The Asháninka People Of The Amazon Are Saving The Forest, And Doing It Their Way

A quarter-century ago, the Asháninka people reclaimed a portion of their ancestral territory in the Amazon rainforest and embarked on a journey toward self-rule and sustainable development – sparking in the process the creation of an indigenous ecosystem services protocol that could have repercussions for indigenous people across the Amazon.

First of a two-part series.

23 September 2016| Benki Pianko still remembers the day he and roughly 450 other members of the Asháninka do Amônia migrated down the Amoninha River, from the heart of their territory to its edge, where the Amoninha – or “Little Amônia” – empties into its big brother, the Amônia proper, from which they took their name. Indeed, to most they’re known just as the Rio Amônia People.

On this day in 1992, they began moving en masse in order to establish an outpost from which they could defend their territory, the Terra Indigena Kampa do Rio Amônia in Brazil.

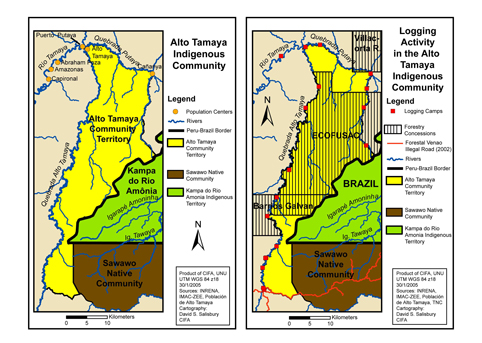

By then, after more than a decade of invasions, illegal loggers had poached much of the “high-value” timber from across the 87,200-hectare territory; but the Asháninka do Amônia had fought them every step of the way, and the forest was mostly intact as a result – except for the patch that the invaders had cleared for farming.

That’s where the Rio Amônia moved, and they named it “Apiwtxa”, which means “Union” in their native language.

Over the next quarter-century, they would develop and then implement a sustainable land-use plan built on agroforestry and the harvesting of non-timber forest products, and they would spread their good stewardship well beyond their territory.

Who are the Asháninka do Amônia?

The Rio Amônia number less than 1,000 but are part of the 60,000-strong Asháninka people, most of whom live on the Peruvian side of the Brazilian border.

Loggers began invading in the 1980s, along with hunters, farmers, and drug traffickers, sparking a decade of fighting that finally came to an end with the help of two outsiders: anthropologist Margarete Mendes and attorney Ana Valeria Araujo of the Nucleo de Direitos Indigenas, who rained a torrent of letters from across Brazil down upon authorities responsible for everything from indigenous issues and environment to land development and law enforcement; and in late 1992, President Itamar Franco officially recognized the land as theirs.

The Return of Agroforestry

When Pianko’s band first moved to Apiwtxa, they experimented with the invaders’ practice of farming rice, corn and beans, but they dropped the practice when they saw what it did to the soil.

“It didn’t really work, and would have accelerated deforestation,” he says “So we decided to focus on handicrafts while developing a land-use strategy.”

NGOs and Brazilian authorities offered training and funding to strengthen this business, and as it grew, the Rio Amônia began to interact more with their neighbors in surrounding areas – prompting them to form the Apiwtxa Association to represent their interests outside the territory.

“This was a major turning point,” says Marcio Halla, an agronomist and consultant for the Communities Initiative of Forest Trends (the NGO that publishes Ecosystem Marketplace). “It not only helped them become more integrated into the community, but also became a focal point around which to increase their governance.”

In 1995, they finalized their land-use strategy, focused largely on agroforestry, which the University of Missouri’s Center for Agroforestry defines as “intensive land-use management combining trees and/or shrubs with crops and/or livestock.”

In 1996, the association heard of an initiative called the Pilot Program to Conserve the Brazilian Rain Forest, which was looking to fund experimental methods of agroforestry. They worked their plan into a formal proposal dubbed Atame Aniro – “the Forest is our Mother” – and were promptly turned down.

Going it Alone

Not to be denied, Pianko and his brothers – all of whom are chiefs – began shopping their proposal to individual donors, and managed to get the program off the ground, while also taking part in regional efforts to train indigenous agroforestry agents. They began reforesting the area that had been cleared, and they undertook an inventory of native fruits and nuts that could be sustainably harvested across their territory.

A quarter century on, the newly-planted trees around Apiwtxa yield an abundance of indigenous fruits like buriti and banana, as well as imported products like coconut and lemon. Apiwtxa even has a tree nursery, where the people grow saplings for export, while they’ve been sustainably harvesting non-timber products like acai and the oil of murmuru, which is an indigenous palm plant.

In 2002, the Acre Association of Indigenous Agroforestry Agents (Associação do Movimento dos Agentes Agroflorestais Indígenas do Acre/AMAAIAC) was formed and worked with the state government to provide a part-time salary for indigenous agroforestry agents.

At the same time, however, illegal logging was picking up over on the Peruvian side of the border.

The Loggers Return

Soon logging on the Peruvian side began spilling over to Brazil, but this time the Rio Amônia were ready for them. As loggers approached Apiwtxa, the Rio Amônia not only stood their ground but called in reinforcements from their Ashaninka brethren on the Peruvian side of the boarder.

Turned away at Apiwtxa, loggers began entering the forest from different routes, and in 2003 the Rio Amônia appealed directly to Environment Minister Marina Silva, a former rubber-tapper who understood the situation well. She eventually called in the Brazilian Army, who removed the loggers from the area.

Since then, the Rio Amônia have dramatically increased their patrols of the area, and skirmishes still take place. As recently as 2014, four members of the Peruvian Ashaninka lost their lives defending the forest before a meeting in Apiwtxa.

Bringing Sustainable Forest Management to the Masses

The agroforestry program became an unqualified success, providing both food and income and spurring the people to take on an ambassador role of sorts, spreading their message of forest conservation and sustainability beyond their territory.

That process began accelerating in 2007, when the Apiwtxa Association purchased 87 hectares of degraded land near the village of Marechal Thaumaturgo and built the Yorenka Atame School to educate neighboring populations on sustainable development practices such as agroforestry.

Around that time, the state of Acre began developing a new legal framework for handling payments for ecosystem services, and they invited indigenous people to help craft the law. Pianko’s brother, Francisco, had participated in the process and asked Ecosystem Marketplace publisher Forest Trends’ Communities Initiative to conduct workshops for his people.

Ecosystem Services for Acre

In 2010, Acre launched the System of Incentives for Environmental Services (Sistema de Incentivo a Serviços Ambientais, or “SISA”) to finance land stewardship. SISA creates a framework within which laws and regulations can be created for payments that flow to people who manage the land so as to capture carbon, preserve biodiversity, and manage watersheds, among other things.

In 2012, the German Development Bank, KfW, pledged 50 million Real ($24.2 million) to the state of Acre through SISA to support indigenous activities that save forests and reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation of forests (REDD+). The first payment came in January, 2014, and included R$3.6 million ($1.6 million) for AMAAIAC to pay its indigenous agroforestry agents.

Scaling it Up; Doing it Right

By late 2014, SISA money made it possible for AMAAIAC to employ more than 140 full-time agroforestry agents across Acre, including three in Apiwtxa alone – who, in turn, are training other members in agroforestry practices.

The Rio Amônia, meanwhile, were also ramping up their efforts to support sustainable land-use outside their territory. They began working with rubber-tappers in Alto Jurua, a nearby extractivist reserve, and won R$6.6 million ($2 million) from Fundo Amazonia to scale up their training programs and beef up their forest patrols with physical outposts rangers.

“The Alto Jurua project is incredibly important, because extractivists and indigenous people didn’t always get along in the past,” says Halla. “Now, they are working together, and the Rio Amonia are developing a strategy for the conservation in the whole region, and in a way that’s very innovative, very strategic.”

By the end of 2015, that strategy had also won R$220,000 ($68,000) from SISA, although it could arguably earn much more.

Land-Use Protocols and Ecosystem Services

SISA was designed with explicit environmental outputs in mind, so that donors like KfW could pay for specific results, such as preventing the release of carbon dioxide through REDD+ payments to the state government, which in turn funnels the money to activities it believes will do that.

Individual peoples and territories could also receive payments for environmental outcomes, but the Rio Amônia aren’t sure they want to go that route.

“They fully recognize the concept of ecosystem services, and they have a proven record of success, but they were leery of getting into a situation where they were getting paid for specific actions and outputs imposed on them from the outside,” says Beto Borges, Director of the Forest Trends Communities Program. “Their argument was: ‘Our community and our way of life support the forest, and we can prove it, so if someone wants to support us, it should be to support the activities that we know work, rather than what some outsider believes will work.’”

In 2015, Halla joined the Forest Trends team and participated in his first workshop.

“It took me a while to understand what they were getting at,” he says, “But it came down to this: They felt they needed to communicate their philosophy to the outside world and get support for continuing it holistically, without complicated metrics.”

Halla had been working with an extractivist reserve that wanted to clearly define the terms by which they sold their products, and he had that definition in his computer.

“I open it up and showed them a forest-products protocol I had some involvement in,” he says. “It was for an extractivist reserve that was trying to set the conditions to sell their forest products to companies – the terms, the conditions of the contracts for trading, etc – and then I suggested it could be an interesting tool for them because the biodiversity law was just approved, where the community protocols were first mentioned as a legal tool.”

Pianko, Francisco, and others gathered around as he explained the protocol.

“I have two others examples I can bring next time,” he said.

“Please do!” they answered.

In the second installment, we explore in detail the evolution of the Ashaninka Environmental Services Protocol, what it entails and the Rio Amônia’s reasoning for creating it.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.