 300 million to 390 million hectares over the same period; in total, almost 150 million hectares were added to the total amount of land recognized as owned or controlled by Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

While more total area was recognized as owned by Indigenous Peoples and local communities between 2002–2015, it represents an increase of less than 30 percent in ownership over 2002 levels. By contrast, the land area that governments designated for Indigenous Peoples and local communities increased by almost 120 percent over the same period, though these numbers are subject to change. While progress in the “designation” of community lands represents progress, it is only a half-measure. It leaves Indigenous Peoples and local communities without core rights, such as the right to due process and the right to compensation in the event that lands are expropriated. Some communities with designated lands may retain property rights for only a certain period. Others lack the authority to manage their lands or to exclude outsiders. Such limitations undermine incentives to invest in conservation and reforestation, and can also make it harder for communities to establish and maintain enterprises based on natural resources. Lands designated for communities therefore tend to be less secure and more easily abused than lands under community ownership.

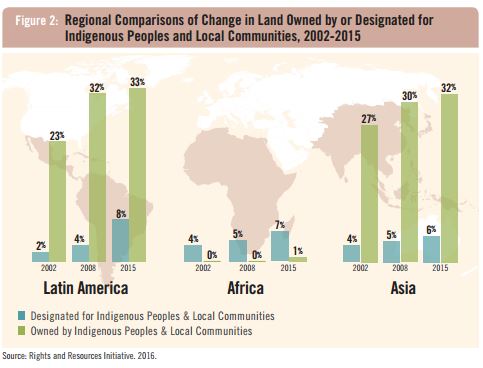

Different regions vary in their commitment to indigenous territories and community-based forest tenure. The highest level of commitment is in Latin America, where governments studied in 2015 recognize indigenous and community rights to approximately 40 percent of their total forest land, an increase of more than 50 percent compared with 2002 (Figure 2).

Of the three main regions, Africa came closest to doubling the area of forest land under indigenous and community ownership and control between 2002 and 2015, with an increase of 73 percent—but this was from a very low base. Currently, indigenous Peoples and local communities own or have limited control of approximately 7 percent of the total forest land in sub-Saharan Africa, but have full ownership rights to only 1 percent. Despite almost doubling the land designated for or owned by communities, Africa lags far behind both Latin America and Asia in total recognition.

The situation in Asia fares better, as Indigenous Peoples and local communities have rights (either ownership or designation) to 38 percent of the total area of forest land. However, current research shows the increase in that area between 2002 and 2015 was the lowest of the three regions, at just 24 percent.

The Future of Forests: New Targets for 2030

A decade after RRI called on the world to double the area of forest land in community hands, we are setting two new targets for 2030 as global indicators of progress within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals:

- At least 50 percent of the total forest area in LMICs is owned or designated for use by Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

- Indigenous Peoples and local communities in LMICs have recognized rights to conserve, manage, use, and trade forest products and services in 100 percent of the land under their ownership or designated for their use.

To achieve the goal of securing formal indigenous and community land rights to at least 50 percent of total forest areas in LMICs by 2030, RRI is challenging governments to accelerate formal recognition, which, as previously mentioned, lagged between 2008 and 2015 when compared to recognition between 2002 and 2008 (Figure 3).

One cannot overstate the importance of these goals for achieving economic, social, and environmental sustainability worldwide, as well as social justice. As explored in the rest of the report, by the close of 2015 many of the arguments, initiatives, and tools to spur progress are now in place.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.