Opinion

A Tale of Two Transactions: the Corresponding Adjustments Story

The Paris Agreement provides a global framework for tracking and transferring greenhouse gas reductions at the national level. Carbon markets provide a way of enabling those reductions through cooperation. One requires a corresponding adjustment, while the other one doesn’t, as Jos Cozijnsen explains.

This article is adapted from a story that first appeared on the Emissierechten blog. It is part of an ongoing effort to share opinions from thought leaders on a diverse range of issues. The views are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of Forest Trends or Ecosystem Marketplace.

18 December 2020 | The nation of Switzerland and the oil company Total, of France, are two completely different entities. One is a nation with thousands of companies and millions of people in it, while the other is a private company with operations in scores of countries. Both, however, have one thing in common: each has committed to slashing its net greenhouse gas emissions.

Switzerland aims to cut the combined emissions of all its factories, cars, and cows in half by 2030 and to slash them to zero by 2050 – right in line with what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says all countries must do if we’re to meet the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting global warming to an average of 1.5°C (3.7°F) above preindustrial levels. The country, however, says it can only reduce by 37.5 percent in the next ten years using existing technologies, so it will get to zero by imposing a cap on emissions and purchasing international carbon offsets that finance reductions in other countries for another 12.5 percent. For now, the country is executing these transactions itself, but it may make it possible for large emitters to do so themselves.

Total aims to offer net-zero LNG to customers who want it as soon as it can, no matter where they live. Total argues LNG has lower emissions than oil, but the technology isn’t yet advanced enough to offer emission-free LNG around the world. So it, too, is using carbon offsets.

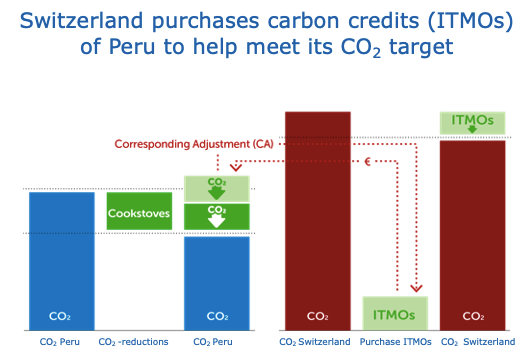

Switzerland is an example of the “governmental CO2 market”: the government is purchasing emission reductions, technically termed “Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes ” (ITMOs), to help meet its national obligation under the Paris Agreement. ITMOs are tradable reductions beyond reductions that the country selling them needs for its own Paris commitments (“NDCs,” for “Nationally-Determined Contributions”). Accordingly, the ITMOs will be transferred out of the selling country, where the reductions actually take place, and into Switzerland’s national greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory. This is termed a “corresponding adjustment” under the Paris Agreement.

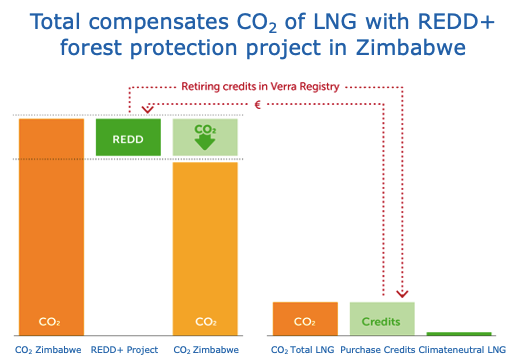

Total is an example of the “voluntary carbon offset market”: the company is buying offsets to create a product that it can market as “climate neutral” rather than to meet a legal requirement. It is buying the offsets from a private company in one country to create a climate-neutral product that will be sold in another country, but the emission reductions will be credited to the GHG inventory of the country where the reductions take place. Total is, in a sense helping another country reduce its GHG emissions, but its only real claim is to having a climate-neutral product. As a result, there is no need for a corresponding adjustment – or shouldn’t be.

Here’s a deep dive into both of the above scenarios.

Switzerland and Peru Agree on Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs)

In mid-October, Switzerland and Peru agreed to work together to increase both countries’ climate ambition. Switzerland, as we saw above believes it can reduce emissions 37.5 percent in the next 10 years, but can achieve a net reduction of 50 percent by using the global CO2 market to finance reductions abroad. According to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, a country may use the surplus CO2 reduction of another country to help achieve its goal through so-called “Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes” (ITMOs). Countries indicate in their climate plan which reductions they definitely want to achieve: “unconditional”; and which can only achieve with international support: “conditional”. Peru’s “unconditional” CO2 target is a 20 percent reduction from “business as usual” (approximately 14 percent above 1990 level). Peru indicates that it can reduce 10 percent more under the “condition” of “carbon financing”.

The countries have different economies and different resources. Specifically, Peru has leeway to reduce more with regard to forest protection and renewable energy, while Switzerland has little in the way of unoccupied land that can serve this purpose. So Switzerland has invested €20 million in the Tuku Wasi program, among other things. The program reduces emissions in Peru by distributing efficient cooking appliances, which means that less wood is used and less deforestation takes place. Peru is also negotiating similar CO2 agreements for the waste sector with Scandinavian countries. One part of the extra reductions counts towards the Peruvian CO2 target; the other part for the Swiss (see figure below).

They agree that the reductions transferred to Switzerland (ITMOs) will not be counted twice. That is entirely in accordance with article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. This means that Peru will deduct the reductions that it transfers to Switzerland from its own reporting via a corresponding adjustment. In doing so, they anticipated implementation rules that will be agreed at the Climate Summit in Glasgow at the end of 2021 or the next Summit. New Zealand Environment Minister James Shaw told Carbon Pulse in November that Art 6 rules can even emerge earlier from these kinds of deals rather than from the UN talks themselves. Peru just launched an emissions reduction registry at IHS Markit to help track activities and the future transfer of ITMOs.

Climate-Neutral LNG

Total announced that it will supply their “First Carbon Neutral LNG Cargo” to China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) in Dapeng. The LNG comes from a production location in Australia. CNOOC thus sells CO2-neutral gas to domestic customers. The user remains responsible for the CO2 emissions from the use of the gas. Earlier this year, CNOOC already bought climate-neutral LNG from Shell.

The CO2 emissions from production and transport are offset by two CO2 reduction projects:

- The Hebei Guyuan Wind Power Project to replace coal power in North China, certified through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and

- Kariba REDD+ Forest Protection Project, which protects forest from logging in Zimbabwe, certified by the VCS (Verified Carbon Standard).

The reductions for wind energy and forest protection help meet the CO2 targets in China and Zimbabwe respectively. Total does not reduce the CO2 emissions with this of its own installations in Australia. These investments are on top of that. Large CDM wind projects like the above are no longer used by most compensation providers because these are already commercial and profitable. Moreover, the Kyoto Protocol, in which the CDM is regulated, will end this year and the CDM will therefore also expire this year. REDD projects and cookstoves projects, such as in Peru, are widely used in the voluntary CO2 market.

The CO2 market will play a role in achieving the Paris Agreement

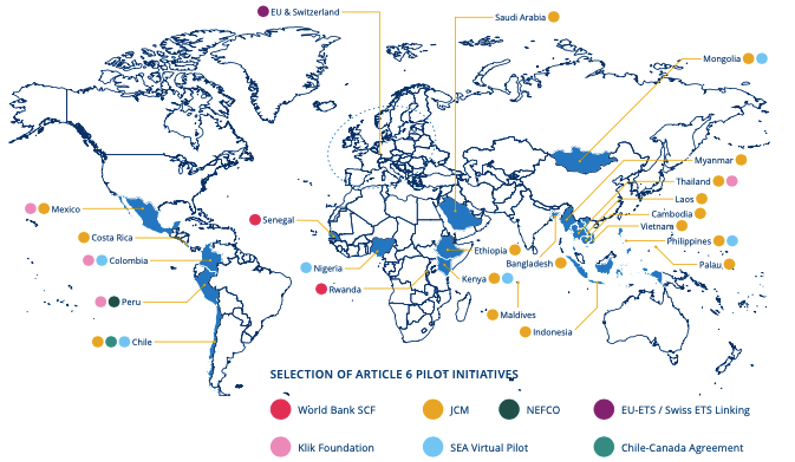

According to a study by Climate Focus, ten countries, including Canada, Japan and Chile and a number of international organizations, such as the World Bank, EBRD and Nefco are engaged in such international CO2 pilots.

Climate Focus: overview of CO2-pilots

These examples illustrate how two countries can achieve more ambitious CO2 targets using the CO2 market and international transfer of carbon credits. And companies that voluntarily offset their CO2 emissions through international CO2 projects contribute to achieving their CO2 target in those countries. These companies do this out of responsibility for their climate impact or because they want to sell climate-neutral projects or services. Companies that agree on the CO2 plans within the framework of the Science Based Targets may also use offsets in addition to their own reductions.

Future developments: EU Climate Law and EU ETS

In the future, the scope of CO2 obligations will increase and more sectors and companies will receive a CO2 tax from their government or fall under emissions trading. As a result, the reductions that are realized in another country will have to be transferred to contribute to the country in which that company is located (CA).

European Member States may in the future also make use of this opportunity. In November, Switzerland signed its second ITMO agreement with Ghana, and more are planned. Sweden is preparing CO2 deals with Ethiopia, Nepal, Cambodia. German Secretary of State for the Environment, Jochen Flasbarth, said at a meeting last month that Article 6 reductions could be on top of the EU’s 55 percent reduction. In the European Parliament, an amendment proposal for this from the European People’s Party has not yet achieved a majority. But the examples mentioned certainly deserve to be followed. The EU Council did agree on the European Climate Law again in December and said it would just follow international progress. Also, this approach can become part of the ETS Reviews that will be discussed Spring 2021.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.