Shades of REDD+

Reforming the International Financial Systems to Value High-Integrity Forests

19 October 2023 | Next week, the Republic of the Congo will host the Three Basins Summit of the Amazon – Congo – Borneo – Mekong – Southeast Asia tropical forest basins. These three basins account for 80 percent of the world’s tropical forests, which house two-thirds of terrestrial biodiversity and play an essential role in regulating the global carbon balance. Rarely has there been an event where forests play a more central role than the forthcoming meeting in Brazzaville. The Summit provides a unique opportunity to make the case for a reform of the rules of global public finance to value tropical forests as global climate and biodiversity assets.

The international financial system fails to recognize the value of tropical forest systems as global assets that are essential for a safe and healthy environment for all people. Countries located in the three basins are developing or emerging economies that face the challenge of combining conservation with development goals. These countries often depend on external finance – private and public – to invest in the institutions, capacities, policies, and infrastructure that are essential components of sustainable development. Such finance often demands investments in activities that promise stable and fast returns. As a result, the international financial system continues to favor short-term exploitation of land and resources over conservation and sustainable use to the detriment of our climate and ecosystems.

A reform that effectively supports vulnerable countries is overdue, and another crisis is looming.

The call for a reform of the multilateral financial system is spearheaded by Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados. In September 2022, Mottley issued a passionate warning that vulnerable developing countries were unable to meet the triple crisis of climate change, debt, and increased costs of living. Mottley left no doubt that the international financial system fails small island states that need greater liquidity to react quickly to climate-induced hurricanes and other catastrophic weather events. Multilateral finance organizations do not offer developing countries the tools to effectively respond to crises and invest in sustainable development and human, economic, and climate resilience. Small island states and other developing countries also need increased long-term finance to build climate-resilient economies. Mottley’s call for action resulted in the Bridgetown Initiative. This Initiative advocates for changes to the international finance system with the goal of increasing liquidity and access to resources for countries that suffer from an acceleration in the number and increase of severity of climate-induced disasters.

There is another urgent challenge for which the multilateral finance system needs to find an answer before it is too late. The world can only achieve climate and biodiversity goals if tropical forests are conserved. Protecting and maintaining them cannot be done by forest countries alone; instead, it is a global task that needs to be honored and supported through systems that recognize and value the essential ecosystem services that these forests deliver.

The international community is liable to help countries that face frequent destruction through catastrophic weather events. However, it is also liable to allow countries to pursue sustainable development without clearing their forests.

Global finance needs to be reformed and ‘grey’ finance needs to be ‘greened.’

It will be difficult to impossible to protect tropical forests if mainstream development finance is not reformed to account for climate action and nature conservation. The current multilateral finance architecture fails to value countries’ natural assets as global public goods. In the context of the UN climate and biodiversity regimes and the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” the international financial system must create development incentives linked to the conservation – not the consumption – of forests.

This can be done by adopting the calls by the Bridgetown Initiative with amendments to reflect the needs of countries that administer tropical forests. The following proposed amendments would benefit countries in all three tropical forest basins.

First, since the protection of tropical forests involves safeguarding essential global ecosystem services that all people depend on, multilateral development finance organizations should agree to assign a monetary value to these forests that factors in the roles forests play in stabilizing the global climate, regulating the water cycle, and providing biodiversity resources—among other services. Considering forests to be national (and, in fact, international) assets would drive mainstream financial organizations to invest in long-term conservation. Valuing the roles of forests in the long term could replace the short-term perspective of the current financial system that emphasizes exploitation with a system that incentivizes managing forests as essential government assets.

Efforts to value the forests of the Congo Basin are already underway and can provide important input to the proposed reform of public debt management systems. Proposed debt reforms call for the international financial system to account for the value of standing forests when establishing the debt limits of countries, their eligibility for finance, and the conditions under which they can access finance.

Second, public sector financing for forest countries — in particular those of the Congo Basin, which are often overlooked when it comes to allocating climate finance — needs to be scaled. This can be achieved by establishing a new funding window under the Resilience and Sustainability Trust administered by the International Monetary Fund. This funding window would provide vulnerable forest countries access to immediate and long-term financing in the face of the climate crisis. The funding window would make large-scale funds available for budget support and policy reform for forest countries to implement forest-friendly development strategies. Such a funding window could offer results-based payments in the form of grants to poorer countries that would be disbursed against the achievements of policy goals in addition to concessional loans with longer-term maturity and grace periods that enable countries to make investments into sustainable infrastructure and land use.

Action is particularly urgent in the Congo Basin

Multilateral finance organizations and other global financial institutions should value all high-integrity tropical forests. However, proper consideration of forests is particularly urgent in the Congo Basin, an expanse of 180 million hectares of forests that includes the world’s largest area of high-integrity forests. Although relatively undisturbed in historical terms compared to other tropical forests, the Congo Basin forests face severe risks. Deforestation in the region is increasing. In 2021, a total of 636,000 hectares were deforested across the six Congo Basin countries, amounting to nearly 10 percent of global deforestation.[1] This represents a 4.9 percent yearly increase in deforestation relative to the average annual deforestation in the Congo Basin in 2018-20 (606,000 ha/year).

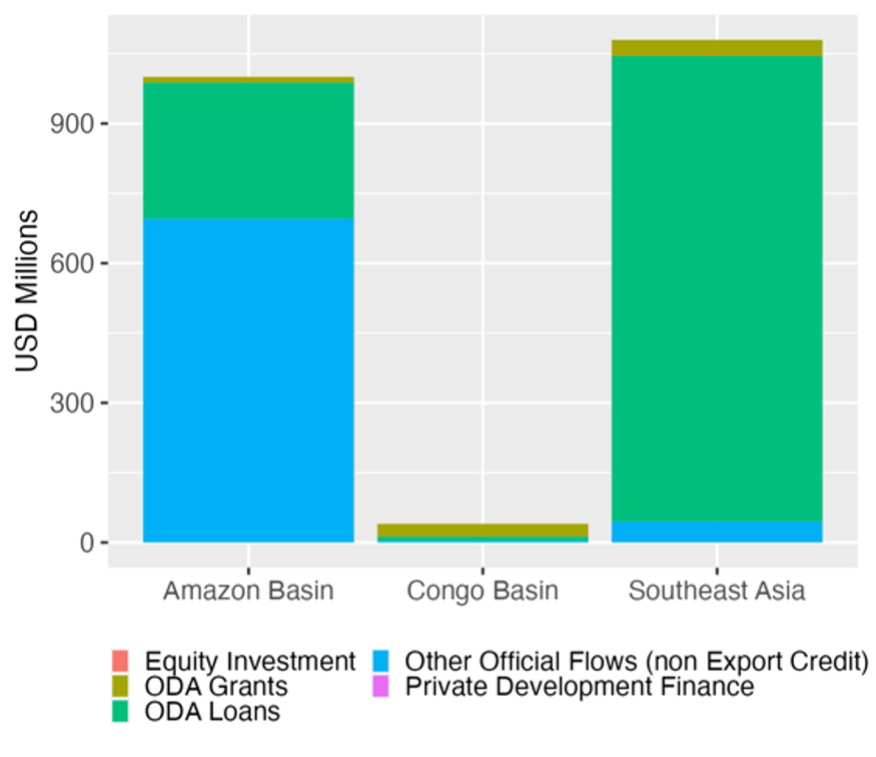

Today, the climate and forest finance received by the countries of the region Congo is neither commensurate to the finance needs of the region nor reflective of the ecosystem and climate services that the region provides. Despite hosting the second largest forest area worldwide, the finance for forest and environmental protection in the Congo Basin is just about 4 percent (USD 40 million between 2017 and 2021) of the amount received by the Amazon Basin and Southeast Asia (around USD 1 billion each) in the same period.

In sum, the international financial system must be reformed to increase liquidity for developing countries by reducing debt burdens, resourcing climate-resilient economies, providing budget support, and recognizing the economic value of ecosystem conservation. The goals of such reforms are to address shortcomings of the international financial system, which currently make it impossible for developing countries to respond to global climate, biodiversity, and economic challenges, and to ensure sustainable development and green growth. Policymakers convening in Brazzaville should take a deep breath and seriously consider the financial needs of the Congo Basin and other forest countries and design a new fiscal framework that must establish continued incentives to protect those forests that are essential for all of us.

Hero image photo credit: Valdhy Mbemba on Unsplash

[1] Forest Declaration Assessment Partners. (2022).

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.