How To Track Climate Legislation Around The World

One hundred and forty-four countries have ratified the Paris Climate Agreement, and 143 of them say they’ll stay in it – even if Donald Trump pulls the United States out. But staying in and delivering what you stayed in to do are two different things. One way to track progress is to track laws, and a newly-updated database makes it surprisingly easy – and fun – to do.

11 May 2017 | BONN | It’s not exactly “World of Warcraft”, but the newly-updated “Climate Change Laws of the World” data base is oddly addictive. The site, which is hosted jointly by the London School of Economics and Columbia University, it tracks more than 1,200 climate-change-related laws and 250 ongoing climate-related court cases in 164 countries worldwide.

If that doesn’t hook you, try “US Climate Change Litigation”, which is a sister site hosted by Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center to track environmental lawsuits in the United States.

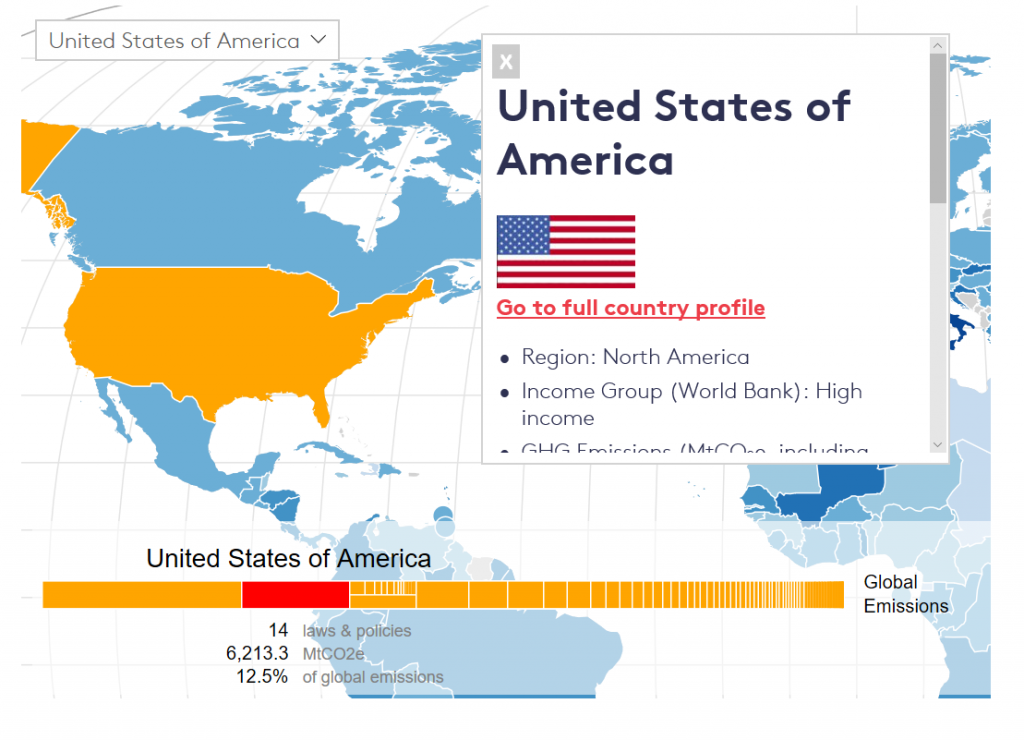

Poke around both sites, and you’ll learn that the United States has eight federal laws related to climate change and six climate policies; while hundreds of lawsuits are going on across the country – including 54 under the Clean Air Act alone. If you need some guidance, check out this summary of findings, which came out on May 9 at mid-year climate talks in Bonn, Germany.

Listen to the Podcast

For a deep dive into the findings, listen to the most recent episode of Bionic Planet, available through Bionic-Planet.com, iTunes, TuneIn, Stitcher, and pretty much wherever you access your potcasts.

Why Track Laws?

Countries won’t officially take stock of their progress under the Paris Agreement until 2023, when they sit down and see who did what – and how everyone can do more. That’s critical, because only by doing more can we prevent temperatures from rising more than 1.5°C (2.7°F).

At this point, however, we don’t even know exactly what activities countries will be taking stock of; the “stocktaking” effort is one of the things negotiators are negotiating this week and next in Bonn. So, we turn to proxies – like renewable-energy growth, rates of deforestation, and of course legal frameworks.

Sam Fankhauser, who co-directs the LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change, says there are clear linkages between a country’s Paris Climate Pledge, or “NDC” (Nationally-Determined Contribution) and its laws.

“The Paris Pledges – the NDCs – didn’t come out of nothing,” he says. “They weren’t made in a vacuum. They’re based on a lot of law-making at the domestic level.”

Where Next?

Unfortunately, he says, a deeper dive shows that only seven of the 20 leading industrialized countries (G-20) have laws that will ensure they meet their pledges, although 47 laws have been implemented since the Paris Agreement.

Developed countries have been passing fewer new pieces of legislation than they did in the past, but need to instead focus on strengthening existing laws and filling in gaps, he says.

“A lot of the G-20 countries are slowly taking steps to fill the gap between their NDCs…and their national legislative realities, but there’s much more to do,” Fankhauser says, noting that China, for instance, has incorporated its NDC into its 13th five-year plan.

For citizens living in a democracy, Fankhauser says: get active, because it works.

“Most democratic countries have a culture where laws are being passed using a process that involves public engagement,” he says. “NGOs and other stakeholders have an opportunity to give feedback and as politicians tend to like to be re-elected, they listen to what their voters think.”

Surprisingly – and encouragingly – poorer countries have also been stepping up with comprehensive legislation, especially for adapting to climate change.

“Climate change lawmaking truly is a global effort,” Fankhauser says. “There are countries of every economic, social, cultural description you can think of that are passing climate change laws.”

Low-income countries such as Malawi, Mali, Benin and several others are moving on climate in some capacity be it energy efficiency provisions or climate change legislation. Additionally, oil rich countries Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan and the United Arab Emirates have established policies that acknowledge a need for clean energy.

Not that there aren’t laggards, however, and the study reveals half a dozen countries lack any climate-related legislation.

“We need to focus on this gap,” says Martin Chungong, Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, a 130-year-old intergovernmental organization that helps legislators around the world learn from each other’s mistakes and develop policies that fit together, like a global jigsaw puzzle.

“You don’t want weak links in the chain because as (former UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon used to say, ‘climate change knows no boundaries,'” he adds.

Meanwhile, courts around the world are complementing the actions of legislators, ruling on the implementation of existing climate laws or providing a basis for the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions. Outside the United States, there have been over 250 court cases in which climate change is a relevant factor. Two-thirds of court cases have either strengthened or maintained climate change regulation. In one-third of cases, policies have been weakened. However, the evidence base on court cases is less complete than that on climate change legislation.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.