Forests And Water: The Unappreciated Link

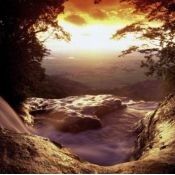

Science tells us that healthy forests make healthy rivers and lakes, but policy rarely reflects the connection. That could be changing as the general public comes to better understand the role that deforestation plays in climate change; an understanding that could ratchet up an appreciation of all the ecosystem services that forests deliver.

5 March 2015 | You think that a country blessed with 12 % of the world’s freshwater would be immune to droughts. The people of Sao Paulo certainly thought so until the Brazilian megacity went dry, leaving residents without water often for days.

Scientists tell us the drought happened because the country has demolished much of its natural infrastructure: the nearby forests and wetlands that sponge up rainwater for the city dry periods, and the far-away forests of the Amazon basin that have, in the past, provided humidity to fuel rains closer to home.

It’s a serious situation and one that has been receiving a lot of international attention. And, because of the clear connection between environmental degradation and worsened conditions, Sao Paulo’s drought has also spurred talk about the connection between forests and water.

This connection is hardly new. Conferences are held annually and committees are formed to address it, and cities from Denver in the United States to Heredia in Costa Rica and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania have all taken steps to secure their drinking water by shoring up their forests.

But despite these isolated efforts, a big gap exists between the recognized role of forests in hydrological cycles and national and international policies, says Thomas Hofer of the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Forestry Department and also a leader in the Mountains and Watersheds program.

Think Big

The policy gap coincides with a knowledge gap regarding forests and water. Sao Paulo’s drought is making it easy to see that water requires trees but it’s difficult to measure and quantify the process that produces a healthy supply of water. But attempting to figure out that precise calculation is part of the problem, Hofer says.

“We shouldn’t just talk about the understanding of the relationship between trees and water quality or quantity,” he says. There’s an intricate link between forests and water that encompasses many water-related process like soil stabilization, landslides and mud flows along with water security.

“It’s not just water, but the water cycle,” Hofer says. “And it’s not just forests, but the whole mosaic of land-use in a geographic region.”

It’s a suggestion to apply the landscape approach, which seeks to manage Earth’s ecosystems holistically rather than in sectors, to water management and policy. Landscape thinking has been growing steadily in the environmental space especially after considering how deforestation in the Amazon can have an impact on a city hundreds of miles away.

“It calls for a broad view of looking at the landscape mosaic,” says Kerry Cesareo, a Senior Director of forests at WWF, referring to deforestation in the Amazon. “And it calls for appropriate land-use over fairly large areas because actions happening far away can have an effect.”

But before the landscape approach can be translated into policy, both Cesareo and Hofer note the science backing it has to be available. So the knowledge gap must be filled.

Help Water by Saving Forests

As mentioned, there are ongoing activities addressing this knowledge gap. For example, the International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO), a non-governmental network on forest science, created a task force identifying forest and water connections through case studies. There is also a planned two day water and forest dialogue at this year’s World Forestry Congress, Hofer says, where the FAO plans to launch its international water and forest action plan.

There are other initiatives happening closer to the mainstream that will help close the information gap as well as bring attention to forest and water connections. One of those is the many zero-deforestation pledges companies, governments and other entities have committed to. Last year’s pledges ranged from the Consumer Goods Forum’s resolution to achieve zero net deforestation by 2020 to forested nations committing to slash forest loss under the Rio Branco Declaration.

“The pledges are a rallying cry around halting deforestation and environmental degradation,” says Cesareo.

The focus of these pledges has typically been climate related as standing trees help slow global warming. There hasn’t been too much attention paid to the water and biodiversity benefits to be gained by more standing forests. But it’s likely, Cesareo says, that the deforestation commitments will lead to more comprehensive land-use and conservation management-thus impacting water.

They are part of the process, Hofer says. “Zero deforestation pledges are one tool in a policy and action framework to secure world water resources,” he says.

The little mention of water regarding the deforestation pledges also doesn’t mean the companies and others making the commitments aren’t aware of these co-benefits and taking them into consideration.

“Increasingly, businesses and communities are recognizing the critical importance of preserving and protecting water supplies,” says Diane Holdorf, the Chief Sustainability Officer at the Kellogg Company, a major food production corporation. “Through sustainability commitments to reduce water use and through our work with peer companies at Consumer Goods Forum to achieve zero net deforestation, we will continue to prioritize water resource constraints.”

Interlinked Solutions for Interlinked Challenges

The zero deforestation pledges are an encouraging sign for the entire environmental sector although time will tell their true impact. If successful, the pledges will likely demonstrate that standing forests deliver healthy supplies of water contributing to the needed policy change regarding forest and water management.

Interlinked management of forest and water is already happening at different levels in both the public and private sector. Hofer sees significant value in merging the government ministries of forest and water together and there are a number of nations doing this. For instance, Turkey has combined the two. Other countries have taken it a step further. Namibia combines agriculture, forestry and water and Madagascar has a Ministry of Environment, Forest, Water and Tourism.

As for the private sector, Cesareo notes a success story in South Africa where portions of poorly managed forestry operations were restored into thriving natural areas with particular benefit to the Lake St. Lucia estuary, which is a part of South Africa’s iSimangaliso Wetland Park-the last remaining coastal wilderness in the country.

Mondi, the paper and packaging company, uses a landscape approach to manage its section of the ecosystem and as a result, not only delivers regular flows of freshwater into Lake St. Lucia but supports local communities and a wide range of wildlife.

There are other well documented cases-such as the aforementioned efforts in Colorado, Tanzania and Costa Rica. And, of course, there is Sao Paulo.

While there isn’t really a bright side to the city’s drought or other natural disasters, it does often shed light on critical issues that require addressing. It provides the mainstream awareness, Hofer says, that, along with scientific understanding, can deliver needed policy change.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.