Stay The Course With Environmental Markets Benefitting Business And Rural Landowners

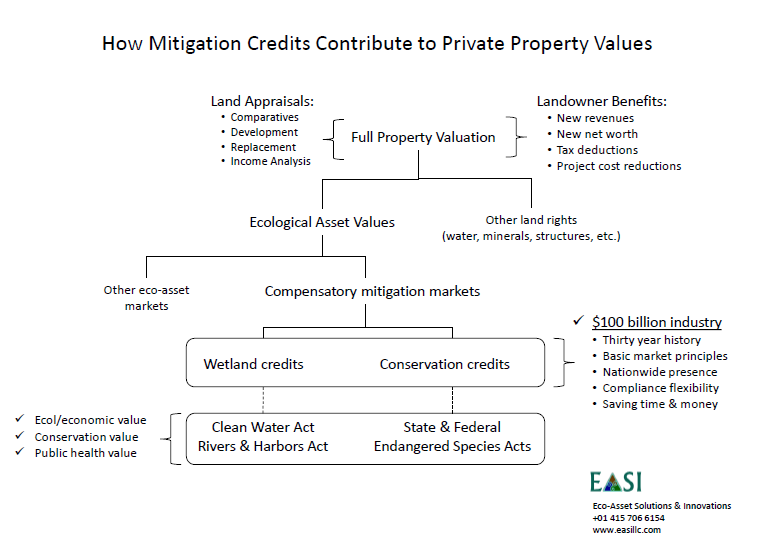

The 30 year old marketplace for ecological assets, recently valued at $100 billion, may be changing the face of real estate in the United States. A long-time market analyst says these changes fit perfectly with streamlined government programs catering to rural America, business and industry – constituencies poised to realize both revenue opportunities and higher property values derived from eco-assets.

29 November 2016 | Starting in the 1990s energy companies began unloading raw, undeveloped land they owned but no longer needed – a consequence of energy conservation efforts that reduced the need to build new power plants. Most companies either donated the unneeded land for preservation or recreation purposes – a seemingly smart public relations move – or sold the property at conventional land prices. The shrewd companies, however, gave thought to the land’s ecological value, meaning its ability to harbor rare species, preserve valuable wetlands, improve soil quality and more.

Consider as an example Allegheny Power Company, the Pennsylvania-based electric utility. In 2002, an IRS-approved appraisal of developable eco-assets basically doubled the market value of their Canaan Valley property located in West Virginia – from USD 17 million to $33 million. The company sold 12,000 acres to the non-profit Fish & Wildlife Foundation at the traditional land price ($17M), then claimed a tax deduction on the “gift” represented by the incremental $16 million eco-asset value identified by an appraiser. In addition to earning $17 million from the sale, Allegheny offset their next-year tax liability by $5.1 million. The company realized a total value of $22M on a property that had essentially no cost basis, having been purchased in the early 1900s.

What worked for industry then has also worked for farmers and ranchers in recent years. An eco-asset inventory of an underutilized 395-acre California horse ranch uncovered five rare species present on the property or living next door. This made the property highly desirable as a conservation bank – so much so that a nearby renewable energy company bought 290 of the 395 acres to help satisfy the company’s compensatory mitigation obligations. The negotiated sale price took into account the market value for species mitigation credits. The owner sold 290 acres of this property for $4,400 per acre as opposed to $1,300 per acre – nearly 3.5 times higher than nearby properties – based on the value of mitigation credits that could have been developed and taken to market.

These case studies demonstrate that landowners can leave money on the table if they don’t consider the market power of ecological assets in measuring a property’s true worth. Of course, not every property will be able to earn two or three times market from an eco-asset valuation, but nearly every rural property is capable of generating some level of ecological value, especially if the environmental marketplace continues to operate, expand and diversify as it has done since the 1980s.

An expanding environmental marketplace fits in perfectly with a streamlined government that caters to rural constituencies across the U.S. Rural America can benefit greatly by discovering the heretofore hidden ecological asset value of underutilized, undervalued farm and ranchland properties.

The Environmental Marketplace

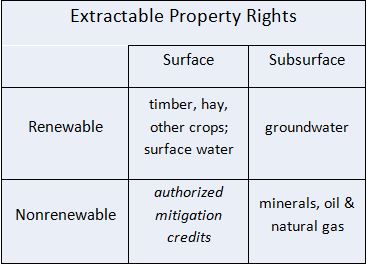

Ecological assets represent ‘units’ of goods & services produced in nature; they are an aspect of natural capital. Eco-assets such as compensatory mitigation credits are economic resources anchored in the land. They can be individually owned, developed and used just like more familiar mineral or water property rights. More specifically, mitigation credits can be characterized as extractable, nonrenewable surface rights. These rights are attached to properties that qualify for such credits under a variety of existing government programs. They are authorized by agencies such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the Environmental Protection Agency. Mitigation credits are considered nonrenewable because agency regulations mandate that mitigation credits can only be used once to offset or compensate for nearby development impacts. The credits are then reported as ‘withdrawn’ and permanently retired from the landowner account authorized by a state or federal agency.

By comparison, timber is an extractable, renewable surface right. Water is also an extractable, renewable resource, but this resource occurs as either a surface or subsurface right (groundwater) depending on the point of origin. On the other hand minerals, oil and gas are extractable, nonrenewable subsurface rights.

Mitigation credits represent a fourth unique type of property right, but in this case the ‘rights’ are attached to agency-authorized permissions developed under regulations of the Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act.

The credits trade hands between buyers and sellers for a mutually agreed upon market price, at which point they become bookable assets subject to the same accounting, auditing and taxation rules as other goods or services. They help measure the relative worth of certain ecosystem services, leading to lasting conservation of now-rare habitats whose market value contributes to regional economic productivity. This means that rights to extract ecological natural capital, measured as mitigation credits, now also exist as a benefit of land ownership. The value of these credits is realized as the assets (credits) are authorized, developed, inventoried and taken to market. At that point they are subject to the same market forces that shape price and liquidity for other commodities including principles of supply, demand, and willingness-to-pay.

The Table Setters: Reagan, Bush, Hayek and Keynes

The variety of ecological assets has grown in tandem with their volume from the late 1980s when the first mitigation credits were approved during the Ronald Reagan-George Bush Senior years. Agencies have learned that measured improvements in air and water quality, waste and water management, and biodiversity protection can be realized by implementing reward-based, marketplace programs instead of relying only on penalty-based measures to meet the nation’s environmental quality goals.

These markets have led to quality of life improvements without policymakers needing to pass new laws. Incentive-based compliance programs (environmental markets) save money for business and industry, help meet resource management goals, and at the same time boost the value of real property to reflect embedded natural capital.

Mitigation credit markets are a little bit of John Hayek, a little bit of Maynard Keynes when looked at in the language of that long-standing economic debate. The credits are an expression of free markets at work inside a framework of agency guidelines designed to protect the public interest. The foundation for these programs was laid during George Bush Sr.’s administration when “no net loss” of wetland habitat became the mantra necessary to protect a rapidly disappearing natural resource. Every administration since has adopted the no net loss approach. It has been applied to other rare types of habitat – grasslands, woodlands, scrub-shrub lands – especially in Texas and other western states where the lure of markets and no net loss goals have converged with surprising fiscal appeal.

In Texas, mitigation credits are now worth over $1.5 billion in commodity value, according to research by Eco-Asset Solutions & Innovations (EASI), a firm focused on natural capital markets values. These credits have protected over 75,000 acres of land (per US Army Corps of Engineers data) that was previously underutilized, therefore undervalued, in terms of conservation markets. The Texas mitigation economy is so strong, in fact, that landowners have been seeking new ways to transform these previously hidden land values into revenues.

Undervalued No More

This is not a soft marketplace, as it turns out. A 2015 analysis by EASI valued authorized mitigation credits at more than $100 billion nationwide with something like $1-2 billion in transactions occurring each year. Their assessment was based on a unique, in-depth study of mitigation credit price records EASI has gathered from every part of the US.

There is a growing belief that these assets have the ability to reshape our understanding of the fundamental value of real estate based on appraisal methods that build on the recently aggregated mitigation credit market data. The Allegheny Power case study, for example, drew on the expertise of Kauttu Valuation, an appraisal firm based in Saint Augustine, Florida. More recently, Appraisal Institute has been exploring these methods, including the Northern California chapter that sponsored a day-long seminar about environmental markets, ecological assets and mitigation credit valuation. The seminar presented a standard approach to assessing ecological assets that can be immediately useful not only in California, but in Texas, Wisconsin, Ohio, North Carolina, Florida and other states that have a long track record of market-based compensatory mitigation programs.

Federal Agencies Should Stay the Course

Nothing sheds light on value more quickly than direct market price signals. Nothing could be more meaningful to the private sector than to discover the heretofore hidden value of underutilized rural lands.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s EnviroAtlas is a good example of an agency-sponsored tool that has contributed smartly to environmental market infrastructure. Specifically, the environmental markets data layer has been developed in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This tool offers the general public (business and industry included) access to information supporting new markets such as water quality trading, another form of compensatory mitigation.

Farm Bill legislation can likewise continue to build out environmental market programs developed by the USDA Office of Environmental Markets and implemented via the Natural Resource Conservation Service’s environmental markets program as well as the Forest Service’s program to monetize ecosystem services. USDA has made unequivocal commitments to inform and advise rural landowners about compensatory mitigation market opportunities.

So has the US Army. The Army Corps of Engineers is responsible under law for managing the nation’s wetlands mitigation program. The Corps has subsequently developed the largest and most detailed database supporting compensatory mitigation credit markets. Their RIBITS website has tracked and accounted for wetland mitigation credits for the past few decades. More recently, RIBITS has incorporated Fish & Wildlife Service conservation banking data. The Corps has also been in talks to integrate EPA-USDA water quality trading data into RIBITS. This suggests a future one-stop-shop for landowners, industry and other mitigation credit market participants, something that would be a huge advance for the environmental marketplace overall.

Given the opportunities evident in these developing markets, and the scope of agency programs supporting private sector interests, decision-makers may wish to consider the following steps that could improve mitigation credit marketplace efficiencies and participation.

- Update RIBITS so mitigation credit data is current, complete and comprehensive. RIBITS data can be out of date, or the information presented online can be inconsistent with downloadable data sets. This can confuse users who need to make land development or investment decisions based on accurate market patterns and trends. Despite these needs, RIBITS should continue to serve as the centralized national dataset accommodating all compensatory mitigation credit activity, including water quality trading data as well as future soil or biomass carbon sequestration data.

- Represent mitigation credit prices and volume to market participants. The mitigation credit marketplace suffers from lack of transparency (high opacity) and resulting high price volatility. This is because mitigation credit sellers have protected price data in an effort to avoid being undersold by competitors. Further, sellers have been relatively few so the availability of credits has not been widely known to buyers. This means buyers cannot easily find what they need to comply with permit obligations. Nor can buyers predict a reasonable price for the credits they are required to purchase. This has made market transaction costs unnecessarily high. But publically available price data has been aggregated, and mitigation credit availability can be reported in transparent ways – especially if RIBITS data is updated and effectively maintained. Now is the time to present this information in user-friendly ways.

- Freely release the results of government bid requests for mitigation. Government entities such as transportation departments often announce Requests for Bids in advance of projects requiring compensatory mitigation. These bid requests are part of the public record. But the results of the bidding process are not made public because sellers want to protect their pricing strategies. S. Department of Transportation, for example, will not release bid results without a Freedom of Information request. These extra steps discourage market efficiency and extend the plight of disadvantaged mitigation credit buyers. Bid results should be made public as a way to improve market participation and efficiency.

- Expand conservation credit markets to include candidate species under the Endangered Species Act. Current conservation banking programs focus on wildlife and plant species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act or state equivalents. Expanding compensatory mitigation programs to include candidate species would accomplish several things. This would:

- Reduce the risk of candidate species being listed as threatened or endangered in the future

- Encourage market-based conservation of habitat and related ecosystem services

- Recruit more states to participate in conservation banking programs, making the conservation credit market segment more robust nationally.

- Provide for investment in and resale of unused, banked mitigation credits. Agencies have discouraged the resale of unused mitigation credits in order to minimize commodity accounting burdens. In some cases this leads to stranded investments for credit buyers. For example, a buyer can purchase a number of credits to offset unavoidable project impacts, only to later learn that fewer credits than expected were needed to satisfy compliance obligations. This leaves the buyer with leftover credits. If unused credits cannot be resold the buyer is left with a stranded investment. Agencies should encourage secondary markets for unused mitigation credits as a way to ensure the liquidity of these ecological assets.

- Provide for public-private development partnerships within or adjacent to federal lands. Rehabilitation of forested landscapes is increasingly important to natural resource managers. Catastrophic fires – the result of past management practices, insect infestations and drought – have seriously compromised ecological productivity in large portions of the U.S. Soil, water and biodiversity resources can be severely degraded in these areas meaning that ecological and economic productivity can be compromised for decades. Recovery efforts are complicated by artificial boundaries that segregate public vs. private lands when watersheds and species often range across such boundaries. This suggests that special public-private partnerships are necessary to adequately address this challenge. S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management in particular should study incentive-based rehabilitation strategies that simultaneously benefit both public and private lands in areas at risk for rapid depletion of ecosystem services.

- Continue to widely educate potential market participants, especially landowners, about the rationale, mechanics and prospective value of compensatory mitigation projects. Farmers & ranchers, business & industry are still largely unaware of the economic opportunities represented by mitigation programs. Ranchers, for example, are often suspicious of government-sponsored projects and have in many cases dismissed these opportunities. Industry is still largely unaware that significant economic value can be found on underutilized land. Investors are actively discouraged from participating in mitigation credit markets due to agency-imposed constraints. The net effect has been to constrict growth of the marketplace despite its having achieved the $100 billion milestone. Agencies should commit to a persistent, widespread effort to build market participation in order to achieve the next $100 billion in value. Not only will this help validate the environmental marketplace to the benefit of private sector interests, it will facilitate highly valued quality-of-life outcomes on private lands.

William Coleman has 40 years’ experience in environmental and sustainability management, specializing in ecological asset development and market management for agri-business and energy companies. He is currently managing his consulting firm, Eco-Asset Solutions & Innovations in the San Francisco area. He can be reached at wcoleman@easillc.com.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.