How The Restoration Economy Can Help Us Withstand The Next Hurricane Harvey

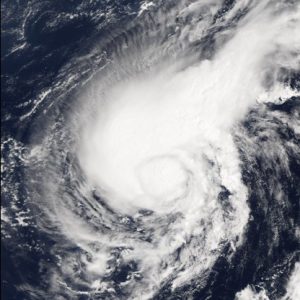

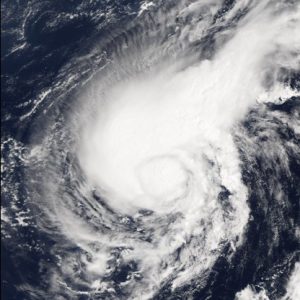

Hurricane Harvey reminded us just how vulnerable low-lying cities like Houston are in a climate-changed world – especially when we degrade the living ecosystems that regulate floods and absorb greenhouse gasses. Fortunately, we have plenty of tools we can use to develop the “green infrastructure” needed to help us navigate the new reality of life in the Anthropocene.

30 August 2017 | Three hundred miles north of hurricane-ravaged Houston, Rick Wilson is helping Dallas-Fort Worth grow in ways that don’t disrupt the natural systems that regulate floods. In so doing, he’s also paying off the mortgage on his ranch and paving the way for us all to better survive the next Hurricane Harvey.

Specifically, he’s earning money by restoring and maintaining the river that runs across his property, with the money coming from urban developers who are impacting other parts of the river.

That makes him part of the $25 billion “restoration economy” that pays more than 220,000 people across the United States to plant trees, fix swamps, and restore meadows that filter water, regulate floods, and absorb carbon dioxide.

It’s an economy that the city of Hoboken, New Jersey, joined after Hurricane Sandy pounded it in 2012. In response, Hoboken started restoring marshes and turning vacant land into a “resiliency park” that will mop up at least one million gallons of floodwater. Denver’s part of it as well; the city is funneling some of its water utility fees into forests that store and filter water. And, of course there’s California, where meadows and streams are legally recognized as “green” (as opposed to gray) infrastructure.

But what about Houston? After all, the city has endured six “storms of the century” in less than 30 years, and a 2015 study by the Harris County Flood Control District found that every acre of restored prairie absorbs the runoff from two acres of single-family homes. Surely the city is also restoring its wetlands or otherwise adding green infrastructure to its gray mix, right?

Not according to a scathing series of articles that ProPublica and the Texas Tribune published last year.

“As millions have flocked to the metropolitan area in recent decades, local officials have largely snubbed stricter building regulations, allowing developers to pave over crucial acres of prairie land that once absorbed huge amounts of rainwater,” the authors write. “That has led to an excess of floodwater during storms that chokes the city’s vast bayou network, drainage systems and two huge federally owned reservoirs, endangering many nearby homes.”

The series was especially hard on Mike Talbott, who ran the Harris County Flood Control District until last August. An engineer by training, he dismissed his own agency’s green infrastructure findings as “preliminary”, and he’s quoted as saying the idea that “these magic sponges out in the prairie would have absorbed all that water [from earlier floods] is absurd.”

To be fair, nothing could absorb all of the water from an event like Hurricane Harvey, but Talbott also dismissed efforts to incorporate climate change into future planning, arguing that climate scientists and conservationists had lost the plot.

“Their agenda to protect the environment overrides common sense,” he’s quoted as saying – and he’s hardly alone.

President Donald Trump recently dissolved a federal advisory panel on climate change, and his proposed budget slashes both climate research and adaptation – even as the costs of dealing with extreme weather are spiraling upwards by hundreds of billions of dollars.

On the other hand, dozens of other coastal cities are at least experimenting with green infrastructure, and 36 mayors from both major parties last year called for increased funding into hybrid gray/green infrastructure programs to protect them from rising tides.

“We need either the state – which doesn’t want to get involved because the governor doesn’t believe in sea-level rise – or the federal government to come up with funds,” said James C. Cason, the Republican Mayor of Coral Gables, Florida.

Hoboken Mayor Dawn Zimmer agreed – and identified the private sector as a source of funding.

“As people come through our redevelopment process, we require them to consider green infrastructure,” she said. “But we’re also looking at ways that we can incentivize it.”

Philadelphia incentivizes it by charging sewage fees based on a ratio of absorbent to non-absorbent ground cover, and Rick Wilson – the Texas rancher we met in the first paragraph – had an incentive to restore his stream as well. It came from a man named Adam Riggsbee, who is a “mitigation banker”.

That means Riggsbee makes his living restoring degraded meadows, swamps, and forests in order to generate environmental credits that he can sell to developers. It’s a system that balances environmental protection with economic development by leaving provisions for polluters or developers to do some damage if they do more good. The credits are sold through environmental markets, and an Ecosystem Marketplace study found at least $2.8 billion flows through these markets every year in the United States.

That money buys resilience, which is the ability to bounce back from adversity. It’s an ability we’ll need a lot of in the climate-changed decades ahead, and it doesn’t come cheap – but its cost pales in comparison to the cost of ignoring the challenge and just hoping it goes away.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.