Guiding The Green Bond Market Toward Big Climate Impacts

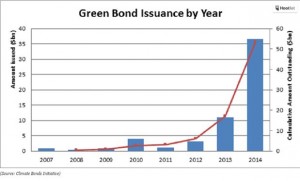

The green bond market experienced a fabulously good year in 2014, with bonds issued three times larger than the previous year. Also in 2014, four financial institutions established the Green Bond Principles to maintain some order, though voluntary, preventing flurries of poorly structured green bonds from flooding this fast growing piece of the climate finance realm.

12 November 2015 | Last year, the French power company, Engie (formally GDF Suez) issued the largest green bond to date at $USD 3.4 billion, allocating proceeds to renewable energy projects. More recently, another French utility, EDF, issued a $USD1.25 billion green bond, following up a 2013 bond that raised $USD1.4 billion for climate-friendly activities such as wind power development. Meanwhile, Dutch consumer goods giant Unilever, issued its first green bond last year as well, a $USD 411 million bond that was oversubscribed three times in the first three hours of its issuance, as investors sought to support the company’s journey toward sustainability. It isn’t just businesses either. Municipalities, including Washington, DC, and other entities are increasingly showing interest as well.

These are clear signals of a significant increase in issuer and investor interest in the green bond market, which is designed to raise funds for specific projects that deliver environmentally sustainable benefits. It’s a space the World Bank pioneered over eight years ago, and one that Scandinavian pension funds and the European Investment Bank originally initiated.

According to the Climate Bonds Initiative, the green bond market exploded in 2014 marking its biggest year ever: $USD 36 billion of bonds issued. That number is three times larger than bonds issued in 2013 and there is great potential for the market to grow much bigger, industry leaders say.

But what are “green bonds”, exactly?

In a broad sense, the term could apply to any bonds issued to finance an environmentally-friendly endeavor – be it a forest carbon project, a wind farm, or a green infrastructure development. Ideally, however, green bonds will earn favorable treatment for the benefits they bestow, and for that to happen, we need more than just a broad sense of what they are. We need a legal definition, or at the very least a set of broadly-agreed principles.

“Anyone can say their project is green,” says Sean Kidney, CEO and co-founder of the Climate Bonds Initiative.

Developing Guidance

In January of last year, a consortium of major banks – specifically JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank – began speaking with investors, issuers, underwriters and environmental groups to create the Green Bond Principles (GBP), which Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have since endorsed as well. And more institutions are endorsing the principles, signing on all the time.

The principles intend to support “voluntary process guidelines intended for broad use that recommend disclosure and transparency and promote integrity in the market.”

What They’re All About

Forging agreement is no easy task – because environmental solutions are something like the mythic, multi-headed Hydra of Lerna.

“One of the big challenges – and opportunities – in the social and green space is that what’s considered ‘green’ is different for everyone,” says Stephen M. Liberatore, CFA, Managing Director and Lead Portfolio Manager of SRI Fixed Income at TIAA-CREF Asset Management, a financial services organization. “I think investors and issuers alike have been looking for a framework that shows them what they’re responsible for.”

There are a lot of issues and questions that come with a green bond and the GBPs, albeit voluntary, offer helpful guidance and understanding, Liberatore, who sits on the GBP Executive Committee, explains.

Indeed, notable green bonds are moving forward in alignment with the GBPs. For instance, to raise funds for its DC Clean Rivers Project, the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority issued a green bond aligned with the GBPs. The huge Spanish corporation Abengoa’s green bond is aligned, as is the Transport for London’s.

And there are several others.

A Four Step Process

The Principles cover four components:

- Use of Proceeds, proceeds must be used on projects that fall under the GBP’s broad criteria

- Process for Project Evaluation and Selection, how does it meet the GBP criteria for being “green”?

- Management of Proceeds, tracking and managing proceeds using an informal internal process and sub-accounts

- Reporting, ensuring transparency through regular reporting of use of proceeds and the allocation of proceeds

Liberatore notes the principles are a living document, continually updated and improved. After the banks released the GBP in January of last year, they released a governance document three months later. In March of this year, the Executive Committee released a 2015 edition with the International Capital Markets Association serving as secretariat.

“I think the principles achieved what we set out to do which is to provide disclosure, transparency and best practices when issuing green bonds,” says Marilyn Ceci, Managing Director, Head of Green Bonds at JP Morgan and a co-author of the GBPs.

The Steady Hand of Guidance

Ceci credits the bank’s early involvement in green bonds as the reason for its participation in establishing the principles.

“We’ve been active in this space since 2010 and once we did the first benchmark green bond, I think we realized the enormity of what could happen going forward,” Ceci says.

Moreover, JP Morgan is heavily involved, essentially, because of popular demand. “The green bond market is a solution to a request from investors and so we as underwriters are responding to our clients and what they want,” says Ceci.

“This is a growing area that the investor base is driving and we’re starting to see the issuer base understand what people are looking for and also what’s required of them,” Liberatore says.

He says data from TIAA-CREF finds that 76% of millennials are interested in socially responsible investing, which green bonds clearly fall under. And according to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, this type of investing grew 929% between 1995 and 2014.

But when there is potential to grow, there’s also a need for guidance which is why JP Morgan moved along with other early actors to establish the GBP. “Without guidance you have people going in different directions,” Ceci says.

And by following the GBP, issuers can find comfort in knowing they addressed key elements of transparency and disclosure, Ceci says.

Alignment vs Compliant

Kidney notes that the GBP are voluntary guidelines and not a regulation. “It’s a cherry pick process. Issuers can pick and choose what parts they will align (not comply) with,” he says.

BNG, for instance, the Dutch Municipal Bank, issued its Sustainable Municipalities Bond in alignment with the GBP with several exceptions-one of them being the bank’s decision to base the use of proceeds on the sustainability of the entity borrowing funds rather than the green project itself.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, voluntary guidelines instead of required standards, Kidney says. At this point, Kidney doesn’t think regulations would be most effective in developing the market. Rather, the focus should be on alignment where different nations follow a similar formula and use the same definitions.

It is important, though, that the market operates under high standards because any type of greenwashing issue negatively impacts it, says Liberatore, who also manages TIAA-CREF’s Social Choice Bond Fund. “If we don’t have a marketplace where these deals and projects perform well over time, we’re not going to get more capital in to fund more projects,” he says.

“NGOs, governments, investors and scientific communities should ensure high quality standards in the green bond market because this will lead to a more robust space. And this market is making a substantial contribution to the rapid transition to a low carbon economy,” Kidney says.

Playing a Role

Because that’s what the green bond market is all about: contributing to efforts to curb climate change and transition to a sustainable economy.

Fixed-income investments, of which green bonds are a part of, can have a large impact on this transition because of its ability to lower the cost of capital for spaces like alternative energy, Liberatore says. “It has a material place in the impact of trying to address climate change,” he says.

Kidney says for the market to be truly impactful, investment must scale up. Importantly though, green bonds demonstrate investor interest which energizes governments and other parts of the private sector to act.

“Solving the climate problem can’t happen entirely on the taxpayer dime and the green bond market is one way of bringing private capital in,” he says.

And the GBP fits in here nicely, Ceci says, as they help ensure the market doesn’t have poorly documented green bonds.

A new edition of the principles is expected out next year.

Kelli Barrett is a freelance writer and editorial assistant at Ecosystem Marketplace. She can be reached at [email protected].

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.