The Trillion-Dollar Deforestation Time Bomb And How To Defuse It

Two new reports show that global corporations are both victims and perpetrators of deforestation. One report shows they could lose nearly $1 trillion per year if current trends continue. The other shows that nearly 60% of the roughly 250 companies most responsible for deforestation have no viable strategy for fixing the problem.

5 December 2016 | You probably recognize many of the companies on the first of the two lists we’ll be examining today – like Colgate Palmolive, L’Oréal, and McDonald’s, which are household names. You might not know the others – like Marfrig Global Foods and Bunge – but they’re equally massive, and they depend on sustainable supplies of palm, soy, cattle, and timber & pulp – the “big four” forest risk commodities responsible most of the world’s deforestation. These four commodities account for 24% of the cumulative income of 187 companies surveyed for a new report called “Revenue at risk: Why addressing deforestation is critical to business success”, and their supplies could be disrupted if deforestation continues.

Produced by CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) at the behest of 365 institutional investors, the report concludes that disruptions in supplies of forest risk commodities could cost $906 billion per year.

There’s another list, too: the Forest 500, which names and shames the 500 entities that can end deforestation. Half those entities are companies, and many of them have pledged to end practices that kill forests. The list is compiled by the Global Canopy Programme (GCP), which ranks those pledges and gives credit for good ones. GCP also published a report today, and it’s called “Sleeping giants of deforestation”.

It shows that 57% of the companies on the Forest 500 either have no policies to end deforestation or none that the organization deems credible, while the CDP report shows that just 42% of the companies on the risk side have even bothered to investigate the ways that supply disruptions could impact their business.

On top of that, the Forest Trends Supply Change project tracks the progress that companies are reporting on their deforestation pledges and shows less than half of them are even reporting progress.

Add the findings up, and you find a global agriculture sector facing an existential threat and partially acting on it, but mostly hobbled by poor traceability and weak governance or blinded by apathy and overconfidence and frustrated by shortages of certified raw materials.

The GCP report looked at countries, too, and found many of those on the supply side – the rainforest countries that export forest risk commodities – were beginning to take action, while those on the demand side – the developed countries that import them – aren’t. Paradoxically, while developed countries often funded sustainability efforts in tropical countries, only two of the importing countries on the Forest 500 – Germany and the Netherlands – formally support national sustainability efforts among consumers.

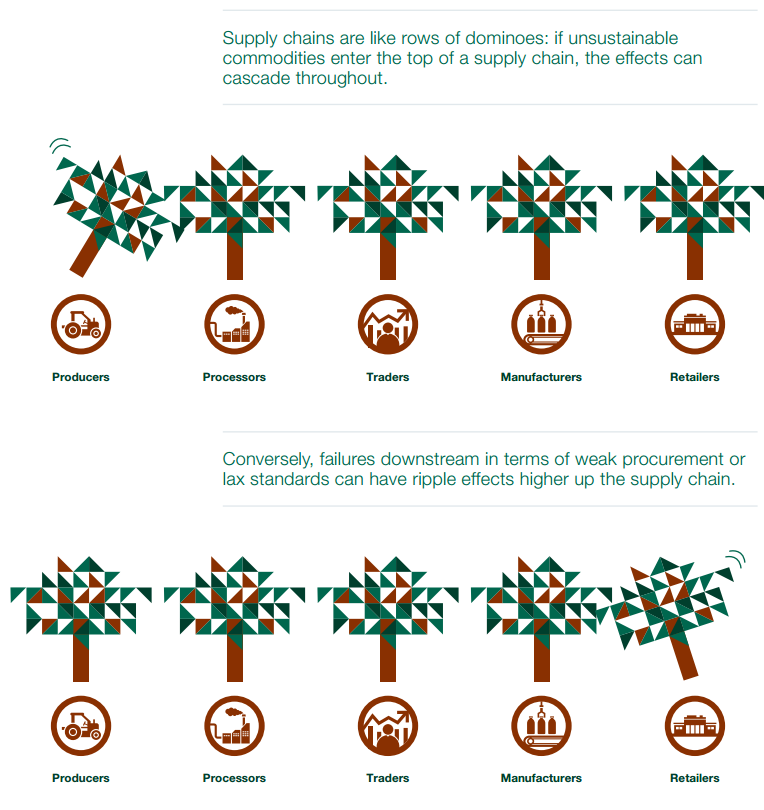

One Thing Leads to Another

The Bright(ish) Side

It’s not all doom and gloom.

Supply Change also found that those pledges with publicly-available disclosure were, on average, more than 70% of the way towards completion; and while many companies are certainly avoiding disclosure to hide bad performance, others have taken productive actions that are just difficult to quantify.

Danone, for example, is helping small farmers around the world shift to sustainable farming, and progress on that front won’t show up incrementally the way shifting to certified commodities does. Likewise, Norwegian consumer goods group Orkla implemented a three-pronged sustainable palm oil policy in 2014 and recently saw their Forest 500 rating jump from three stars to five, as did two other companies: Colgate Palmolive and Marks & Spencer.

Orkla has been working for years to replace palm oil with options that are healthier and not associated with deforestation, and their 2014 reforms involved renegotiating contracts with key suppliers and becoming a member of the RSPO at Group level.

“We have a regular dialogue with suppliers about the progress of the work,” says Ellen Behrens, the company’s Vice President for Corporate Responsibility. “We only work with suppliers who have good plans for sustainable improvement. Examples of supplier activities include the use of satellite-based risk assessments, fire alert systems and various types of training programs.”

Like Danone, they’re also looking to drive complex changes on the ground.

“We look for suppliers who engage in training of mill management and of farmers, and who engage in awareness-building in local communities,” she says.

The final component, she says, is certification, which among others is important to monitor compliance with important aspects such as working conditions and the use of pesticides. Their most recent disclosure document shows that 40% of the palm oil, blends, and derivatives they purchase are either certified as sustainable by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) or have their impacts offset by Green Palm certificates.

“Certification is the easiest activity to communicate in a quantified way,” says Behrens. “We’re currently looking into how to verify other activities.”

That’s something to keep in mind as you explore the group’s Supply Change profile, and especially it’s palm section: companies whose only pledge involves certification will show more “quantitative progress” than those undertaking more complex strategies, so it pays to heed the milestones embedded in the profile as well.

Radical Transparency

The reports come in as a flurry of new transparency tools are also coming on line, as we covered in a recent edition of the Bionic Planet podcast, which is available on iTunes, TuneIn, Stitcher, and here:

Perils and Possibility

The CDP report uncovered a disturbing sense of confidence among companies with high exposure to the big four commodities, with 72% of them expressing confidence in their ability to source them in the future – even as 81% of companies in the Agricultural Production sector reported impacts related to forest-risk commodities in the past five years.

On the other hand, many also seemed unaware of the potential for growth that a shift to sustainable sourcing could offer.

“Investors are poised to capitalize on the opportunities that await,” wrote CDP CEO Paul Simpson in the foreword. “Some of the biggest index providers in the world, including S&P and STOXX, have created low-carbon indices to help investors direct their money towards the sustainable companies of the future. Investors see opportunities in sustainably managed timberland, and are beginning to direct funding to innovative approaches to protect forests, such as REDD+ credits.”

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.