How We Harness an Infrastructure Boom to Close the Biodiversity Finance Gap

This article is adapted from a forthcoming discussion paper, “Habitat Banks: Expanding a Proven Tool to Protect Threatened Ecosystems.”

Global-record levels of investment in infrastructure are, ironically, posing a massive threat to our planet’s infrastructure.

By that we mean natural infrastructure: the natural areas and processes that filter our water, minimize flooding, absorb air pollution, prevent erosion and landslides, and so forth. Living ecosystems like forests, wetlands, or coastal mangroves make our planet livable. And when built infrastructure is planned in harmony with nature, it often works better. Drinking water reservoirs don’t quickly fill in with sediment. Living shorelines complement seawalls. Rain gardens reduce urban flooding.

And yet while spending on infrastructure globally is approaching $9 trillion per year, investment in natural infrastructure lags as a rounding error in comparison. Biodiversity spending garners between $165 and $208 billion a year at most.

In Latin America, deforestation and land-use rates are at unprecedented levels, with the region losing around 2.6 million hectares of forest annually between 2010 and 2020 (FAO, 2020). That’s driven by economic development: the IDB Invest and IFC portfolios in Latin America for infrastructure, energy, agribusiness, water, and sanitation will exceed $9 billion in the coming years. This trend is unlikely to change, particularly considering recent political developments and peace agreements in countries like Colombia, which have led to expanding agricultural frontiers in areas previously inaccessible during the conflict.1 These changes represent immediate economic benefits to communities, but at the same time they also threaten critical biodiversity hotspots and have also driven up land prices by as much as 30% in key regions.

Compensation requirements mean biodiversity finance is poised to increase significantly.

In order to delink new development projects from biodiversity loss, infrastructure lenders, both public and private, are considering new mechanisms for compensating for the impacts of financed projects.

Many are guided by the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Performance Standard 6 (PS6) which requires measures to minimize habitat fragmentation, such as biological corridors; restoring habitats during operations and/or after operations; and implementing biodiversity offsets.

Due to Performance Standard 6 and the IDB Natural Capital and Biodiversity Mainstreaming Action Plan, it’s likely that many IDB, IFC and other development bank projects will need to offset their environmental impacts or invest in nature-positive strategies.

If these tools can deliver direct finance by compensating for the impact on nature of infrastructure development in the amount of just 5% of annual global spending on infrastructure, it could yield $150-500 billion annually, assuming a $9B portfolio. That would go a long way toward closing the biodiversity finance gap, currently estimated at $942 billion per year.

Habitat banking can be a part of the infrastructure finance landscape – delivering faster, more cost-effective, and more durable ecological restoration.

With the uptick of infrastructure investment, especially those investments aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the timing is opportune to work on a country by country and project basis to develop these habitat banking systems into robust parts of the infrastructure finance landscape.

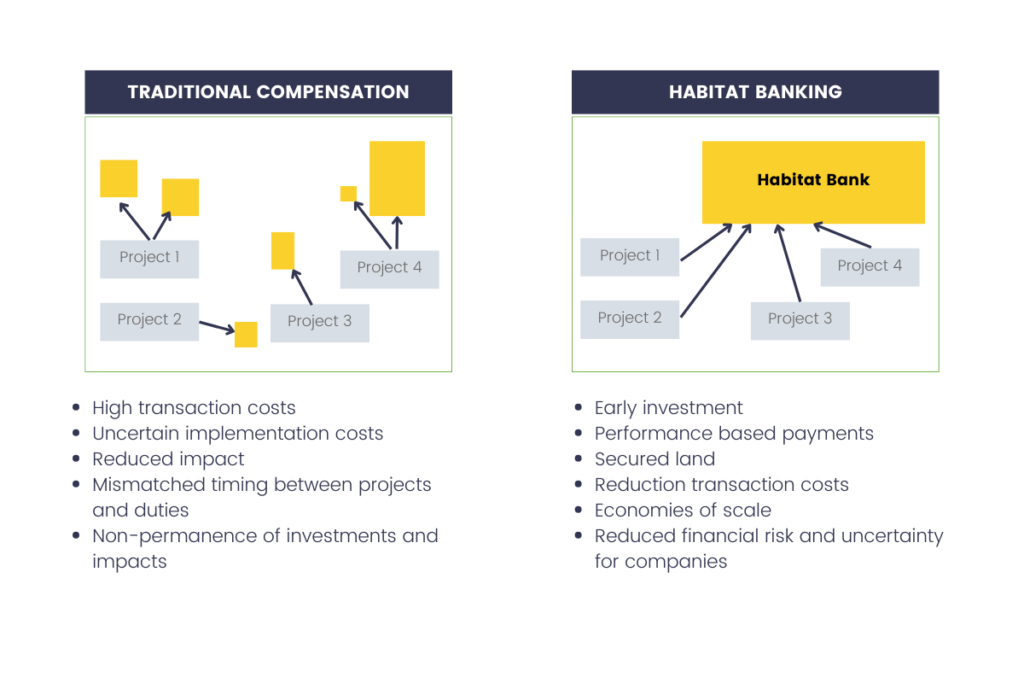

Habitat banks offer a “positively disruptive” alternative to traditional low quality, dispersed, short-term compensation interventions done directly by project developers. Also known as conservation banking, nature compensation systems, or biodiversity offsetting, habitat banking has emerged as a market-based approach to conserve biodiversity by compensating for, or offsetting, the environmental impacts from development, primarily large infrastructure such as roads, pipelines and powerlines, ports and airports, and large agricultural and urban development.

The habitat banking model stands apart from traditional government-run compensation schemes due to its performance-based payments, where funds are either disbursed from an independent trust upon the habitat bank operator achieving statutory milestones or where natural assets cannot be sold until milestones are achieved.

In Colombia, habitat banks that issue compliance biodiversity units offer compelling advantages:

- Cost is lower (10,000 USD/hectare vs 18,000 USD/hectare under traditional schemes). Environmental licensing can cause major delays in infrastructure project implementation, leading to cost overruns. Habitat banks help mitigate these risks.

- Approval times are faster at 12 months versus 26 months, saving costs for project developers.

- Projects boast longer permanence—registered for 30 years versus 12 years by traditional compensation projects.

Note: These numbers are for Terrasos developed projects only, which comprise 10 of the 18 existing habitat banks. Other bank figures are not publicly available.

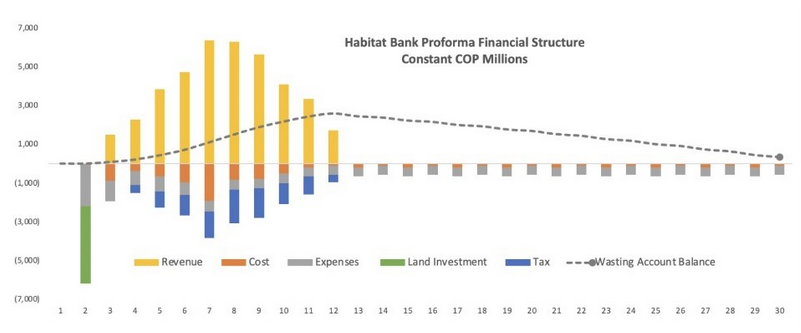

Sample Cash Flows of a 30-year Habitat Bank

Source: Terrasos.

Here’s a quick primer on how habitat banks work.

There are many design features that are critical to make private habitat banks effective. We have summarized here how they operate in Colombia. Others have summarized their features in other countries. The simplest way to describe habitat banks in Colombia is that private companies with biodiversity management experts on staff identify strategic locations to invest in large-scale conservation and restoration projects. The bank generates compensation credits from that work that can be sold to development projects. This model operates on a pay-for-results basis over a 30+ year period, utilizing a sinking fund that is vested over 15 years to ensure long-term ecological stability. All costs including obtaining land use permission, payments for landholders, labor and supplies are bundled into the cost of credits.

Traditional compensation versus habitat banks  Source: Terrasos.

Source: Terrasos.

Habitat banks provide a pathway for voluntary private investments in biodiversity, too.

While mandatory biodiversity compensation driven through infrastructure lending or public policy is one use case, habitat banks could also support greater private investment motivated by financial disclosures on nature and/or demand for nature-positive biodiversity credits.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) encourages and enables businesses and financial institutions to assess, report and act on their nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks and opportunities. This disclosure protocol, though not yet mandatory, is widely in use and increasingly elevates biodiversity as a primary consideration in investment decisions.

Meanwhile, a nascent voluntary market for biodiversity credits or units whereby biodiversity ecological outcomes can be purchased for compensation or contribution purposes has sprung up in numerous jurisdictions. Habitat bank credits may be used to meet this demand, too.

We can realize massive benefits from scaling this tool to more countries.

An investment coalition of philanthropic funders, development banks, private enterprise and NGOs could accelerate the adoption of habitat banking across the developing world. Doing so creates a path for rapidly scaling the funding going to nature conservation, leveraging limited dollars, to create permanent funding where before there was none.

That requires an understanding of the countries industries or financing structures that already have the best enabling conditions for habitat banking across the biodiversity-rich Global South. Dissemination of the lessons from Colombia’s habitat banking program to more countries is critical as is replication of its strongest features alongside those learned in other countries’ experiences. It means engaging with both demand drivers and policy-setters like national governments, multilateral finance institutions, and key commercial banks financing infrastructure development. It also requires building the supply pipeline of high-quality habitat bank projects.

The outcomes could be transformative: massive resource mobilization, restoration happening at landscape scale, more efficient regulation that’s enforced more effectively, and sustained biodiversity gains and climate resilience.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.