Forests, Farms, And Fields Absorb 15% Of US Carbon Emissions, But Face Uncertain Future. Here’s How To Save Them.

The forests, farms, and fields of the United States sponge up roughly 15% of the country’s industrial greenhouse gas emissions, but that carbon sink is under threat as forests age, urban areas expand, and the climate changes. A new study says carbon finance, green bonds, and a dash of policy coordination can help ensure a robust sink for years to come.

24 February 2016 | We always hear that everything’s bigger in Texas, but what about Alaska? It’s bigger than Texas, California and Montana combined, and its forests hold almost half the living wood of the United States, while its marshes, bogs, and tundra comprise 63% of the country’s wetlands.

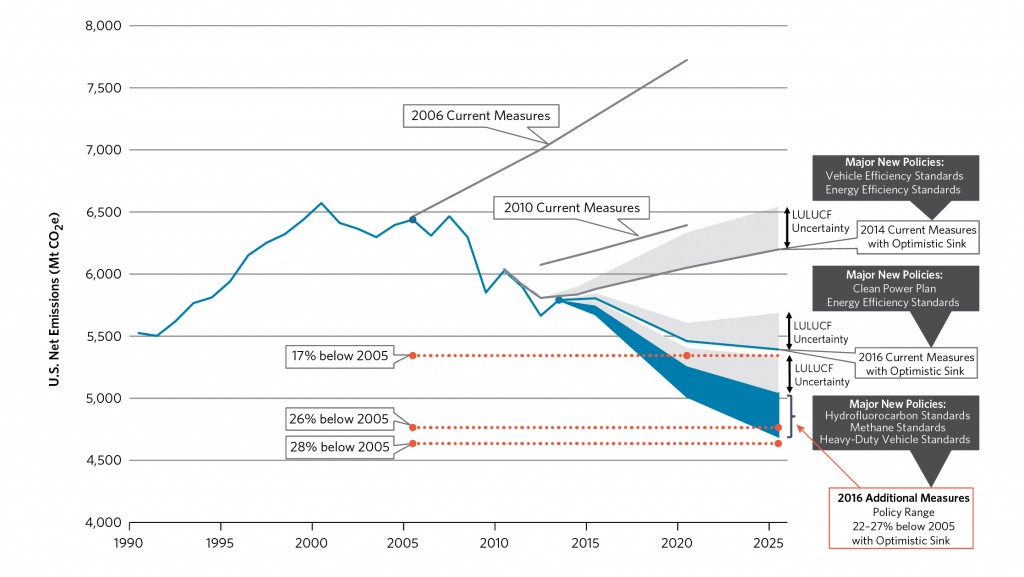

These ecosystems store massive amounts of carbon in their trees, soil, and peat, but no one knows how much is there – let alone how much will go up in CO2 (and methane, for that matter) as the climate changes over the next 20-50 years. That’s a challenge for US climate policy, because the forests, farms, and grasslands of the United States sponge up roughly 15% of the country’s industrial greenhouse gas emissions. If that carbon sink shrinks, then US emissions could creep upwards – and the problem isn’t limited to Alaska.

How Uncertain are We?

“There’s a lot of debate around whether America’s fields and forests will continue to play this large role, or whether the sink will begin to decline,” says Emily McGlynn, a Senior Advisor on Renewables & Environment at Ecosystem Marketplace publisher Forest Trends. “That uncertainty alone is deeply concerning.”

She hopes a new report, “Building Carbon in America’s Farms, Forests, and Grasslands: Foundations for a Policy Roadmap”, will help to reduce that uncertainty.

Co-authored by McGlynn and Christopher Galik of Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, the report offers a detailed but accessible overview of the activities that impact land-based carbon stocks – from cattle-grazing and agriculture to forest management – as well as impacts beyond immediate human control – such as drought and flooding. It then looks to see what is known and what is unknown about the impact of these activities on land carbon, and it takes stock of current policy tools that can be leveraged to promote the management of carbon across the landscape. In the short-term, it calls for more coordination of data, and looks at opportunities to create value for landowners who manage their land to increase stored carbon down the road.

The Alaskan Wildcard

The report is part of an effort called the Land Carbon Policy Roadmap (LCPR) initiative, which Forest Trends launched last year to address the land carbon challenge.

Carbon Payments as Bridge

The authors see carbon markets as a continued opportunity for owners of managed forests interested in preserving their carbon stocks. Opportunities also lie in better integrating carbon considerations into existing incentive programs and developing clear protocols for the creation of climate bonds and other mechanisms to draw private investment into the conversation.

As the report notes, “Any efforts to engage the private sector in land carbon projects should account for the needs of investors and approaches for enhancement of project attractiveness.” In practice, this means creating robust demand for land carbon services while reducing risks associated with project development and implementation. The authors argue that doing so is both an important component of any coordinated effort to maintain the land carbon sink in the U.S. and is potentially doable given the current suite of policy tools available to policymakers.

The Next Steps: Plugging Gaps

The report sets a short-term goal of structuring existing data in a way that’s more accessible to policymakers – beginning by categorizing carbon gains and losses according to their drivers, so that policymakers will be able to better target their actions, and by providing more consistent accounting across the country and more clarity regarding uncertainties.

“We’ve identified a number of policy options for addressing land carbon,” says McGlynn. “The question now is how to start setting priorities. Better data and targeted analysis can help us get there.”

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.