Bridging The Rural-Urban Divide With Collaborative Landscape Management Tools

Real social and economic dislocation led nearly half of US voters to reject the political establishment and elect Donald Trump as the nation’s next president despite racist and xenophobic rhetroic, says EcoAgriculture Partners’ Sara Scherr. Here, she reflects on what the results mean for those working in sustainable agriculture landscapes domestically and abroad.

Originally posted on the EcoAgriculture Partners blog.

28 November 2016 | The ugly rhetoric of racism, xenophobia and sexism unleashed by the Trump campaign must be roundly condemned and resisted. But it is important to understand that real social and economic dislocation led nearly half of American voters to reject the establishment. Most did so despite disagreeing sharply with that rhetoric (many had voted for Obama in 2012); others found in racism a facile, though erroneous, diagnostic to explain their dislocation and disempowerment.

Rural society under threat

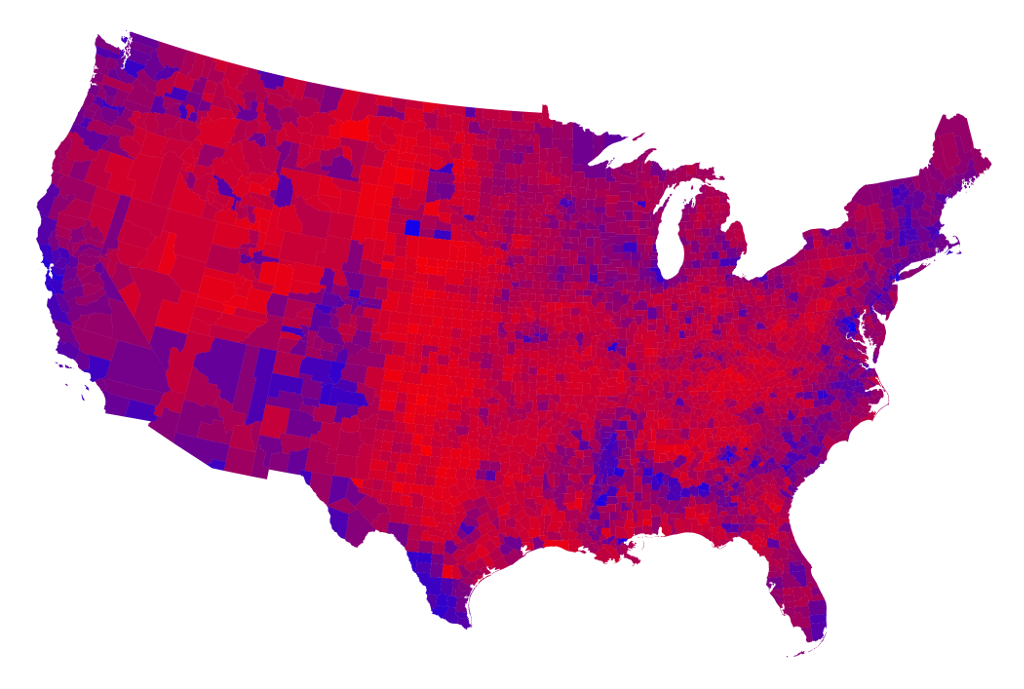

The electoral map paints a striking picture of a rural-urban divide: the patches of bright blue on the TV maps on election night are all around the cities; the patches of deep red are vastly larger, but located where population densities are much lower. The angry calls from economically distressed rural communities in the US (and elsewhere) for an end to globalism—supporting closed borders, tighter trade restrictions, no climate deal, the restoration of economic and social stability—demonstrate a crisis in rural places in the 21st century global political economy. Today’s urban culture devalues traditional agrarian society and increasingly values the non-productive roles of rural places: for nature conservation, recreation, tourism, and a reliable supply of clean water. These tensions and conflicts are embodied in state and national legislation and policy in which rural people have had a limited voice.

While production agriculture and forestry remain core features of American rural economies, policy changes since the 1980s dramatically reduced the number of farms overall and particularly independent family farms, accelerated mechanization, and reduced the number of jobs in agriculture. Consolidation in industrial agriculture and vertical integration in the food industry reduced the power of local communities. More recently, one-size-fits-all regulations addressing the serious environmental costs of industrial farming burdened producers and promoted only marginal changes in practices. There was no associated effort to catalyze agricultural renewal. Public agricultural research crumbled, leaving the field to private companies with a financial interest only in promoting industrial input use. Meanwhile, the heavy manufacturing, mining, refining, and other natural-resource intensive activities that also formed the basis of many rural economies moved overwhelmingly to China, India, and other parts of the developing world.

“There are strong ecological risks to losing or disempowering the local stewards who are in the most intimate relationships with the country’s land and forest resources.”

Indeed, depopulating rural areas has explicitly been held as a vision both by proponents of conventional models of economic growth and by many in the sustainability and environmental communities seeking to provide “more room for nature.” We have just seen the political effects of this casual disregard for the value of rural communities. And there are strong ecological risks to losing or disempowering the local stewards who are in the most intimate relationships with the country’s land and forest resources.

Revaluing rural economy and society

But how can rural communities remain economically and socially vibrant? Answering that question has been a priority for neither the Republican nor Democratic establishment in the U.S., nor development leaders around the world. Part of Donald Trump’s appeal was the perception that he recognized their dislocation and his confident promise to return these jobs and restore social stability. But the solutions presented in his campaign–of repatriating manufacturing jobs, loosening environmental regulations, and overcoming problems through leadership at the top—are questionable at best. Modern manufacturing involves few jobs; where population densities are low, the service sector cannot provide large numbers of higher-paying jobs. The economic costs of ecosystem degradation from industrial farming (not to mention the industrial diet) are felt acutely, if not clearly, in rural communities. Meanwhile, climate change is only further disrupting this picture.

Agricultural production and processing, and associated businesses, can and should remain central to the renaissance of rural America. But these must be reimagined to generate far more quality jobs, and to produce and monetize the ecosystem products and services of agricultural landscapes needed to sustain industry, supply urban populations and ensure agricultural resilience (for example, water, recreation, flood control, biodiversity). In combination these can generate significant economic value for rural areas. So, with hard work, this election can provide an opening in the U.S. for deeper conversations about how to get there. We are inspired by the different kinds of landscape partnerships cropping up all across the United States to meet shared challenges. In the Clark Fork Watershed of Montana, for example, a coalition of groups from agriculture, mining, education and wildlife conservation are advancing together an ambitious community-driven initiative to restore river flow and degraded production lands.

Forging new rural-urban landscape partnerships

The relationship between rural and urban populations needs restructuring and a restoration of mutual respect. Fortunately, a vision of collaboration at a local, landscape scale that focuses on empowering local communities and municipalities to plan their own futures is emerging around the world. By working collaboratively at the landscape scale we can find creative ways, together, to overcome barriers, to manage our shared spaces and resources. This calls for skilled facilitation of extended, mutually respectful dialogue about uncomfortable conflicts, value differences, different understanding of ‘the facts’ and different goals for a ‘good life’. A strong deliberative democracy is not about imposing one vision over another, but about making one’s case as clearly as possible, listening deeply to others, and negotiating mutually acceptable plans of action.

“Communities that are empowered to create and implement a vision for their own future are naturally skeptical of politicians who claim ‘I alone can fix it.’”

I believe this approach is required for resilience against not only biophysical forces like climate change and economic forces like the growth of a knowledge economy, but also from political forces that push citizens who would otherwise reject xenophobia, racism and sexism to tolerate these in politicians who would exploit their despair and anger. Communities that are empowered to create and implement a vision for their own future are naturally skeptical of politicians who claim “I alone can fix it.”

EcoAgriculture Partners as an organization has invested in learning from innovators in sustainable landscape partnerships around the world, and in synthesizing these into tools to support integrated landscape management. We are building models for local access to sustainable finance, exploring creative solutions to shift markets, strengthening the linkages between rural and urban, strengthening local capacities and building the political and economic case for sustainable landscapes. It is not sufficient of focus only on repairing local relationships. Our policy work shows the critical importance of state, national and international policies in enabling effective landscape action, such as valuing the many different services produced by farmers and recognizing locally-devised solutions.

It is clear these solutions are needed as much in Europe and America as they are in Kenya, Guatemala, India, and Indonesia. We know from experience in the developing world that solid landscape partnerships can be forged even in circumstances far more conflictual and financially constrained.

An opportunity

On behalf of the staff, fellows and board members of EcoAgriculture who are based in the U.S., I would like to send a reassuring message to our friends overseas. Our country is remarkably diverse, and even our fellow citizens questioning the globalized economy and fearful of terror have deep ties and valued relationships overseas. We have faith in our strong democratic institutions to put a brake on authoritarian and ultranationalist passions, while also opening much-needed dialogues about the directions of our economy and society. We intend to reach out to those in the new U.S. administration, and to partners in agricultural, environment and development communities, to move forward positively.

Ultimately our landscapes, and the interconnected local partnerships and organizations we create to manage them sustainably and inclusively, can be lifeboats for us in a turbulent world. All those engaged in the challenging work of forging integrated landscape partnerships need to re-commit our efforts and recognize the importance of that work in the larger context of sustainable and peaceful societies.

Sara Scherr is the President and CEO of EcoAgriculture Partners.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.