As 2020 Deadline Looms, Companies Must Step Up To Meet Deforestation Commitments

All around the world, farmers are accelerating climate change by chopping trees to meet our ravenous appetite for palm oil, soy, and other commodities. At the same time, scores of companies have made hundreds of commitments designed to end that, and almost 60% of those commitments have a deadline of 2020 or earlier.

First in a continuing series

15 September 2016 | In 2009, Paul Polman took the helm at Unilever PLC – an Anglo-Dutch consumer-goods giant that gathers raw materials like palm oil, soybeans, and milk from hundreds of thousands of farms around the world and turns them into soaps and soups and other creations as diverse as Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, Hellmann’s mayonnaise, and Axe body wash.

Unfortunately, many of the farmers that feed the combine are chopping forests to do so, and that destroys habitat for endangered species, contaminates rivers and lakes, disrupts indigenous culture, and accelerates climate change. So Polman, in one of his first official acts as CEO, stopped using quarterly earnings to drive strategy and shifted instead to the nebulous concept of long-term “sustainability”.

Some shareholders bailed, and the stock plunged 8%, but Polman held firm, and one year later, his nebulous concept had crystallized into the company’s new Sustainable Living initiative: a clear, concrete, and verifiable 50-step process for completely restructuring the company’s supply chain from 2010 to 2020.

The company started working with environmental NGOs like WWF and suppliers like Archer Daniels Midland to help farmers across the United States and Brazil get more soybeans from the same patch of land, which takes the pressure off of nearby forests, while also pushing global certification initiatives to become more rigorous. They’re now implementing similar processes in different commodities around the world, and if all goes according to plan, the initiative will culminate in 2020 with 100% of Unilever’s raw materials coming from sustainable sources that don’t drive deforestation.

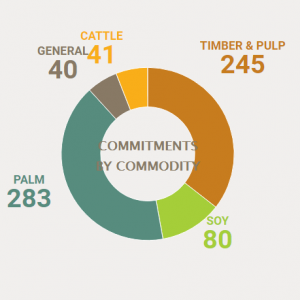

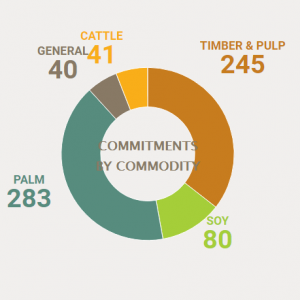

Five years after launching the program, Unilever is halfway to its goal, as noted by the Forest Trends Supply Change project, which tracks the progress that companies report on their commitments to improve sourcing of the “big four” drivers of deforestation: palm, soy, cattle, and timber & pulp.

Meanwhile, scores of companies have made similar pledges in the last two years, and roughly a quarter of those pledges have a target date of 2020 – meaning that relative newcomers are aiming to achieve in a shortened timeline what the early movers are taking a decade to do.

“This raises a lot of questions,” says Supply Change Senior Associate Ben McCarthy. “Are they biting off more than they can chew? Are they cutting corners to meet their goals? Or does the second-mover advantage mean they’ll actually pull it off?”

Story continues below

Countdown to 2020

Not all commitments are created equal, and many companies have more than one. Procter&Gamble, for example, has a 2020 target for its palm commitment, but a 2015 target for timber (which it met).

Supply Change has identified a total of 689 individual commitments, and 406 of them have a target date of 2020 or earlier. Some of those target dates have already passed; and of these, some have been met, others have been partially met, and still others have quietly been ignored.

One-hundred and sixty-four commitments have a target date of 2020 – the most popular year, even for new commitments. Indeed, of 141 new pledges identified by Supply Change in 2015, 35 of them have a target date of 2020, as do 11 of the 52 pledges made so far this year.

McCarthy’s analysis shows a disturbing counter-trend as well: while roughly a quarter of newer pledges have a target date of 2020, a growing number – roughly one-third of those made in the last two years – have no target date at all. Daniel Zarin, Director of Programs at the Climate and Land Use Alliance, says targets without dates amount to mere “aspiration” instead of “policy”.

“Aspiration is nice, but if they’re serious, the aspirational honeymoon should itself be time-bound,” he says. “Six to twelve months after announcing an aspiration, a company ought to have a time-bound execution plan; otherwise, we shouldn’t take them seriously.”

Deadlines and Milestones

Stephen Donofrio, a Senior Advisor to Supply Change, sees evidence that some of those aspirational goals are coalescing into policy – but not necessarily into time-bound commitments, at least not yet.

“Some companies with open-ended commitments are actually publishing clear milestones – like having full traceability to their suppliers by a date such as 2018 – and that’s good,” he says. “It’s not as good as a time-bound commitment, but they’re leery of making time-bound, high-profile commitments until they know what they can do, and it looks like they’re making serious efforts.”

Unfortunately, Supply Change data also shows a high correlation between undated targets and low disclosure: specifically, companies are only disclosing progress on 32% of the commitments that don’t have a target date, while they’re disclosing progress on 51% of the time-bound commitments, for an overall average of 44% – a figure that Donofrio says is way too low. He urges more companies to disclose progress, even if they’re falling short of expectations.

“This is difficult stuff, but from an investor risk perception, if a company offers zero information, then the investor may assume the worst,” he says. “If the company report says, ‘Hey we’re not totally on track to meeting our goals, and here are the challenges,’ then they’re demonstrating an ability to manage risk, which shareholders want to see.”

Several companies have set aggressive targets and won high marks for disclosing progress, regardless of results. US-based Kellogg’s, for example, is an early mover that set an aggressive target of sourcing all of its palm oil sustainably and making sure it’s fully traceable by 2015. By the end of 2014, the company had made tremendous progress but was “only” 73% of the way towards its goal, fully disclosed its progress.

“I’d also like to see more time-bound commitments and much more disclosure – especially when companies are facing challenges – but if you push that too strongly, you might discourage companies from setting targets at all,” he adds. “The first movers – by taking the plunge and getting out in front – are now steps ahead of the pack in achieving their commitments, but the good news for those in the middle and the laggards is that, through collaborative initiatives such as the Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 and the Consumer Goods Forum, they have an opportunity to learn from these leaders.”

Interestingly, those collaborative efforts are partly responsible for the preponderance of 2020 target dates.

Why 2020? And Why so Many Newcomers?

While Unilever and Kellogg’s were setting their early goals, the Consumer Goods Forum was setting a 2020 zero net deforestation resolution for its members, and Switzerland’s Nestlé committed to zero deforestation before Unilever did, also with a 2020 target, while the UK’s Marks & Spencer soon followed, also aiming for 2020.

In 2012, the Rio Earth Summit – known as “Rio+20” – spawned the Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 to support the CGF’s mission, but things didn’t get rolling until 2014, when scores of companies endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF), which is a global pledge to, among other things, “meet the private-sector goal of eliminating deforestation from the production of agricultural commodities such as palm oil, soy, paper, and beef products by no later than 2020.”

Suddenly, other food giants like Japan’s Kao and Norway’s Orkla were also pledging to remove deforestation from their supply chains by 2020

“It’s a round number, and it’s achievable, with a few exceptions,” says Zarin. “And it’s tied to the implementation calendar for the Paris agreement, which could well be accelerated.”

And it might also be good for business – or at least not bad. Unilever’s share price has risen steadily with the S&P 500 since its 2009 low, and it shows no signs of faltering.

Next in this Series: While most companies that disclose their results are showing good progress, most companies aren’t disclosing.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.