Endangered Species: How Environmental Rollback Could Hit Forest Owners Hard

President Donald Trump plans to revive the rural economy by rolling back environmental regulations, but his policies could cost farmers and forest owners dearly. Here’s a look at some of the farmer-friendly environmental initiatives that could end up on the endangered list – if they aren’t there already.

24 January 2017 | A few years back, the Yurok people of California started tapping carbon markets to save their forest; they’ve since raised millions from companies like Chevron, Tesoro, and Calpine Energy Services by doing so – and they’re not alone. In 2015, owners of farms and private forests across the country earned $63.2 million from those and other companies to keep 6.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from flowing into the atmosphere, according to Ecosystem Marketplace’s most recent State of Forest Finance Report – and that’s just through California’s cap-and-trade program.

It’s a nice chunk of change, but it’s nothing compared to what could lie ahead – if legislators spare federal initiatives that already funnel billions to rural communities across the country and help drive sustainable land use.

Saving The Giant Carbon Sink

Driving these initiatives is a little-known fact: namely the country’s forests, farms and fields absorb about 850 million metric tons of carbon dioxide every year, which means they remove about 16 percent of the greenhouse gasses that the energy and industrial sectors are generating. That makes them valuable, but climate change makes them vulnerable – and that’s where the money comes in.

With the right incentives, land systems can offset up to half the country’s emissions by 2050 – putting tens of billions of dollars into the pockets of farmers and forest owners who maintain the giant carbon sink. Without those incentives, we risk losing our greatest bulwark against climate change – to the detriment of rural communities and the rest of us.

Unlike California and a few other states, the federal government doesn’t have many programs that focus explicitly on land carbon, but it does oversee a national network of environmental markets that can promote water stewardship and biodiversity management, while several departments oversee other programs that support sustainable land management.

Connecting the Dots

I first learned of these scattered programs last year, when Forest Trends (which publishes Ecosystem Marketplace) produced a report called Building Carbon in America’s Farms, Forests, and Grasslands: Foundations for a Policy Roadmap to catch the eye of the Obama administration. It worked, and many of the suggestions found their way into the administration’s Mid-Century Strategy for Deep Carbonization, which looked at greenhouse gases from all industries and included an entire section devoted to forests, farms, and fields.

The administration published its Mid-Century Strategy during the climate talks in Marrakesh – which coincided with the election of Donald Trump, prompting most reporters to ignore it as an obsolete relic of an outgoing administration. It isn’t, because many of the programs it highlights already exist – and they may even grow if more people learn about them.

Both reports make fascinating reading, and here are the highlights.

The Forest Foundation

Forests account for the bulk of that massive carbon sink (see “The Lexicon of Land-Use”, below), which grew by roughly 14% from 1990 through 2013 as the US added roughly a million acres of forest – largely due to government policies.

“This trend has been driven by changing markets and policies, as well as federal programs, which supported tree planting on over 300,000 acres annually over 2006-2011,” the Mid-Century paper points out.

Ironically, the carbon dioxide that’s driving climate change is also contributing to the growth – because trees are essentially gorging themselves on CO2 – but that growth is tenuous, in part because forests are getting older, but also because higher temperatures both tire trees out, increase the risk of spreading wildfire, and perk up nasties like the mountain pine beetle, which is enjoying a “beetle baby boom” and devouring trees across North America.

To save and even expand the giant carbon sink, we have to make it worthwhile for people to expand and manage forests in ways that don’t reduce our ability to make food – and that type of cooperation doesn’t happen by magic. It happens with good land management policy – as we’ll see in a bit.

The Interconnectedness of All Things

Beyond forests, there are farms – which can lock carbon in soil by ramping up “climate safe agriculture” and agroforestry, which involves strategically planting trees on farms in ways that enhance production – by, say, adding fruit to the product mix or “fixing” nitrogen into the soil. This can be expanded to cover more than 50 million acres of farmland while increasing production, according to the strategy paper.

On the demand side, the government can also promote the use of more wood in large structures like shopping centers and hospitals, which is now possible thanks to the development of cross-laminated timber and other technologies. This will slash emissions by making sure the carbon locked in trees stays the wood and also reducing demand for energy-intense products like steel and aluminum.

The Department of Agriculture (USDA) is already providing technical support to the construction sector at doubling the amount of wood used in construction over the next ten years – one of many initiatives it administers under the 2014 Farm Bill.

USDA Choice: One Department’s Tools

The reports look at programs scattered across several agencies, and most media focus on the Environmental Protection Agency, but let’s take a look at a different one: the USDA. Its programs are broadly divided into two camps: easements, which involve paying to permanently set land aside for conservation, and cost-sharing programs, which help landowners implement sustainable initiatives.

“If you want to, say, plant perennial grasses in your pasture, NRCS [Natural Resources Conservation Service – a division of the USDA] will pay 50% of the cost that’s required to do that,” says Emily McGlynn, who is Director for Strategy and Policy at The Earth Partners LP and author of both the Forest Trends report and the land-use section of the Mid-Century Strategy paper.

“EQIP – the Environmental Quality Incentives Program – is the biggest of these cost-share programs, and there are hundreds of different conservation practices that you can do through these programs,” she says, adding that such programs are estimated to keep roughly 50 million metric tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere every year and funnel at least $1 billion per year to farmers and forest owners.

The USDA also provides technical support and funding through a slew of programs identified in the report, and in 2015 it launched 10 Building Blocks for Climate Smart Agriculture & Forestry – a blend of incentive programs, case studies, and other initiatives designed to lock up an additional 120 million metric tons through 2025 and lay the groundwork for future programs.

“The Building Blocks are just meant to be a beginning,” says McGlynn. “In addition to supporting conservation, they spur research that can lay the foundation for more targeted incentives down the road.”

One program, for example, is evaluating different ways of measuring the amount of carbon stored in soils.

“Climate-smart agriculture involves locking carbon in soil, and it’s important that we have certainty around how much a no-till practice can increase soil carbon on a certain soil type in a certain geographic region,” she says. “The more certainty we have, the better we can build protocols around that practice so we can monetize it so that farmers can better access carbon markets.”

Will the Programs Survive?

The Farm Bill comes up for renewal again next year, and McGlynn fears some of the lesser-known programs could wither away just when they should be scaling up.

“Conservation isn’t an entirely partisan issue,” she says. “It seems unlikely that these programs will go away, but if all programs get squeezed in the next Farm Bill authorization, and people are fighting over how to keep their crop insurance subsidy dollars the same, the pressure is to take money away from conservation programs.”

To ensure survival, McGlynn advocates more market-based mechanisms that can bring private funding into the conservation space, rather than continuing to rely on the general tax pool.

More on the Podcast

We’ll also be covering these issues on the Bionic Planet podcast, which you can access via iTunes, TuneIn, or wherever you access podcasts – or click below to listen directly on this device:

The Lexicon of Land-Use

The reports look at all the ways Americans manage land – which scientists call “Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry” (LULUCF) – and found that forests that are mopping up the most carbon.

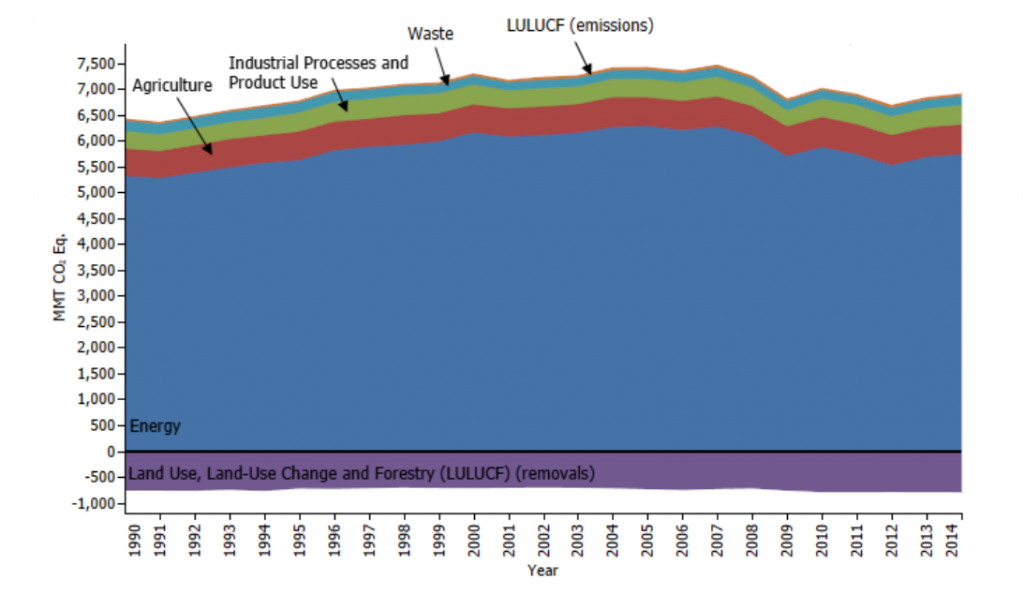

Here are two charts that make that clear. The first is from Page 40 of the government inventory, and it looks at all the different emissions and removals:

Not surprisingly, energy generates the most emissions, which is why it’s the massive blue blob across the middle, with other industries up on top. You’ll see that LULUCF is in the top, too – because some changes generate emissions – but look at the purple band across the bottom: that’s LULUCF as well, and it’s removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

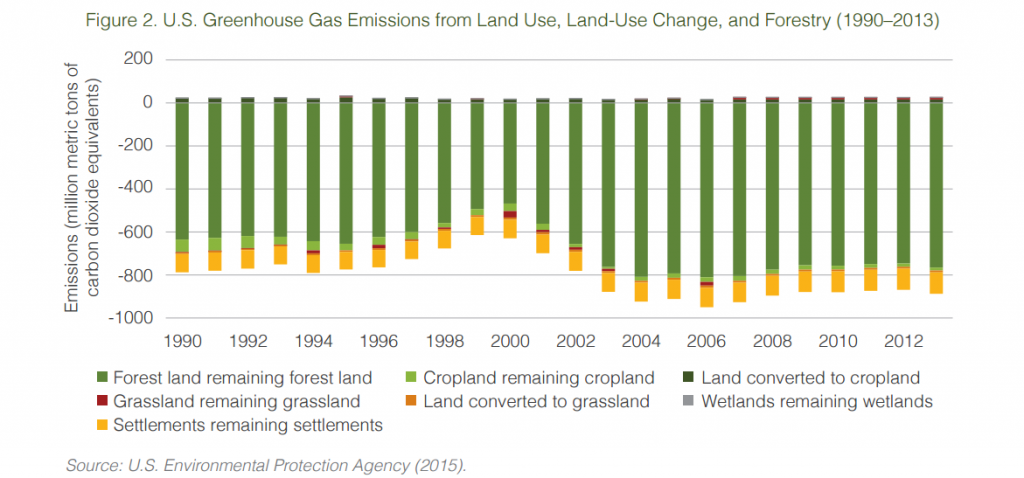

So, which activities emit carbon dioxide and which remove it? For that, we turn to Page 10 of the Farms, Forests, and Grasslands report:

You can dive into the report for details, but the important thing for now are the green bars above – the ones that start to get longer from 2000 onwards. Those show the growth in removals from “forest land remaining forest land”. At the very top of the bars, you see little nubs for other changes in land-use, like “land converted to cropland”. These are the LULUCFs that show up at the top of the first chart, while the others – forests remaining forests, land converted to grassland, etc – are the purple strip along the bottom of the first chart.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.