Major Soy Traders Get Low Grades For Cerrado Sourcing

The Brazilian Soy Moratorium is credited with reducing deforestation from soybean production within the Amazon forest by as much as 80 percent in some states, and it worked by getting soybean traders like Bunge, Cargill, ADM, Amaggi, and Louis Dreyfus to stop buying from farmers who clear forested land to grow soybeans.

Unfortunately, the same progress is yet to be seen among companies operating in and/or sourcing from the Cerrado, Brazil’s vast tropical savannah – a region that’s even more biologically diverse than the Amazon is, but that’s seen an 87-percent surge in agriculture activity, with more than a quarter of this expansion coming at the expense of native vegetation.

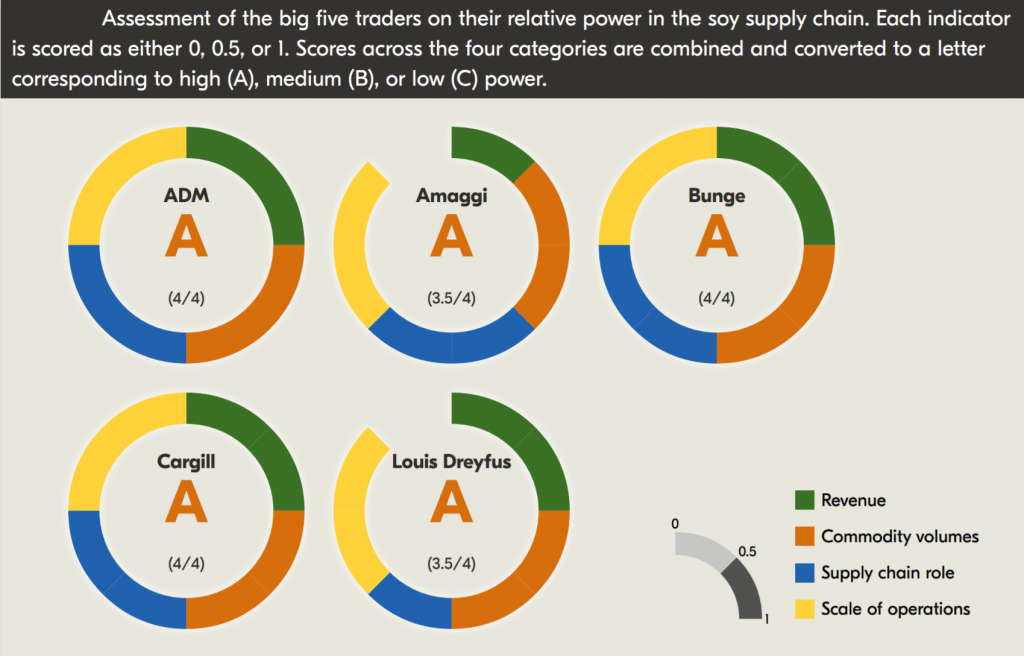

New analysis of the five companies mentioned above – which together accounted for 60 percent of the soy exported from the Cerrado in 2015 – gives all five low grades for approaching deforestation in the Cerrado, and it shows that none are among the dozens of companies that had signed onto the Cerrado Manifesto Statement of Support, which is a pledge that was launched in October 2017 to halt deforestation and native vegetation loss in this ecologically critical region. Indeed, two of the “big five” – Bunge and Cargill – were fined for activities linked to illegal deforestation in the Cerrado.

This analysis is featured in nonprofit research organization Global Canopy’s latest report, “Trading soy from the Cerrado – an assessment of the big five”, which utilized an online tool called “Company action on deforestation” to assess the self-reported pledges and progress, as well as the relative power, of 137 companies sourcing soy and cattle from Latin America.

While all five companies have made deforestation commitments, the report points out, those commitments are narrowly focused on the Amazon and don’t extend far enough to sub-suppliers – although as the report was going to press, Louis Dreyfus, the smallest of “big five”, became the first – and so far, only – to commit to eliminating deforestation throughout their supply chain and conserve ecologically valuable biomes.

“All of the five traders’ commitments fail to fully preclude unsustainable soy production practices because they are all limited in their scope, largely focusing exclusively on the Amazon and on forests, and excluding the Cerrado and native vegetation,” the report concludes, stressing that it does not include the latest commitments from Louis Dreyfus. “Additionally, three of the five traders’ policies are limited to only a subset of their suppliers.”

The analysis comes at a time when agribusiness is ascendant in Brazilian politics, but conservationists argue that food expansion can be increased without destroying native vegetation simply by better managing land that has already been degraded.

Over the past two years, the National Wildlife Federation has been collaborating with The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund and other groups to demonstrate the value to companies to help protect this valuable habitat, and also the opportunity for already-to-use land that doesn’t require additional deforestation and land degradation.

“With millions of hectares of suitable land, that has already been cleared, available for expansion, the soy sector does not need to rely on converting forests and native vegetation,” says Barbara Bramble of the National Wildlife Federation. “The companies that produce, trade, finance and use soy in their products need to recognize this and take immediate steps to ensure that their supply chains protect forests and native vegetation.”

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.