How (And Where) Market Mechanisms Can Accelerate Waterway Recovery

17 October 2018 | Twenty years ago, Oregon’s Willamette River was an unswimmable cocktail of 64 deadly chemicals, while the Chesapeake Bay was suffocating under a blanket of algae fed by fertilizer running off of farms spread across six US states. Governments in both regions – and, indeed, across the United States – vowed to fix the mess, in part by embracing something called “Water Quality Trading” (WQT), also called “nutrient trading” – essentially, cap-and-trade for waterbodies.

WQT works by establishing a scientifically-determined “cap” on the amounts of fertilizer or other pollutants that a lake, bay, or stream can handle, and then letting water utilities and other pollution emitters “trade” their allowances to find the most efficient ways of meeting the cap. Many markets also allow these entities to buy credits from farmers and other landowners who, in turn, either reduce their fertilizer use or apply natural infrastructure solutions like planting trees along waterways on their property. Oregon’s Willamette Partnership began to pilot the mechanism in 1996, and a 2000 report from the World Resources Institute said that WQT was “a vast untapped reservoir to resolve the nation’s water quality problems,” that could lead to millions or billions of dollars in savings while accelerating compliance with national water regulations.

But here we are, almost two decades later, and WQT is still limited to a handful of programs, mostly in the continental United States. The Chesapeake Bay program didn’t launch until 2010, and while trading is active in Virginia and Pennsylvania under the Bay Program, it still hasn’t begun in Maryland. Scores of other proposed programs haven’t moved beyond the drawing board.

Why?

To help answer the question, the National Network for Water Quality Trading (NNWQT) has launched a new action agenda with strategies to expand demand for water quality trading. As part of that analysis, Ecosystem Marketplace, with support from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has been helping NNWQT map potential demand for water quality trading.

Mapping and Answer

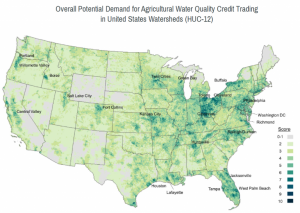

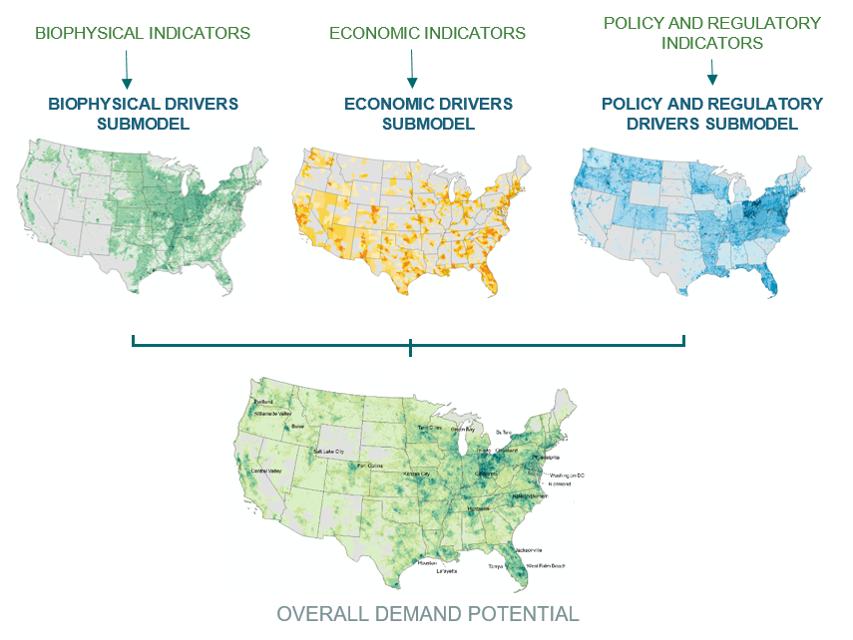

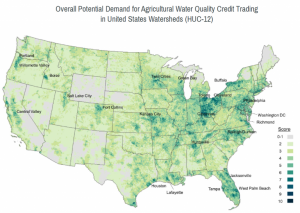

First, we looked at factors we know to be present in programs that are active today. An area must, for example, have a water quality problem that is fixable through trading, so we looked for watersheds with high levels of pollution coming both point sources (like industrial facilities or utilities) and nonpoint sources (like farmland). There must be actors who would purchase potential credits. In many cases, those may be utilities, especially those that are stretched beyond their current treatment capacity and are expecting their water quality challenges to continue grow with increased population and urbanization. We also accounted for policy/regulatory factors, like whether or not an area has water bodies that are listed as “impaired,” where the EPA is authorized to assist states develop plans to improve water quality. If a state already has a trading policy or guidance in place, that can encourage potential buyers to participate. In all, we identified 11 factors, organized into biophysical, economic, and policy/legal sub-models.

Here are the results:

For more details about our methodology and results, check out this StoryMap and slide deck.

What Does it Mean?

There are some results we might expect – for instance, areas where trading is already happening, like those surrounding the Chesapeake Bay and Oregon’s Willamette Valley, scored highly. There are also some surprises. For example, Florida, which currently does not have any water quality trading programs, also scored highly. Many parts of Ohio scored highly too, indicating that although the state participates in the Ohio River Basin Trading Project program, there may be potential to expand.

This model isn’t perfect. Establishing and managing a water quality trading program involves many different elements and stakeholders, and it is impossible to capture and quantify all the complexities. For instance, local and civil society factors play a big role. Water quality trading is more likely to emerge if an individual or institution champions the approach. It helps when regulators have experience managing a trading program, whether for water quality or other environmental benefits like water use or carbon emissions. Those factors are difficult to quantify and map. As such, local “ground-truthing” will be required to evaluate potential demand in greater detail and specificity than a national-scale map can provide.

That being said, models like this have benefits too. Defining our methodology forced us to make our assumptions explicit. It puts all geographic areas on an equal playing field, not just the ones that are familiar to people already involved in water quality trading. It also allows us to take a more data-driven approach to determining where water quality trading may be a viable option for improving water quality.

As the British statistician George Box has remarked, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

What’s Next?

“The map suggests that there is a good deal of potential demand for WQT across the country,” says Forest Trends’ Genevieve Bennett, who co-authored the report. Indeed, over 75,000 square miles of the contiguous US scored at least six. “So a lack of buyers is probably not the main barrier.”

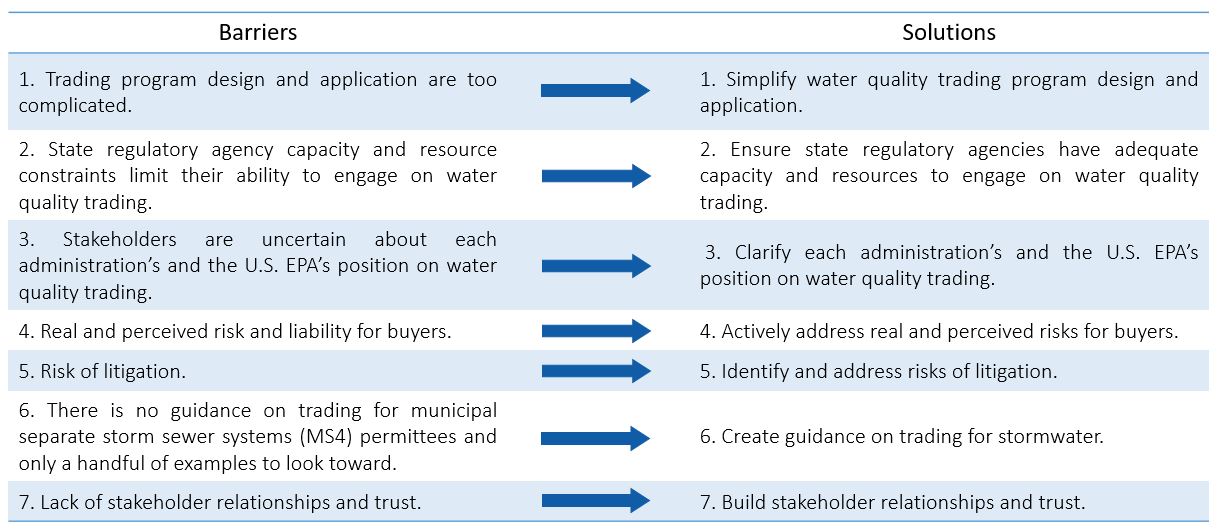

The NNWQT’s action agenda takes a close look at some of the other hurdles that would-be trading programs are facing and suggests how different stakeholders can help overcome them (see below). The next step is to take a closer look at some of the places with high scores, and see if water quality trading would be a good tool to use in combatting water pollution.

Source: adapted from Breaking Down Barriers: Priority Actions for Advancing Water Quality Trading

The bottom line is this: water pollution is a major issue. Nutrient pollution in the US Midwest and Gulf Coast has contributed to the largest dead zone ever measured, spanning over eight thousand square miles from Texas to the Mississippi River Delta in the Gulf of Mexico. It has contributed to the loss of fish and shellfish species in water bodies across the US and around the world, which hurts our ecosystems and our economy. Water quality trading is a cost-effective tool at our disposal, and the better we’re able to use it, and all the tools in our toolbox, the more effectively we’ll be able to maintain healthy ecosystems that support healthy communities and economies.

For more information, check out the StoryMap version of the study (click here to open it in a new browser window):

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.